Anne Speckhard & Sophia AbiNajm Download PDF Introduction Targeted violence and violent extremism are on…

Facebook and Pro-ISIS Kurdish Content: Denying the Extremist Group a Key Platform

By Mohammed A. Salih*

The dramatic rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in the mid-2010s not only captured the attention of the world with its violent activities and swift territorial gains but also its extensive online presence and propaganda activities. Positioning itself as a state, ISIS established a sophisticated propaganda apparatus incorporating materials produced directly by its media houses, such as al-Furqan, al-Hayat, and provincial teams. In parallel with this, an army of members, supporters, and fans launched into action on the Internet and social media platforms, creating a vast network of activity and disseminating the group’s messages in the online sphere. The group’s material success on the ground and its rapidly spreading propaganda online complemented each other and drew thousands to the ISIS cause from around the world. This mandated a swift and decisive response, bringing together governments, tech companies, and myriads of experts in a concerted effort to technically restrict the group’s online presence and understand and counter the content of its messages.

Though the territorial defeat of ISIS and the capture of thousands of its fighters have significantly reduced its combat capabilities, the group continues to maintain a formidable militant presence in Syria and parts of Iraq. The U.S. Central Command has recently cautioned that the group is actively attempting to reconstitute its forces in these regions. . In parallel with this, and despite its territorial defeat, ISIS continues its global propaganda and recruitment efforts through the internet. An important community that ISIS has, over the years, sought to target through its propaganda is Kurds, a 30 to 40-million-strong people scattered over the states of Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

As a mainly Sunni Muslim community politically disadvantaged and persecuted in most of the region, Kurds present a natural target for ISIS communication and recruitment efforts. ISIS has periodically released video messages in the two main dialects of the Kurdish language, Sorani and Kurmanji. For a while, it even had Kurdish broadcasts from its al-Bayan radio station in Mosul beaming into the nearby Kurdish areas in Iraq. It also published at least one edition of its Nahawand digital magazine in Kurdish, and Kurdish members/supporters of the group have also translated books published by ISIS’s Al-Himma publishing press.

Although there are no accurate figures on the number of Kurds who joined ISIS, some reports indicate around a couple of thousand Kurds in total, and as many as 500 from Iraq and 600 from Iran joined ISIS at the peak of its caliphal rule. It is worth noting that jihadi movements have been present in Iraqi Kurdistan for the past four decades, although their significance has diminished within Kurdish society over time. Since the late 1990s, Kurdistan has witnessed some form of jihadi insurgency—in the form of Ansar al-Islam, Ansar al-Sunna, and other groups/individuals—aligned with global jihadi networks such as al-Qaeda and later the Islamic State in its various iterations. This underlines the Kurdish community’s vulnerabilities to the propaganda and recruitment efforts of jihadi groups.

Facebook is the platform chosen for this study. It is one of the primary social media platforms in Iraq and, up until 2022, ranked as the top social media platform in use in Iraq by the DataReportal website that offers reports and analysis on social media use around the world. In DataReportal’s 2024, Facebook ranked third in Iraq (following TikTok and YouTube), with 19.3 million users out of a population of 36.2 with access to the internet in the country. While Facebook has taken many steps to take down ISIS content, the machine models appear to struggle with detecting such content in foreign languages such as Kurdish. This report argues that the Kurdish-language space on Facebook (or social media platforms writ large) should be regarded as a high-risk environment, vulnerable to jihadi messaging and recruitment. This vulnerability is due to the strategic importance of the Kurdish people’s homeland to ISIS’s central area of operation and the previous effectiveness of extremist jihadi ideologies and groups in recruiting disenchanted Kurdish youths.

Description and Significance of Accounts

This report aims to draw attention to the persistence of pro-ISIS online presence and propaganda on Facebook and the inadequateness of Meta’s monitoring and handling of the Kurdish language space for extremist content/activity. From late March and to mid April, 100 Kurdish-language accounts that contained visual or textual references to ISIS were gathered. The accounts were collected by primarily snowballing from one account to another through friends’ lists or engagement (likes and comments) on the posts. These accounts had either a single post or multiple ones promoting ISIS. Some of the less active accounts might have been created to communicate with other potential pro-ISIS accounts. Not all the posts on these accounts contained direct references to ISIS. While almost all these accounts were private accounts, in at least one case, there was a pro-ISIS public page that, curiously, has been around since 2016, disseminating pro-ISIS books (one private account whose content was publicly accessible disseminated books from ISIS’s Al-Himma Publishing). The bulk of these accounts, 79 percent, were created since 2021, with the rest dating back to the period between 2015 and 2020. This testified to either the account owners’ adeptness and sophistication in avoiding detection or inadequate detection mechanisms (See Figure [1]).

Figure [1]: The following chart shows the year a Kurdish pro-ISIS account’s first post appeared.

The collected accounts disseminated materials produced by ISIS’s official propaganda apparatus or the group’s fan base over the years or posted ad hominem posts in defense of the group. Such content included news of its activities and operations, its ideological content, militant jihadist or broader ultraconservative Salafist understanding of the Islamic creed, and images of ISIS leaders and detainees in prisons and camps. Some of these accounts have not been active for a while (between months to years), and a number of them have locked their profiles. Some accounts that appear inactive might have been active at some point, given their high number of friends and followers, as one account with only three posts has over 1,000 friends. Some of these accounts had clear ISIS-related names, such as one referring to the non-existing ISIS Kurdistan Province or the group’s infamous Hisba Agency acting as the morality police during ISIS’s caliphal rule.

All these pro-ISIS accounts are in the Sorani dialect of Kurdish, which is predominant among Sunni Kurds in Iraq and Iran. There are also significant populations of Shia, Alevi, Yarsani, Yazidi, and Christian Kurds in the region as well but these are less likely to have become ISIS supporters (despite some Yazidi children forcibly converted and recruited by ISIS). Iraqi Kurdistan is the only constitutionally recognized Kurdish autonomous region in the Middle East. Sorani Kurdish is the main dialect of Kurdish used by the government, media, and public education system in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. In Iran, Kurdish is not an official language, although the government tolerates limited use of it for media publication.

It should be noted that there was no evidence that any of the collected accounts were directly or officially connected to ISIS or its active members, although some of them could possibly have formal or informal organizational ties with the group. It is also possible that a number of these accounts might have been created by Kurdish and/or regional security agencies to identify potential ISIS members and sympathizers. Indeed, there was some chatter among some of the collected accounts that warned fellow ISIS supporters to be careful about imposter accounts belonging to local security agencies.

All the collected data was organized into an Excel Sheet document and can be shared with Meta as it is the platform that was investigated for this study. At the time of writing this report, all of the accounts remain on the platform.

Below, I will first provide an overview of the type of content promoted on the pro-ISIS accounts and a range of insights in terms of predominant naming conventions, visual clues, strategies employed to avoid detection by Facebook’s content-moderation teams and tools, and other aspects of the existence and activity of these accounts that might be useful to Meta, and by extension other social media platforms for detecting such content.

Account Naming Strategy/Patterns

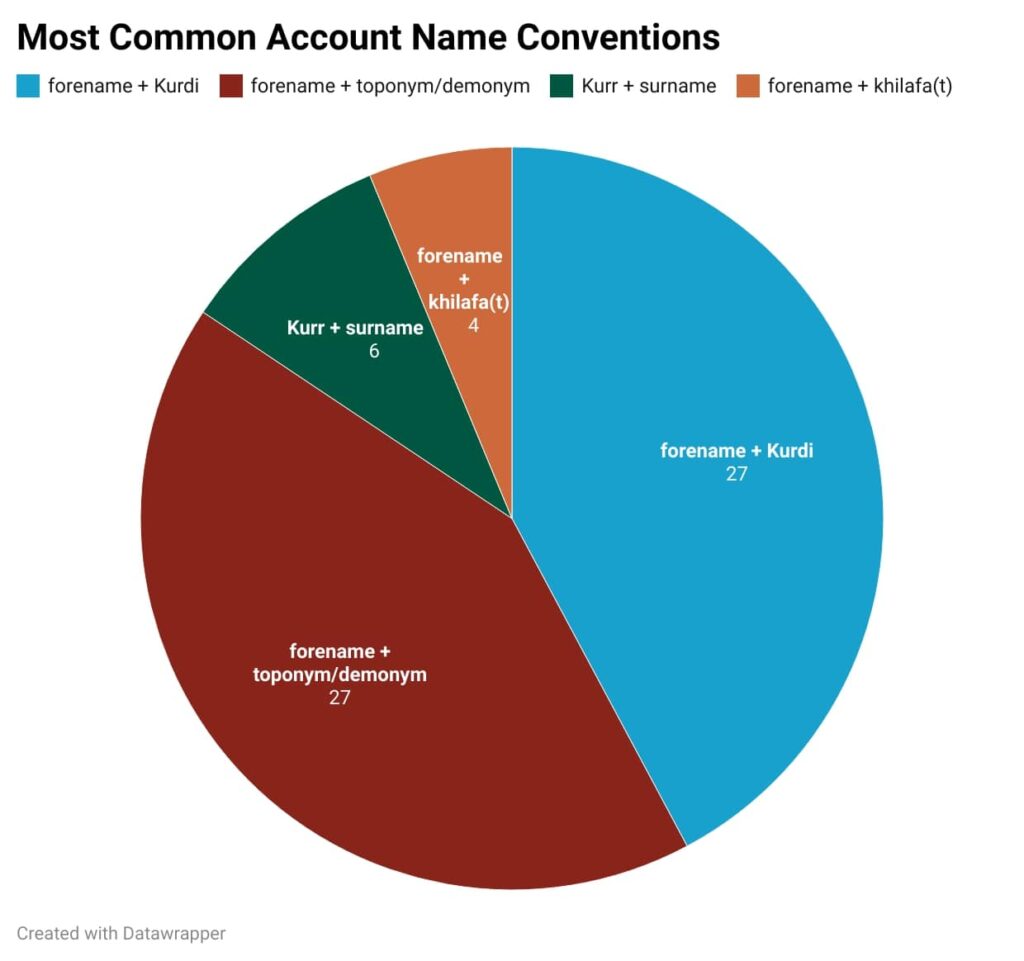

A notable feature of the accounts collected for this study is their names. All account names appear to be names de guerre or not the real personal names of individuals behind them. Certain prevalent conventions could be detected in terms of how the Kurdish-language account names are chosen by their users/owners (See Figure [2]). It should be noted that there are some overlaps among the names in various categories below, with some names fitting into more than one category.

- forename + Kurdi

This is the most common account naming formula, with 27 of the collected accounts named in this way. In this pattern, a personal/individual name, typically Arabic (such as Omar, Mas’ab, Abdullah), is used as the forename in conjunction with the ethnonym Kurdi or al-Kurdi (meaning Kurdish) as the surname. The bulk of these account names use Arabic script, and a few use Romanized script. The popularity of this particular formula could be attributed to its combination of the term “Kurd” to signify an organic connection to the Kurdish people. In doing this, the accounts follow a pattern that has been previously used by some prominent ISIS members in official propaganda video clips by the group, such as Khattab al-Kurdi or Bin Laden al-Kurdi. In short, this is a glaring way of declaring sympathy and/or connection to ISIS as a Kurdish account.

- forename + toponym/demonym

This is another common account naming strategy adopted by 27 accounts with apparent pro-ISIS leanings. This formula includes a forename that could be a common Arabic or Kurdish name, followed by a natural feature, such as “biyaban/sahra” (meaning desert), “chiya” (i.e. mountain), or an actual place name, such as Kurdistan or “Halabjayi” (i.e. from the town of Halabja in Iraqi Kurdistan), “Sharazuri,” (from Sharazur region of Iraqi Kurdistan), “Qarachukh”—the name of a mountain range and ISIS hideout in northern Iraq— or demonym “Kurdistani” and “Almani” (meaning German). Some examples in this category include “Osman Sharazuri” or “Halokani Qarachukh”.

- Kurr + surname

In this variation, the Kurdish word “kurr,” meaning “son,” is used as the forename with a surname that is typically comprised of a toponym such as “biyaban/sahra” (i.e. desert), “chiya” (i.e. mountain), or before terms tied to the Islamic State itself such as “khilafa” (meaning the caliphate). Such combinations occurred six times in the list of accounts collected for this study.

- forename + khilafa(t)

This is a less common combination, with only four accounts following this particular pattern. However, as a naming strategy, this formula is used to signify a clearly purported connection with ISIS by adopting the name of its form of rule and state as the preferred surname. This naming pattern is noteworthy because it explicitly shows pro-ISIS loyalty and has not been detected by Facebook’s content moderation tools and teams.

Figure [2]: The following chart shows the distribution of the most common account naming conventions among the 100 accounts studied here. The remaining 37 account names not included here followed miscellaneous and irregular patterns.

In addition to these formulations, some accounts adopted the names of prominent jihadi figures such as Abu Mas’ab [al-Zarqawi] or [Usama] Bin Ladin.

Propagated Content

To better understand the nature of these accounts’ activities, a thorough search of each account’s content was conducted for visual and textual references supporting the group. Visual references were a common way of signaling the account’s support and sympathies for ISIS. These included renditions of the ISIS logo, flag, and coins. Some accounts posted images of senior ISIS and jihadi leaders, from ISIS’s own leader during the so-called caliphal years, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, to other figures such as al-Qaeda’s former leader Usama bin Laden, Abu Muhammad al-Adnani al-Shami, former ISIS’s spokesperson and external operations’ chief, and even videos of executions and suicide car bomb operations (in the latter case, what they refer to as martyrdom operations).

Visual references also included still images, including memes, and video clips of recent ISIS activities, including by ISIS-Khorasan, ISIS Kurdish militants who were killed during the battle, ISIS’s past official messages and nasheeds (political-religious themed jihadi songs), ISIS militants in Africa, captured ISIS fighters in Syria’s Baghoz in 2019, and sympathy and complaints over camps for detained ISIS family members in Syria, and imprisoned ISIS fighters (see Figure [3]).

Figure [3]: Examples of some visual materials disseminated on pro-ISIS Kurdish-language accounts.

There were also textual references to the groups through the use of phrases such as the “Islamic State” or “caliphate.”

Some accounts employed a notable strategy to avoid detection. For instance, in some videos and images, an emoji was superimposed on the face of an ISIS leader/fighter, ostensibly to mislead Facebook detection software and content moderators. Or in the case of textual references, multiple dots were placed in between the letter to, for instance, render the “dewleti islami” (or Islamic State) in Kurdish as “de..wle..ti I..sla..mi” or spell the words with spaces between letters as “dewle ti Is lam,” or the word “xelafet” (i.e. caliphate) as “x.e.la.fe.t”. In one case, an account even used the digit (9) as a substitution for the Arabic script letter “w” due to their similarity to spell the term Islamic State as “de99le..ti- Isla…m” (see Figure [4]).

Figure [4]: Examples of pro-ISIS Kurdish-language accounts spelling the group’s name with dots and spaces in between letters in a bid to avoid detection by automated moderation software.

It is also important to note that many accounts, when not posting explicitly prohibited or violent materials, engage in propagating content that would initiate individuals into ISIS’s ideology and violent interpretation of the Islamic religion. Many such posts deal with Islamic aqeeda or creed from ISIS’s perspective on a broad range of issues, from tawhid, or the notion of God’s monotheism, jihad, or justifications and calls for armed struggle in the cause of religion/ISIS ideology, the questions of rule, sovereignty, and takfir, or accusations of apostasy and ex-communication including the justification for executions, discussions of the legitimacy of present-day political systems, modern ideologies, democracy/elections, rulers and why they are taghut (tyrant), their supporters and actions of intelligence/security forces in Muslim-majority countries.

Other favorite themes include the questions of al-walaa wal-bara’ or loyalty and disavowingthat in ISIS ideology entails near complete disapproval of pluralism in terms of social/societal diversity, thought, ideology, and lifestyle. The danger of such content lies in its radicalization potential, i.e., preparing certain individuals to be ushered into ISIS’s worldview and ideology gradually until they embrace terrorist violence as legitimate and Islamically justified actions.

What makes detecting and labeling such ideological content challenging is that when it is done in isolation, i.e., without being coupled with prohibited and violent content, it might be, by and large, indistinguishable from content shared by non-activist, non-militant Salafist and Islamist currents (or even some ordinary Muslims). Treading the line between free speech, freedom of religion, and preventing violent extremism and radicalization certainly remains a major challenge for tech companies and law enforcement across the globe. This further underscores the significance of human-performed monitoring, moderation, and decision-making regarding such content.

Content from three radical Kurdish preachers, Mala Kamaran Karim, Mala Ismail Susayi, and Mala Krekar (the latter is currently serving time in an Italian prison for pro-ISIS jihadi activities) are particularly noticeable on pro-ISIS Kurdish accounts. While such content might not often include references to ISIS as such, they typically reaffirm ISIS’s broader worldview with regard to the issues of creed and political ideology and rule, including the use of violence to achieve such goals. Content from such preachers is typically used to denounce the Kurdish political parties and government, other preachers not articulating jihadi and pro-ISIS views, and even Islamist parties seen as submissive and willing to participate in the current political processes in Kurdistan and the broader region.

The dissemination of such content online and its availability for extended periods of time raise questions about how it has managed to evade detection.

Detection Failures and Possible Improvements

Since ISIS’s rise, significant efforts have been undertaken by various stakeholders, including tech companies, governments, and research institutions worldwide, to combat the extensive online activities of the group across multiple languages. The issue was taken up at the highest levels of national and global decision-making, with G7 security ministers in 2018 urging tech companies to do more on their part to eliminate the group’s propaganda. At one point, Facebook claimed that it had removed 1.9 million pieces of ISIS and al-Qaeda content, amounting to 99 percent of such content, from its platform in the first quarter of 2018, although it was not clear if this included one or multiple languages. However, concerns regarding pro-ISIS content evading detection on Facebook persisted in recent years as the group’s supporters have employed a variety of creative ways, from using emojis, including in Kurdish-language accounts, to mixing propaganda materials with content from real news outlets to get their messages out. In recent months ISIS supporters have even begun using artificial intelligence to create fake news outlets with artificial newscasters whose look mirrors that of legitimate news outlets but whose content moves the viewer into the ISIS worldview.

This report contends that the Kurdish-language space on Facebook (or social media platforms in general) should be understood as a high-risk space due to the centrality of Kurdish people’s homeland to ISIS’s core zone of activity and the relative past success of extremist jihadi ideologies and groups in recruiting disaffected Kurdish youths. While specific figures regarding Facebook/Meta’s removal of pro-ISIS content in Kurdish are lacking, the presence of a community of pro-ISIS Kurdish accounts on Facebook is evident. While in purely technical terms, the 100 accounts compiled for this report might be deemed a reasonable “slippage” or “leakage” compared to the accounts removed, from an actual social, societal, and security standpoint, they should raise significant concern regarding ISIS and its supporters’ intentions and plans to target Kurdish audiences. In other words, given Facebook’s widespread usage in Iraq/Kurdistan and the close geographical proximity of core zones of ISIS activity to Kurds, online presence is critical for ISIS to reach Kurdish audiences, build personal relationships, initiate ideological indoctrination, and ultimately increase recruitment.

Due to gaps in existing research, the precise nature and scope of Facebook’s content detection and moderation strategy in the Kurdish language space remain uncertain. This study emphasizes the necessity for a more robust strategy in two key aspects: Firstly, enhancing automated detection methods by incorporating specific textual and visual elements into Facebook’s moderation and detection models. In this regard, it is imperative to integrate insights from current and past studies regarding prevalent usernames, profiles, header conventions, and other textual and visual indicators utilized by ISIS. Secondly, this report underscores the importance of augmenting manual sifting and detection mechanisms. In this context, as highlighted in this report, employing snowballing techniques and examining friends’ lists, as well as interactions such as likes, comments, shares, and tags on pro-ISIS posts, proves crucial for identifying pro-ISIS accounts and activities. However, it’s important to note that not all individuals in the friends’ lists or engaging with such posts necessarily sympathize with ISIS. To enhance these efforts, there is a need to invest in additional resources by recruiting local experts proficient in the regional language, culture, socio-political dynamics, and online behavior patterns of extremist groups.

While it might be true that the Kurdish-language market on Facebook is minimal and marginal for Meta in terms of its share of profit in the platform’s overall global revenue, the Kurdish language space is important for the security and political reasons mentioned above. Hence, market-centered and profit-driven imperatives should not trump efforts to counter persisting pro-ISIS activity in Kurdish-language space on Facebook (or social media platforms at large). This would be short-sighted and counterproductive, considering its implications for security and social-political stability. Marginalized and disadvantaged communities constitute some of the ideal niches for propaganda and recruitment by extremist groups of all stripes. Tech companies, as major conduits of information and digital interactions, must strike a balance between market-driven imperatives and their social and political responsibilities.

A more robust and dynamic approach, combining more rigorous automated and human-performed content detection/moderation strategies, is essential to deter ISIS loyalists from establishing and maintaining an online presence. It’s important to acknowledge that such a strategy cannot guarantee the complete eradication of extremist content. Nevertheless, this should not deter efforts to pursue a more stringent method of detecting and countering violent extremist rhetoric and activities online.

While this report primarily focuses on the role of tech companies, notably Meta, there exists a crucial role for government agencies in Iraqi Kurdistan. Leveraging their linguistic capabilities, expertise, and familiarity with the behavior and culture of local extremist organizations, these agencies should adopt a more proactive approach. This involves A) identifying extremist content in various Kurdish dialects and B) engaging in communication and coordination with social media platforms to remove such content. Such collaboration would foster mutual benefits, enhancing local security and stability while creating a safer online environment by depriving extremist groups of critical space to exploit and reach potential targets for indoctrination and recruitment.

This report focused on an admittedly limited, but important dataset. Employing computational techniques to analyze extensive Kurdish data on Facebook (or other social media platforms) or conducting manual searches over an extended period with a multi-member research team and multi-sited data collection approach could offer varied insights. Such methods could further enhance efforts to safeguard the online sphere from extremist propaganda and outreach.

* The author is a Senior Fellow at the Philadelphia-based Foreign Policy Research Institute. Salih has over two decades of experience researching and writing on Kurds, extremism, ISIS, and Middle Eastern regional affairs. He holds a doctoral degree from the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School of Communication, where he wrote his dissertation on ISIS’s discursive articulations of identity, political community, and statehood/rule. He is on X @MohammedASalih.

This Post Has 0 Comments