The American Women of ISIS

Marie Claire article quoting ISCVE Director Anne Speckhard, Ph.D.

by Kate Storey

April 22, 2016

by Kate Storey

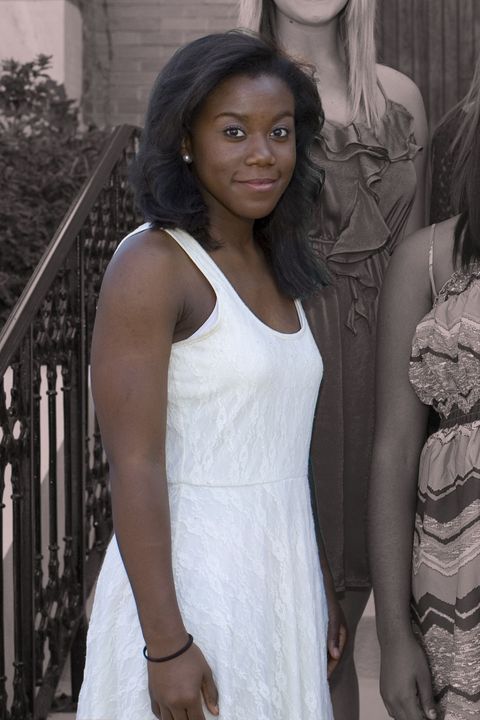

Shannon Conley met a guy online. She was 19, a normal Colorado teen with glasses and a big, toothy smile. He was 32.

One day in early 2014, Conley nervously told her father that she had a new boyfriend. She wanted her dad to meet him, so she set up a Skype call on her laptop. During the chat, the couple asked for his blessing to marry. They also told him that Conley would be moving to Syria, where they would wed and start their lives together.

Their lives, they told him, would be dedicated to ISIS.

Conley had recently converted to Islam after researching the religion online, and felt strongly about righting the global wrongs against Muslims. Then, adopting an extremist stance, she decided she wanted to lend her skills as a certified nurse’s aid to ISIS—also called the Islamic State, and known the world over as the vicious terrorist group responsible for brutally murdering countless victims and inciting new levels of global fear. They, she thought, were the way to do it.

Her dad was shocked. He pleaded desperately with his daughter, trying to change her mind.

It didn’t work. Soon after the Skype call, he found a one-way plane ticket to Istanbul, Turkey on his desk. From there, she would be driven to ISIS-controlled territory in Syria.

On April 8, 2014, Conley was arrested at the Denver airport before she even boarded the flight. She was charged with attempted provision of material support to a designated foreign terrorist organization, and is currently serving a four-year sentence in federal prison.

Shannon Conley

Conley’s decision to join ISIS wasn’t made on a whim—she’d been talking to ISIS recruiters online and reading extremist materials that, together, pushed her to a radicalized point of view. And according to court documents, she’d been on the FBI’s radar for almost a year before her arrest, when a local church accused her of mapping out the building’s layout. She defended herself to agents by explaining that she felt she’d been followed by members of the church. “If they think I’m a terrorist, I’ll give them something to think I am,” she said in an FBI interview. Over the following months, Conley claimed she was considering going to Iraq to join a jihadi training camp and wanted to wage jihad on the U.S.

Female terrorists are hardly a new phenomenon. From the militant women of the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s to the all-female suicide bombing units of Sri Lanka’s Tamil Tigers in the ’90s and ’00s, women have played critical roles in terrorist organizations across the globe for decades. And while the women pledging their allegiance to ISIS aren’t necessarily joining their male counterparts on the battlefield, their involvement in the terrorist group is paramount: They recruit new members, helping ISIS become a bigger and deadlier force.

ISIS has recruited as many as 30,000 foreigners in the last five years, according to the New York Times. The U.S. government estimates that about 250 Americans have tried or succeeded in getting to Syria to join ISIS in that time, and according to George Washington University’s Center for Cyber and Homeland Security, women account for approximately 13 percent of Americans charged with ISIS-related crimes. “We’re seeing a resurgence in women’s involvement in terrorist groups,” says Audrey Alexander, a research fellow at GWU.

ISIS is now pursuing a chilling new strategy: recruiting teenage girls online.

It’s not a fluke—it’s because ISIS wants it that way. The group creates propaganda that specifically targets women, and sells them a different message from the one sold to men (though both are told it’s their religious obligation to join the Islamic State). Men are marketed the chance to prove their faith by joining the fight; women are marketed the idea of sisterhood and the opportunity to marry a jihadi fighter, thus supporting the cause by raising the next generation of militants.

ISIS has at least 40 media organizations pumping out video, audio, and written material, according to Humera Khan, executive director of Muflehun, a think tank specializing in counter terrorism. But the materials intentionally skirt the more extremist side of ISIS culture. “Instead, they’re talking about everyday issues, what life is like. It’s very warm and fuzzy stuff,” Khan says. “Only a tiny percent has anything to do with religious ideology and a tiny percent has anything to do with violence.”

Melanie Thortis/The Vicksburg Evening Post via the AP

The ISIS caliphate is portrayed as a perfect, idyllic Islamic community. There are photos of markets teeming with vibrant fruits and vegetables, children laughing and playing games in the town square, and militants splashing around in a glittering swimming pool. One much-circulated Twitter photo (which has since been deleted) even showed fully covered women thought to be Australians holding weapons while posing in front of a shiny, white BMW.

“There’s a priority for the Islamic State to attract females because it offers stability. If you want people to see you as a nation, a legitimate state, it’s important to attract females and have them start families,” says Veryan Khan, editorial director of the Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium (TRAC). “It’s not like women are an afterthought. This is a strategic move.”

But while women have always been valuable targets to terrorist groups, ISIS is now pursuing a chilling new strategy: recruiting teenage girls online.

In October 2014, three high school girls from Denver cut class to catch a plane to Syria after chatting with ISIS supporters online. In May 2015, Jaelyn Young, a 19-year-old former honor student and cheerleader from Mississippi, was arrested on suspicion of attempting to travel to Syria to join ISIS with her American boyfriend. Young sent messages to FBI agents she thought were ISIS members, saying, “I cannot wait to get to Dawlah [ISIS territory] so I can be amongst my brothers and sisters under the protection of Allah swt to raise little Dawlah cubs In sha Allah [God willing].”

The United States government is taking notice. At a recent roundtable on Capitol Hill organized by Representative Martha McSally called “Women and Terrorism,” three members of the House Committee for Homeland Security and three experts met to discuss the growing threat of the women of the Islamic State. But addressing the international problem of female recruitment also means reframing how we envision women overall.

“When it comes to conversations about ISIS and women in particular, there’s a tendency to oversimplify, to focus on women as victims, maybe even to think of Muslim women as docile and obedient,” said Congresswoman Kathleen Rice of New York. “There’s no question that many, many women have been victimized by ISIS. But there are women who are actually going to join the fight—not on the frontline but as enforcers, as wives, as mothers. We’ve got to figure out why.”

RECRUITMENT

It doesn’t take much to catch the eye of ISIS recruiters, who aggressively monitor social media.

“The moment you indicate any sort of interest in ISIS or ask any questions about it on a social platform, you get 500 new followers on Twitter, you get 500 friends on Facebook, you start getting emails and messages constantly—it’s a kind of love bombing,” explains Mia Bloom, Georgia State University professor and author of Bombshell: Women and Terrorism, of the remarkably systematic way the process works. “All of a sudden, you feel really popular, important, and significant because of this flood of attention. And it all wraps up in the same ideology they message over and over: ISIS can give you something emotionally and psychologically that you will not have unless you come to the Islamic State.”

On Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Tumblr, users indicate their allegiance by using the moniker “IS,” “Islamic State,” or “Dawlah” (the group’s preferred names) in their private profiles. Some feature the ISIS flag in their banner or profile picture, while others post photos dotted with the symbol. Many boast in their bios about how many times their accounts had been shut down and direct followers to alternative accounts.

“The moment you indicate any sort of interest in ISIS, you get 500 new followers on Twitter—it’s a kind of love bombing.”

After a recruiter makes initial contact, they will take the conversation to more private online platforms like Kik, WhatsApp, or, the new favorite, Telegram, an encrypted messaging app which gives senders the option to have a message self-destruct after it’s read. (Recruiting efforts used to be more public but, in February, Twitter announced that it had suspended 125,000 ISIS-related accounts. A few discreet public accounts located by MarieClaire.com feature links leading to the website justpaste.it, where ISIS members can post propaganda that goes undetected by search engines. Users can only access the pages with an exact link.)

ISIS sympathizers posting propaganda could be anywhere in the world: Syria, Iraq, or sitting in a coffee shop in the Midwest. But for those who travel to ISIS-controlled territory, recruiting takes on an official capacity. Many of the Western women who join the Islamic State are sent to a room and given the full-time job of recruiting women just like them, explains Anne Speckhard, author of the study Brides of ISIS: The Internet Seduction of Western Females into ISIS.

When a one-on-one connection is established over an app, female recruiters then engage in a social media language that’s very familiar to the women on the other end: emojis, memes, internet shorthand, and quizzes. Women are seen as invaluable in these roles because they can relay ISIS-approved messages back to their home countries in accessible, colloquial terms.

“It makes it feel more like the recruiter is just like you, a friend.”

“You have French girls messaging French girls and American girls messaging American girls,” Bloom explains. “It helps with relating, finding common ground. It makes it feel more like the recruiter is just like you, a friend.”

As further incentive, potential recruits are then romantically matched with a jihadist fighter. In some cases, like Conley’s, the relationship will start online. In other cases, a “sister” will promise to pair the recruit once she arrives at ISIS-controlled territory. Whatever the method, a woman is encouraged to marry as soon as possible. Otherwise, she’ll be relegated to the single woman’s dormitory until she’s matched up.

Katja Cho + Sandy Pan

LIFE ON THE OTHER SIDE

If Conley had made it to Syria, she would have found a reality much different than the one she saw online. According to Marilyn Nevalainen, a Swedish 16-year-old who escaped from ISIS-controlled territory in Iraq, living conditions were much worse than she was accustomed to. “When I was there I didn’t have anything: no water, no electricity, didn’t have any money either. It was a really hard life,” she told Reuters.

Though highly-circulated promotional photos and videos on social media show “sisters” holding Kalashnikov rifles and practicing their shots, the women of ISIS aren’t allowed to fight or carry out suicide bombings. It’s probably tempting for the organization to bend the rules—some terror groups that originally kept women from fighting, like Al Qaeda and Boko Haram, eventually changed their stance because of women’s ability to sneak into public places while wearing bombs without raising suspicion, sometimes even strapping devices around their bellies to appear pregnant. But publicly released ISIS regulations reveal that their rules for women are uncompromisingly strict, says Bloom.

The free will with which Western women join ISIS is stripped the moment they sign up.

“They said, ‘No you’re not going to have an active role; You’re not going to be on the front lines; You’re not going to be fighting,'” Bloom says of the report, published in Arabic and not intended for a Western audience. “‘You’re going to be home. In fact, you might not be allowed to leave the house. You might get a husband who is from a very conservative society who won’t let you leave the house at all.'”

So while Conley, who’d trained with the U.S. military cadet program Army Explorers, expressed an interest in fighting, she likely would’ve instead joined a recruiting committee, where she’d perpetuate the same cycle that hooked her: Message American girls back home. Her only other option? Join the Al-Khansaa brigade, an all-female police force that punishes other women for moral disobedience including infidelity and violations of the full-burka dress code.

Former female members of ISIS’s Al-Khansaa brigade speak to the brutality of lashing other women who broke dress code:Former ISIS Wives and Members of the Al-Khansaa Brigadeby Marie Claire USPlay VideoShare

According to a recent New York Times report, rape is rampant among ISIS fighters. To ensure that the women, usually of the Yazidi religious minority, don’t become pregnant, the men force them to take birth control. Raping a pregnant slave isn’t allowed, according to an interpretation of Islamic law reportedly cited by ISIS.

The enslavement doesn’t end there. Most women can’t leave their homes without an escort in ISIS-controlled territory. Experts say Western women aren’t explicitly banned from walking around, particularly with other Westerners, but, just like everyone else, they’ll be witness to the brutal violence in the public squares.

“They take people to the square and they behead them and they require people walking around to come and watch it,” says Speckhard, who has interviewed dozens of ISIS defectors. “It’s impossible to miss the brutality.”

rape is rampant among ISIS fighters.

If her husband died fighting, Conley would be moved to a dormitory called a maqar with other unmarried women and then swiftly married off to another fighter—with or without her consent. While many interpretations of Islam dictate that a woman not marry until four months and 10 days after her husband’s death, ISIS often cuts that period short, choosing another groom for the widow as quickly as possible.

If Conley decided the caliphate wasn’t what she expected and wanted to return to her family back in Colorado, she’d find herself trapped. The free will with which Western women join ISIS is stripped the moment they sign up.

“If you want out, you have to rely on a smuggler to get you out. That can cost a lot of money,” Speckhard says. “You have to find a smuggler you can trust. If you’re a woman, he’ll probably rape you, or the smuggler will say, ‘I’ll help you if you have sex with me.'”

WHAT’S BEING DONE ABOUT IT

When it comes to preventing terrorist recruitment, experts advocate for gender-neutral strategies, since the same environmental factors that compel men to join are also found in women: a feeling of alienation in their home country or a radicalized sense of religious obligation.

Some government officials like Homeland Security Committee chairman Michael McCaul count Twitter’s sweep of ISIS profiles to be a huge step in the right direction. “Google now has counter-narratives that pop up when you type in certain key phrases. And that’s the kind of stuff we need more of,” he says. “NGOs on the ground and religious leaders providing that counter-narrative are really key as well.”

According to Mubin Shaikh, a former extremist who has since become an undercover counter-terrorism operative, hands-on work is already being done behind the scenes. “In the U.S. and Canada, it’s being done quietly, without funding, and without government direction,” he says.

But there’s more to think about than simply trying to stop terrorist recruitment in our own backyard. “When you’re talking about countering violent extremism, you have to look beyond just prevention,” says counter-terrorism expert Humera Khan, who explains that while prevention means raising the barriers to entry, intervention focuses on those who’ve already crossed the line. “If someone has already been indoctrinated but hasn’t committed any criminal acts, how do you stop them? How do you pull them back before they’ve passed the point of no return?”