Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Militant groups such as the Islamic State (IS) and its…

ISIS and the Allure of Traditional Gender Roles

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08974454.2021.1962478

by Anne Speckhard and Molly Ellenberg

Abstract

As issues of repatriations of ISIS members and their families are hotly debated, exploring the factors that led over 40,000 men and women to leave their home countries to join ISIS is integral to rehabilitating and reintegrating these individuals. Understanding their experiences in ISIS is critical to deradicalization. This article uses primary data to explore vulnerabilities, motivations, influences, experiences, and sources of disillusionment among ISIS members through a gender-based perspective. Men and women’s ISIS trajectories were impacted and informed by gender, particularly by a desire to solidify masculine and feminine identities in ISIS’s Caliphate, where traditional gender roles were both glorified and brutally enforced.

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS] was unparalleled in their recruitment of foreign terrorist fighters [FTFs], their use of the Internet and social media in their recruitment efforts, and their multibillion-dollar war chest, unmatched by any other terrorist group. ISIS also pursued, unlike any other terrorist group, unprecedented recruitment of women with promises and propaganda that was attractive to and that resonated with women (Tarras-Wahlberg, 2017; Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2018). While other militant jihadist and terrorist groups of other ideologies have used women in specific but limited support and fighting roles, as did ISIS at times, the group mainly recruited women to live under their so-called Caliphate and to serve the group as wives and mothers, responsible for producing and raising the next generation of ISIS fighters (Almohammad & Speckhard, 2017; Gan et al., 2019). How ISIS was able to recruit such large numbers of women has been the focus of numerous studies, and the gendered aspects of both male and female membership in ISIS have been examined to a lesser extent. Gender, as it relates to ISIS, has not been studied as thoroughly through a psychosocial lens, however, and has not been studied at all through the use of primary data from ISIS men and women themselves.

This article aims to fill these gaps by using firsthand interview data from 259 ISIS men and women to examine the psychosocial aspects of joining, participating in, and leaving ISIS, and how those aspects are informed by gender. It begins with a literature review of gender and terrorism more broadly, as well as the gendered aspects of ISIS radicalization, recruitment, and membership. The article then uses quantitative and qualitative analyses of the primary interview data to explore how men and women experienced ISIS, from their early vulnerabilities and influences to join, their motivations for joining, their roles and experiences in the group, and their sources of disillusionment with it. Throughout the analyses, a special emphasis is placed on gender-specific experiences, gender-based violence, and the impact of gender norms and traditional gender roles on ISIS foreign fighters’ decisions to join the group.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Gender and Terrorism Broadly

Issues of gender and terrorism have been highlighted over the last four decades, with researchers focusing not only on women’s roles in terrorist groups as agentic, active supporters and perpetrators (Speckhard, 2008; Bloom, 2011; Fink et al., 2013), but also on the impact of masculinity on men’s decisions to join terrorist groups and engage in terrorist violence (Aslam, 2012). Many of these studies focus on women’s involvement in militant jihadist groups, unsurprisingly, given that these groups often draw the most ire in the Western world, at least in part for their brutal oppression of women. The idea that women would willingly support or act on behalf of a group that would seek to strip them of their basic human rights has been unfathomable to the public, and yet the phenomenon is all too common and still not well understood.

Indeed, female involvement in terrorism creates a deep fascination among the lay public, as the violence of women is something that society tends to deny; thus, female involvement in terrorism often creates a media frenzy. For instance, the use of Chechen women in the Moscow Dubrovka theater hostage-taking riveted international media riveted and brought attention to the Chechnya issue in a completely new manner (Speckhard & Akhmedova, 2006). Similarly, in Somalia, one Western woman, Samantha Lewthwaite, caught the eye of both media and counter terrorism experts for her role in supporting the al Qaeda-linked al Shabaab. Lewthwaite, sometimes referred to as the “white widow,” is considered one of the most wanted women in the world for her fundraising on behalf of a number of al Shabaab terrorist attacks. While Lewthwaite willingly served the group, notably, scholars have found that delving into Lewthwaite’s personal life and possible causes for becoming a terrorist, rather than her espoused terrorist ideology and actions, is often the focus of news stories about her, demonstrating a difference in the media’s coverage of male and female terrorists (Auer et al., 2019). Female terrorists, argue Gentry and Sjoberg (2016), are less likely to be viewed as rational actors and more likely to be viewed as emotionally driven than their male counterparts. Similar to the media, security services around the world often refer to them as victims and see them as manipulated by men, rather than having personal agency in their decisions to join terrorist groups.

Indeed, terrorism in general appears to be a man’s world, with few groups having equal numbers of female participants and even fewer having females in leadership roles. Yet, Sjoberg and Gentry posit that female terrorists are a minority, but not a rarity, noting that Lewthwaite’s “white widow” name was inspired by the Russian government’s referring to women terrorists in Chechnya as “black widows,” whose own agency in their terrorist actions may be sorely underestimated, given that they were seen as widows versus active terrorists from the start (Gentry & Sjoberg, 2016). Notably, the first author studied these “black widows,” finding that many were traumatically bereaved, but not necessarily widows, and all were deeply traumatized, primarily through directly witnessing or hearing about the deaths of their husbands and family members at the hands of the Russians, and they had volunteered for, rather than been coerced into, their missions, for the most part. Their motivations ranged from revenge to religious ideology, and to deny them agency in their acts would be misguided and patronizing (Speckhard & Akhmedova, 2006). Likewise, it should be noted that the Chechen terrorists used women suicide bombers in equal numbers to males from the start, unlike their Arab counterparts who only turned to using female bombers when males could no longer pass security impediments. Similar motivations and degrees of agency were found among many female Iraqi and Palestinian terrorists, as well (Speckhard, 2009; Sela-Shayovitz & Dayan, 2019).

Women have also been involved in terrorist organizations of other ideologies, with Weinberg and Eubank (2011) highlighting that militant jihadist organizations were later accepters of female terrorists, as many traditionalist Middle Eastern societies see women’s place as in the home and women’s participation had to be religiously sanctioned. In contrast, women have held leadership roles in far-left terrorist and violent extremist organizations for many decades. Some have argued that women’s inclusion in far-left groups has made those groups less likely to use violence to achieve their desired goals, while others have pointed out that women can be the most violent among these actors (MacDonald, 1991; Weinberg & Eubank, 2011; Asal et al., 2013). Women’s current participation in far-right groups is increasing but largely remains relegated to support roles. There is also evidence that far-right women who perpetrate violent extremist crimes often do not adhere to the ideology as closely as their far-right male or their far-left female counterparts. In both far-right and far-left groups, relationships play a meaningful motivational role for participation of female perpetrators, as has been seen in militant jihadist groups, as well (González et al., 2014).

In the midst of a discussion of women’s agency in terrorist acts, it cannot be denied that women are at time forced into terrorist roles. In Iraq, there was evidence that some women were being coerced into suicide missions (Speckhard, 2009) and there were cases of coercion in Palestine as well, although in the second intifada, senders of suicide bombers reported that women were volunteering for missions much more frequently than men (Speckhard & Akhmedova, 2005). Boko Haram, the recently ISIS-linked militant group that has been terrorizing Nigeria over the last twenty years, has repeatedly targeted women for gender-based violence and abductions, but has also recently begun using women instrumentally, such as by carrying firearms and explosives under their niqabs. Many of these women were abducted into the group, raped or forcibly married, and are believed to have been forced into suicide bomber roles. Of course, Boko Haram’s utilization of women in specific roles has not precluded their continued violent treatment of women, particularly in enforcing traditional gender roles (Zenn & Pearson, 2014).

There is no doubt that females are useful to terrorist groups for their ability to pass security borders, as they are often viewed with less suspicion and are not questioned in many settings for hiding their identities or bodily searched due to considerations concerning female modesty. During the second intifada in Israel and Palestine, as well as later when al Qaeda in Iraq was in retreat, terrorist groups turned to sending women as suicide bombers for this reason—they were more likely than men to succeed in their missions. ISIS did the same to a lesser extent in Mosul. Men dressing as women to evade security measures is also prevalent among terrorists. Men in Boko Haram, for example, have also been known to wear niqabs as disguises in the execution of their attacks. ISIS male cadres told the first author about dressing as women to try to evade drones overhead and one ISIS woman dressed her son in niqab to help him escape.

Recognizing that the impact of gender should be investigated with regard to both men and women, there has also been recent research on masculinity and terrorism, specifically militant jihadist terrorism. Aslam (2012) described militant jihadist terrorism as a form of “gender performativity” for Muslim men, wherein they engage in violence in order to regain perceived masculine honor lost through social, political, and economic circumstances. Aslam also notes that militant jihadist terrorism arises as a result of multiple masculinities, each of which may be impacted by cultural, political, and socioeconomic contexts. For example, men who feel that they are unable to be breadwinners for their families may engage in political or interpersonal violence as a form of “protest masculinity.” Moreover, men who feel that discrimination and marginalization have caused them to lose their male right to dignity and self-respect may use violence as a form of “hegemonic masculinity” in order to assert their dominance (Aslam, 2012). In a similar vein, Duriesmith (2016) argues more broadly that “new war” can be explored as a way for subordinate men to “challenge the existing distribution of power in society.” Within the militant jihadist context, Muslim men may be viewed as a subordinate group within the existing patriarchal global society, whereas men from post-colonialist societies represent the dominant group. Muslim and Arab men’s feelings of frustration, humiliation, and emasculation have also been tied to the Arab Spring uprisings (Amar, 2011).

Gender and ISIS

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS], which took great advantage of the feelings surrounding the Arab Spring uprisings, made waves in the realms of counter terrorism and terrorism research for a myriad of reasons: Unprecedented wealth, unprecedented lethality, unprecedented Internet-based recruitment, and unprecedented recruitment of foreign terrorist fighters [FTF], to name but a few. Their recruitment of upwards of 40,000 FTFs has been attributed to a variety of factors ranging from geopolitics to social media, but it is also estimated that no less than ten percent of those FTFs were women, with FTF cohorts from some countries having far larger proportions, sometimes up to 50%, of women. At the time of this publication, it is estimated that at least 4,000 women traveled from outside of Iraq and Syria to join ISIS, though that number is likely quite a bit larger (Schmid & Tinnes, 2015). More than any other terrorist group in history, ISIS attracted unprecedented numbers of foreign fighters and within this, the sheer number of women who joined ISIS was unique, as was their diversity, in contrast to previous terrorist groups, who far more often either did not use females or relied on local women versus attracting them as foreign fighters (Saltman & Smith, 2015). This was likely due to ISIS’s wealth and control of significant territory and having established themselves as a proto state, their ability to offer to women, as no other terrorist group before could offer, a comfortable life as a wife and mother. Although male and female travelers into ISIS are generally referred to as foreign fighters and ISIS women served in a number of different roles including at times as combatants, despite this label, their primary role as defined by ISIS was that of wife and mother.

Many women were drawn to live under the ISIS Caliphate by their shared anger with men over Assad’s injustices and global politics that underlined militant jihadist claims that Muslims, Islamic lands, and Islam itself are under attack. Likewise, ISIS’s online propaganda and recruiters promised women a utopic state in the making that offered them better and easier lives with free housing, salaries for their husbands, and a life free of discrimination and the constraints and pressures of secular society. ISIS propaganda featured women holding idealistic traditional gender roles as they helped build the longed-for Islamic Caliphate. This imagery was attractive to religiously conservative Sunni Muslim women facing Islamophobic discrimination and liberal lifestyles that conflicted with their values and who longed for a simpler and purer environment with clear black and white rules (Spencer, 2016). ISIS’s empowering propaganda also appealed to women living in conservative households where decisions were being made for them about their futures, as ISIS religiously justified and empowered their taking their futures into their own hands by deciding to travel to join ISIS.

ISIS’s online propaganda, disseminated through already hyper-gendered online communities, emphasized traditional gender roles, not only for women, but for men as well, and members of these communities engaged in online shaming of men into fighting and policing women’s self-portrayals, much as they would in the offline Caliphate (Pearson, 2018). There is certainly an argument to be made that ISIS’s gendered messaging did not empower women—rather, the messaging empowered ISIS using women—and gave women a platform only to restrict the freedom of other women. This misses the efficacy of such gendered messaging and the profound impact it had on convincing women and girls that they were religiously justified to throw off constraints they felt at home and defy even their parents or non-ISIS endorsing husbands as well as their governments. It empowered them through religious argumentation and emotional appeals to make the decision on their own to leave their homes and sign up for the religiously sanctioned adventure of coming to live under the ISIS Caliphate.

In fact, ISIS’s recruitment materials, especially those targeted toward Westerners, utilized specific language to convey their messages when they discussed women’s subjugation so that the reader could see even female slavery as empowerment. For example, one purportedly female writer of an article in ISIS’s English language Dabiq magazine took great pains to emphasize the distinction between prostitution and legal sexual slavery, referencing that Ismael, one of the Prophet Muhammed’s earliest and most revered ancestors, was born to Abraham and his slave, Hagar, and not his wife (Lahoud, 2018). Likewise, ISIS’s use of sabaya—captured female slaves—was marketed by ISIS as a religiously sanctioned benefit for women who would come to join ISIS in that they could have free domestic servants and finally turn any sense of societal subjugation they had previously experienced around on to others.

ISIS publications also put forth images of women in combat and suicide attacker roles in order to attract women who wanted to engage in militant jihad or sacrifice their lives for the greater cause (Lahoud, 2018). As Peresin and Cervone (2015) astutely note, the encouragement of women to take up arms for ISIS may not have been as meaningful for women living under the Caliphate (though there is evidence that some ISIS women did carry weapons, wear suicide belts, and at times explode themselves) as it was for women living outside of the Caliphate. If these women were unable to fulfill their obligation to make hijrah, that is, migrate to live under shariah, they could find solace in the fact that they could still contribute to ISIS by committing violent attacks at home, particularly in Western countries. Indeed, al Qaeda had already paved the way in the West for using female actors, with Belgian Muriel Degauque and British Roshonara Choudhry as prime examples (Bloom, 2011).

There has been ample research on the radicalization and recruitment processes and roles of ISIS women. For instance, Pearson and Winterbotham (2017) found that ISIS’s near-term territorial goals (as opposed to al Qaeda’s long-term dream of a Caliphate), required the involvement of women and families in order to establish a physical, functioning state, rather than simply an army of fighters. This necessity of women to achieve ISIS’s aims adds perspective to the frequent portrayal of ISIS women as naïve “jihadi brides”; rather, it is clear that from the perspective of the group and the women themselves, that they were empowered by ISIS to act as state-builders through their adherence to traditional gender roles (Pearson & Winterbotham, 2017). Emblematic of women’s commitment to the role of raising the next generation of militant jihadists is the estimate that at least 730 babies were born to foreign parents in the ISIS Caliphate, and this is likely a low estimate given the high rate of infant mortality (Cook & Vale, 2018).

There has also been extensive study on the psychosocial aspects of ISIS radicalization, recruitment, and membership (Kruglanski, 2014; Jasko et al., 2018; Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020b). However, most of the research regarding ISIS and gender focuses exclusively on women, with men seemingly representing the default ISIS member, despite the aforementioned unprecedently large numbers of female members (Ali, 2015; Chatterjee, 2016; Kneip, 2016; Pearson, 2016). The archetype of the “ISIS bride” has been described in numerous press reports, referring to young Western women, often converts to Islam of European descent, who were seduced online by ISIS recruiters and traveled to Syria in the hopes of pursuing adventure, romance, and marriage or who blindly followed their boyfriends and husbands into ISIS (Martini, 2018). This portrayal of ISIS women denies women an agency that most very clearly possessed. Delving into the motivations and vulnerabilities of these women through in-depth psychological interviews, the first author found deeper psychosocial needs, political concerns, and often a strong sense of agency in joining ISIS to meet these needs. Many were angered over geopolitics and what was happening in Syria and believed they could make a difference, or they wanted to contribute to the rise of an Islamic State, believing it was the longed-for Caliphate. Others became convinced that it was their Islamic duty to make hijrah and migrate to live under ISIS’s shariah and serve ISIS’s Caliph. Some simply wanted to escape negative circumstances at home, believing they could do so by escaping into a utopic Caliphate. Some were adventure seekers or fell in love with men who recruited them over the Internet. Some women felt alienated, discriminated against in their home countries and believed that ISIS could provide them with more than the surface-level draw of a husband or decided with their husbands to go to join the Caliphate. They believed that ISIS would provide them with a holistic Islamic environment where all citizens must adhere to their religious customs and they could raise their children free of Western moral degradations (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2018). Yet, these more profound aspects of women’s membership in ISIS have not been examined extensively by other researchers, and even more rarely through the use of primary data. Saltman and Smith (2015) provide extensive analysis on the various “push and pull” factors contributing to Western women’s decisions to join ISIS utilizing their social media posts. The two authors found, in addition to the great diversity previously referenced, that women’s “push” factors were similar to men’s, as they relate to feelings of marginalization and Islamophobia, specifically, but that women’s “pull” factors were phrased in a far more gendered way. These factors include the religious obligation to make hijrah and the opportunity to play a role in building the Caliphate, feelings of belonging and sisterhood in particular, and romance. All of these “pull” factors tie into what Saltman and Smith call ISIS’s “warped feminism,” wherein women feel valued and empowered by the group that is calling them to join and therefore motivated to join ISIS (Saltman & Smith, 2015). Indeed, although ISIS is inarguably a patriarchal and sexist organization, they did empower women through religious argumentation to defy non-ISIS endorsing husbands, parents, and governments to decide on their own to travel and join the group.

The needs and desires that motivated women to join ISIS are not unique to women. Men, too, have psychosocial needs, many of them also gender-based, which ISIS recruiters also promised to fill. ISIS offered men the opportunity to live in an environment marked by traditional and historical gender roles, where men could become warriors, providers, and protectors of their families. Unfortunately, the cruelty and brutality of ISIS often meant that masculinity also consisted of violence and misogyny, which also appealed to some who felt diminished in their home countries and longed to dominate and command respect as “real” men (Necef, 2016).

The existing literature approaching ISIS from a gendered perspective primarily discusses the roles and experiences of women in the group. This is a crucial area of study given the unprecedented number of women who traveled to join ISIS and lived under its Caliphate. Moreover, the vast majority of foreign adults remaining in Syrian Democratic Forces [SDF] territory, hoping to be repatriated, are women. Therefore, it is undoubtably important to understand who these women are and what they have experienced over the past years. Certainly, the flow of foreign women to ISIS as compared with other terrorist groups can largely be attributed to the mere existence of the territorial Caliphate, but there are a number of other aspects of ISIS’s attractiveness to both men and women that can and should be viewed through the lens of gender. Moreover, the lack of primary data from both men and women members of ISIS is a major gap in the literature. While a great deal can be learned about women’s motivations for joining from their social media accounts, interviews with friends and family members, and open-source data, as has been shown in the rich yet limited research on this topic, there is far more to be discovered through direct interviews with the women themselves. Furthermore, there is also very little primary data from ISIS men, especially as it relates to issues of masculinity.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The present study aims to use primary data to fill the psychosocial gap in the ISIS and gender research and to look at the impact of gender on ISIS men as well as women. This article examines the role of gender in a wide range of aspects of ISIS, from recruitment, to roles, to sources of disillusionment with the group. Through the lens of 259 in-depth semi-structured psychological interviews with male and female ISIS defectors, returnees, and imprisoned cadres, this article will discuss the factors that motivated men and women to join ISIS, and how traditional gender roles and gender-based characteristics impacted their decisions. The article will further discuss the roles and experiences of men and women under ISIS, especially in the context of sexual and gender-based violence. Finally, the article will examine the interviewees’ sources of disillusionment with ISIS and the impact of gender on their changing opinions of the group.

METHOD (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020b)

The present article is a study which utilizes the interview data from a larger, open-ended research project aimed at understanding the vulnerabilities, motivations, influences, roles, experiences, and sources of disillusionment of male and female ISIS members. The project is also aimed at developing counter narrative materials and trainings for preventing and countering militant jihadist violent extremism. For the present study, the authors endeavored to answer the following research questions:

- How did gender broadly, and gender roles in particular, impact men’s and women’s decisions to join ISIS, and later, to leave ISIS?

- Did men and women differ in their motivations to join ISIS and their experiences within the group?

- Did the impact of gender present differently among men and women who were already living in Iraq and Syria at the time that they joined ISIS, as compared to those who were living elsewhere?

Participants

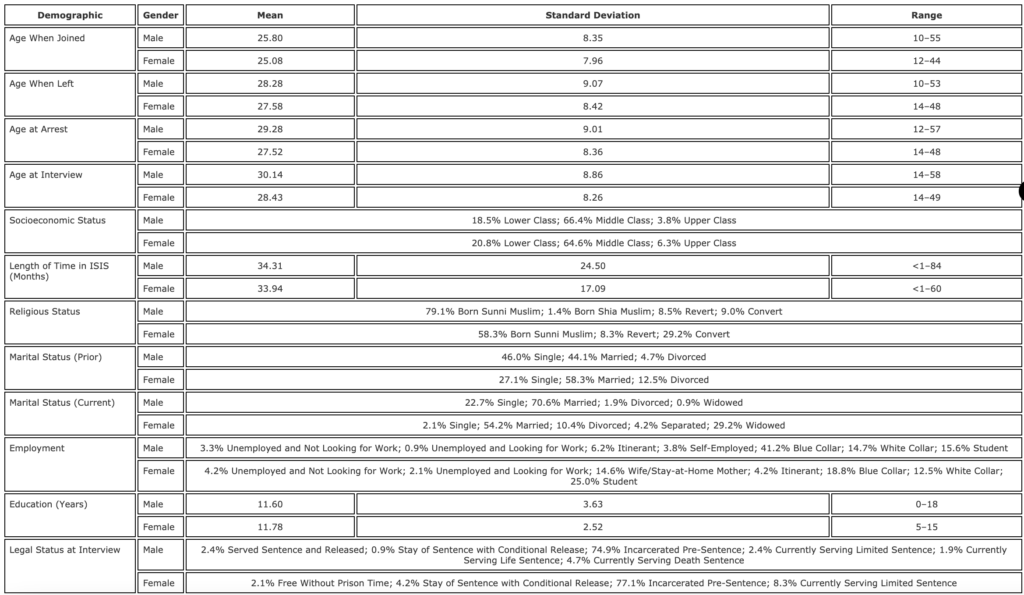

The participants included in the data analysis are 259 ISIS returnees, defectors, and imprisoned cadres, 211 of whom are male and 48 of whom are female. The participants were from 46 different countries, including 89 men and 9 women from Iraq and Syria (henceforth referred to as “locals”), six men from other Middle Eastern countries, 11 men and one woman from North Africa, one woman from the Horn of Africa, eight men and two women from Russia and Ukraine, two men and two women from central Asia, six men and five women from Southeast Asia, 86 men and 27 women from Western countries, and three men and one woman from the Caribbean. Those not from Iraq or Syria are referred to in this study as “foreigners.” Not all of the foreigners are FTFs, as two acted as recruiters from ISIS from their home countries, and five were stopped before entering Syria. Moreover, one participant who was born in Iraq and one who was born in Syria are considered foreigners in this study, as they were legal residents of the foreign countries from which they traveled to join ISIS. The participants were of 53 different ethnicities. A full demographic description of the sample is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Results

Recruitment Method

The research method for this study was to attempt to gain access to any member of ISIS, and to then conduct a semi-structured, video-recorded, in-depth psychological interview with that ISIS member. The lead researcher worked with prison officials, fixers, translators and research associates that arranged access to, video recorded, and translated the interviews and in six cases carried out the interview in the researcher’s absence, in one case due to the ISIS cadre arriving unannounced, in the second due to the interviewee refusing to talk to a woman and in the last four due to the COVID-19 pandemic and technical difficulties in a video link-up.

The sample for this study is by necessity a convenience sample, given the difficulty of gaining safe access to ISIS cadres to interview and to obtain their informed consent for an in-depth interview; thus, random sampling is not possible. The first author, interviewer, attempted to obtain a representative sample in terms of requesting access to women as well as men and attempting to talk to a wide range of nationalities and ethnicities, age groups and roles fulfilled within ISIS.

Interview Procedure and Ethical Considerations

The authors of this study are associated with an independent, nonprofit think tank with its own internal Institutional Review Board [IRB] modeled after the first author’s previous experience with the RAND Corporation’s IRB. In all cases, the semi-structured interview started with an informed consent process followed by a brief history of the interviewee focusing on early childhood and upbringing and covering life experiences prior to becoming interested in ISIS. Demographic details were gleaned during this portion of the interview, as were vulnerabilities that may have impacted the individual’s decision to join ISIS. Questions then turned to how the individual learned about the conflicts in Syria, and about ISIS, and became interested to travel and/or join, as not all of the interviewees actually traveled to live under ISIS; a few acted as recruiters at home. Questions explored the various motivations for joining and obtained a detailed recruitment history: How the individual interacted with ISIS prior to joining, whether recruitment took place in-person or over the Internet, or both; how travel was arranged and occurred; ISIS intake procedures and experiences with other militant or terrorist groups prior to joining ISIS; and training and indoctrination. The interview then turned to the interviewee’s experiences in ISIS: Family, living and work experiences including fighting and job history; inquiry about both positive and negative aspects of the individual’s experience in ISIS; questions about disillusionment and doubts; traumatic experiences; experiences and knowledge about one’s own or others attempts to escape; being, or witnessing others, being punished or tortured; imprisonments; owning slaves; treatment of women, and marriages. The interview covered where the individual worked and lived during his or her time in ISIS and changes over time in orientation to the group and its ideology, often from highly endorsing it to wanting to leave. The semi-structured nature of the interview ensured that participants were asked the same questions about their emotional states throughout their trajectories into and out of terrorism, regardless of gender. Moreover, the interviewer found that all interviewees, including the men, found it easy to express themselves emotionally when in the presence of a non-judgmental female psychologist.

In accordance with American Psychological Association [APA] guidelines and United States legal standards, a strict human subjects protocol was followed in which the researchers introduced themselves and the project, explained the goals of learning about ISIS, and that the interview would be video recorded with the additional goal of using this video-recorded material of anyone willing to denounce the group to later create short counter narratives videos. This is a project that uses insider testimonies denouncing ISIS as unIslamic, corrupt and overly brutal to disrupt ISIS’s online and face-to-face recruitment and to delegitimize the group and its ideology. The subjects were warned not to incriminate themselves and to refrain from speaking about crimes they had not already confessed to the authorities, but rather to speak about what they had witnessed inside ISIS. Likewise, subjects were told they could refuse to answer any questions, end the interview at any point, and could have their faces blurred and names changed on the counter narrative video if they agreed to it. Prisoners are considered a vulnerable population of research subjects, so careful precautions were taken to ensure that prisoners were not coerced into participating in the research and that there were no repercussions for not participating, either. The interviewer also made clear to the participants that she was not an attorney or country official and could not provide them with legal advice or assistance regarding their situation.

Risks to the subjects included being harmed by ISIS members for denouncing the group, although for those who judged it a significant risk, the researchers agreed to change their names and blur their faces and leave out identifying details. Likewise, there were risks of becoming emotionally distraught during the interview, but this was mitigated by having the interview conducted by an experienced psychologist who slowed things down and offered support when discussing emotionally fraught subjects. The rewards of participating for the subjects were primarily to protect others from undergoing a similar negative experience with ISIS and having the opportunity to sort through many of their motivations, vulnerabilities and experiences in the group with a compassionate psychologist over the course of an hour or more. The majority of interviewees thanked the researcher for the interview.

Statistical Analyses

The results presented in this article are both qualitative and quantitative. The researchers used the interviewer’s notes, transcribed interviews, and videoed interviews to code the interviews on 342 variables in SPSS Statistics Version 26. The coding scheme was developed by the authors using the interview questions decided upon a priori as well as themes identified from the interviews. The variables related to the participants’ demographic information, life experiences, motivations and influences for joining ISIS, travel to Syria or Iraq if applicable, roles and experiences in the group, sources of disillusionment with the group, and present feelings about the group and the participants’ actions within the group. The second author coded the interviews on 342 variables and conducted the data analysis for this article in SPSS. Although personnel limitations precluded a full measure of inter-rater reliability, the second author regularly consulted with the first author whenever a code was in question to receive a second opinion.

The statistical analyses conducted in this article consist of descriptive statistics and chi square tests to detect statistically significant differences between men and women generally as well as differences between foreign men and foreign women, and local men and local women. Chi square tests were calculated based on whether or not the interviewee reported experiencing the specific event, feeling, or motivation when prompted during the interview, or whether they mentioned the event, feeling, or motivation spontaneously. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics Version 26.

This article also utilizes qualitative analyses. Content analysis involved using SPSS Statistics Version 26 to identify which interviewees mentioned the subject matter of interest, and then gleaning direct quotations from those interviews regarding the subject matter. Those quotes were analyzed regarding their emotional salience and the level of impact that the various vulnerabilities, influences, and motivations had on the interviewee’s decision to join ISIS, and the level of impact that the various sources of disillusionment had on the interviewee’s decision to leave ISIS.

RESULTS

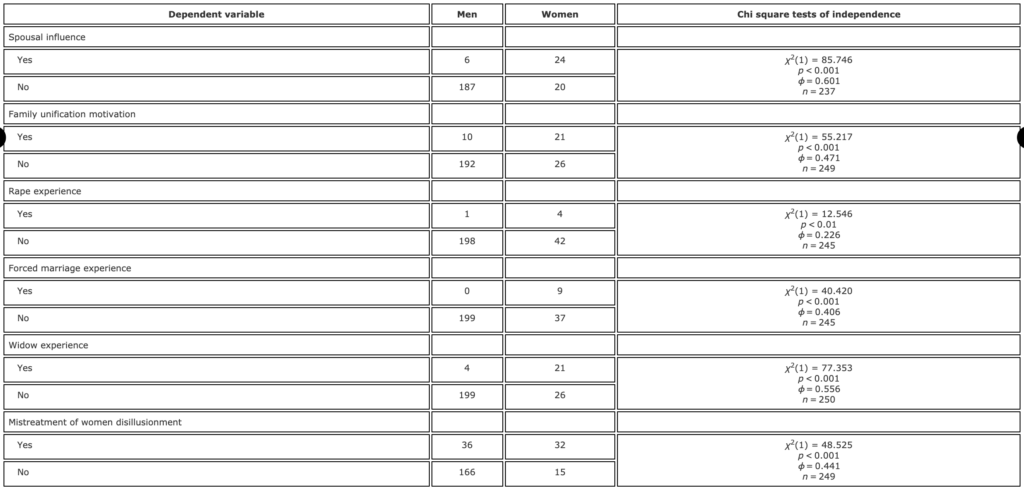

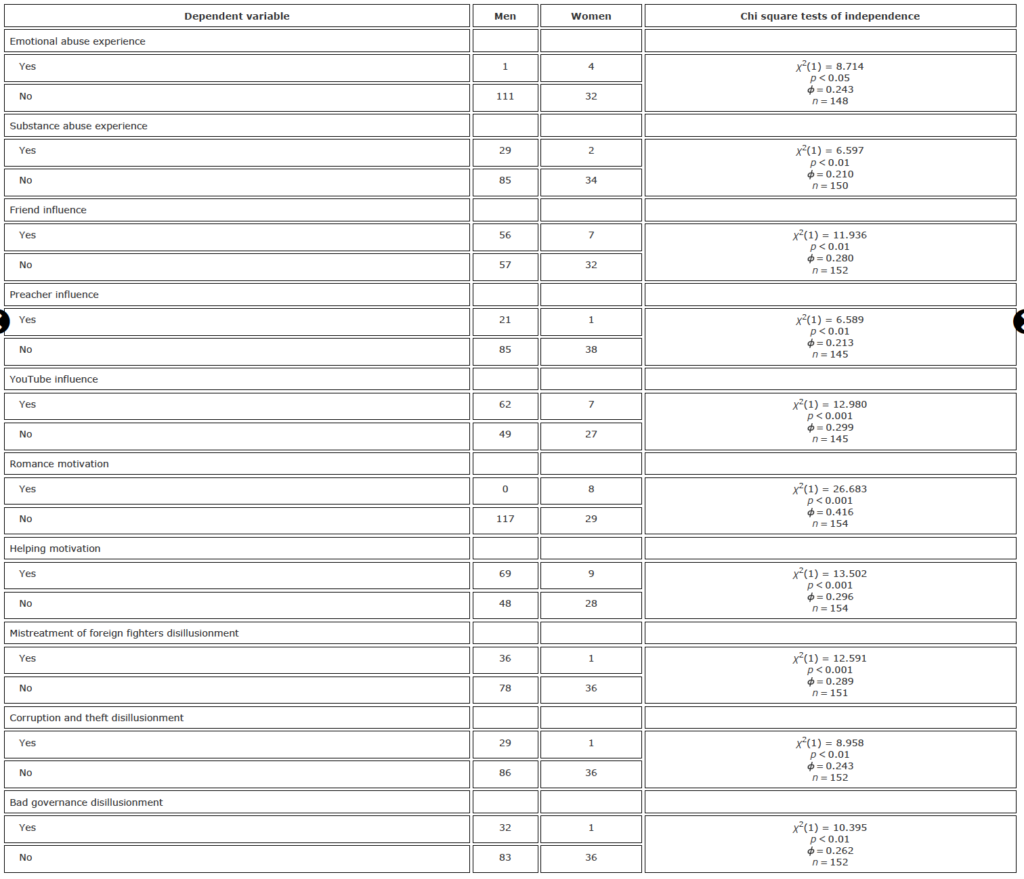

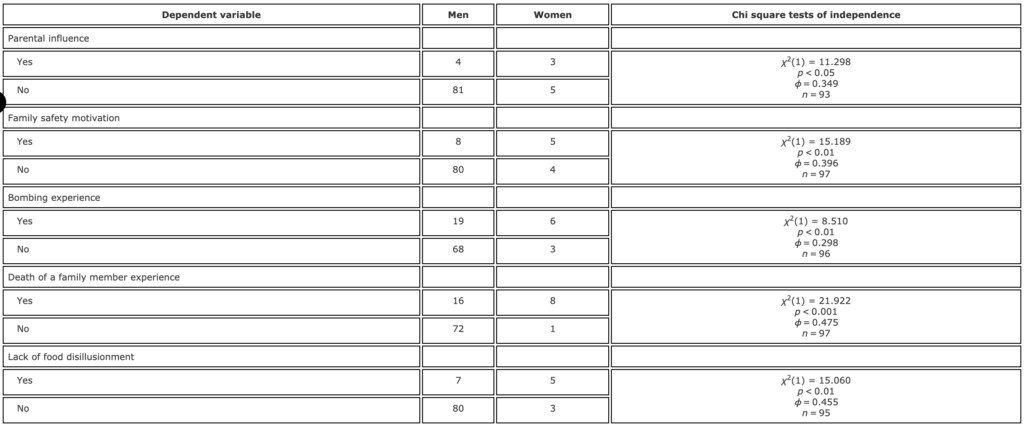

In this section, quantitative and qualitative results pertaining to gender differences in vulnerabilities, influences, motivations, experiences in ISIS, and sources of disillusionment. Many of the differences are significant only between foreign men and foreign women or local men and local women or are significant only when the entire sample is aggregated but not when disaggregated by whether or not the participants originated in Iraq and Syria. Table 2 presents the most meaningful results, that is, those that are significant on the aggregate as well as when disaggregated between foreigners and locals. These results are illustrated in more detail in the forthcoming subsections. Table 3 presents the results that were significant only among foreigners and Table 4 presents the results that were significant only among local ISIS members.

Table 2. Chi square results significant across locals and foreigners

Table 3. Chi square results significant only for foreigners

Table 4. Chi square results significant only for locals

Vulnerabilities, Influences, and Motivations to Join ISIS

With regard to their vulnerabilities toward radicalization, men and women differed significantly on a myriad of variables, although the gender differences also differed between foreign members of ISIS and those from Iraq and Syria. This is unsurprising, given the overall differences in foreigners’ and locals’ motivations for joining ISIS and their experiences within the group (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020b). Across the entire sample, women were more likely than men to report experiencing emotional abuse in the past (χ2 = 13.26, p<0.01). This is consistent with prior research showing that female criminal offenders are more likely to have histories of childhood maltreatment than male offenders (Fagan, 2001). When broken up between foreigners and locals, only foreign women were more likely than foreign men to have experienced emotional abuse (χ2 = 8.71, p<0.05). Across the entire sample, men were more likely than women to report experiencing unemployment or under-employment (χ2 = 5.87, p<0.05). These results are unsurprising given that while in general men are not more likely to be unemployed than women, the traditional expectation for men to provide for their families means that they may be more deeply affected by unemployment than women, whereas women may be more affected by their perception of themselves and their role within the family unit (Shamir, 1985; Artazcoz et al., 2004). This difference was not evident when the sample was broken up between foreigners and locals. Finally, foreign men were more likely than foreign women to have a history of substance abuse (χ2 = 6.60, p<0.05). This is consistent with prevalence rates in the general population (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Interviewees were also asked about their influences toward joining ISIS. Both local and foreign women were more likely than local and foreign men to report being influenced by their spouses and partners (aggregated: χ2 = 85.75, p<0.001), and local women were also more likely than local men to be influenced by their parents (χ2 = 11.30, p<0.05). Foreign men were more likely than foreign women to report being influenced by friends (χ2 = 11.94, p<0.01), preachers (χ2 = 6.59, p<0.01), and YouTube (χ2 = 12.98, p<0.001). These results mirror the motivational results discussed in the coming paragraphs, which similarly support an increased importance of the role of the family unit for women.

With regard to the participants’ motivations for joining ISIS, none explicitly stated that they were directly motivated by a desire for sex, but their other expressed motivations reflected the draw of traditional gender roles and the attraction of the hyper-masculine portrayal of ISIS men. Eight men stated that they were motivated by the prospect of adventure, and one woman said the same. In contrast, eight women stated that they were motivated by the prospect of romance, and only one man said the same. This reflects ISIS’s targeted recruitment, tailoring their message to best attract men who feel emasculated or helpless and women who did not support Western manifestations of gender equality and who wished to live traditional lives as wives and mothers. Furthermore, four men and two women stated that they joined ISIS to take on traditional gendered stereotypical roles as defined by Islam and ISIS, with the man as the protector and head of the home and the woman as the heart of the home functioning as wife and mother, thereby enhancing their masculine and feminine identities, respectively. One of the four men who desired to establish a masculine identity by joining ISIS also stated that he was also motivated by a desire for adventure. Both of the women who desired to establish a feminine identity also stated that they were motivated by romance.

Thirteen of the FTF males and one of the FTF females directly referenced being excited by the prospect of using weapons, as did four of the local males, though others admitted that there was a heady high to training with ISIS initially. Many local males appreciated the material benefits, especially the pay that came with joining ISIS that could make them function much better in traditional male roles as providers, with 40 of the local men (44.9 percent) citing either employment or meeting their basic needs as a motivation for joining the group. One young man was only 14 when he joined ISIS in Iraq. He explains the sense of adventure and boyish fun that convinced him to join: “They gave a training: Pushups, sit-ups, and how to use the gun. I like sport. I saw my friends carrying weapons on checkpoints, so I liked that idea.” Abu Ridwan al Canadia, aged 36, maintained the same goal: “I wanted action.” Another Iraqi teenager acted as a spy for his older cousin in ISIS: “He paid me for each mission like a present […] It was fun, I used this money with my friends to café; buy something for myself. Sometimes I would go on trips with this money.” The two Iraqi boys demonstrate the different types of masculine norms that attracted ISIS members. While one wanted to be a warrior, the other wanted to be a provider, neither of which would have been possible had they stayed home as ISIS overtook their towns. Abu Ayad, a 20-year-old Iraqi, expressed a similar sentiment. When he watched ISIS’s videos on Twitter and Facebook, he says, “They affected me because I was poor. I wanted to improve my condition [for] marriage. I wanted us to have a house and for me to get married, and to have money.” Iraqi Ibn Faisal felt the same. He recalls joining ISIS as a 16-year-old. He and his friends saw ISIS quickly take over Mosul and thought “we never saw people like this before, where they came from it was amazing, felt they are very powerful, they can invade all of Iraq. They said everyone who joins us we will give him a share of money we control and cars.”

Many ISIS men felt a sense of honor in volunteering themselves in a warrior and protector role, seeing themselves as heroic and faithful to Islam by doing so. This sense of honor manifested in a myriad of motivations: Helping the Syrian people (n=71), fulfilling their obligation to wage jihad (n=39), fighting for justice on behalf of the Syrian people (n=28), and feeling personally significant (n=19). A Danish fighter who was recruited by a family member remembers being told, “We are making jihad and here to help. You give Muslims honor and […] you’d be a hero.” Libyan Abu Musrata concurs, recounting his hope to emulate the Libyan Arab Spring in Syria: “I didn’t used to think about Khalifa; my thought was to come to get rid of the regime of Assad, to get rid of him like we did Qaddafi. I didn’t fight in Libya; I was only 14.” He later explains that he had a friend from school who fought in Libya, saying, “He didn’t come [to school] on the regular days but he came for exams and we saw how the teachers treated him in a special way.” Asked if he too wanted to be a hero, Abu Musrata replies, “It is the ambition of every man […] I thought to myself if I do this, I will be a hero. If I go and defend those [Syrian] ladies, I will be a hero.” This view was common among male foreign fighters. Abu Musa al Brittani grew up in the United Kingdom and was radicalized by a teacher in Bangladesh. He explains, “When you’re young, you always think Islam is when you get older. You pray, you read the book, wait for death to come […] He came from a different direction, he made it heroic […] for example jihad, concepts of religion you never hear about before, military […] allegiance and loyalty.”

American-born Abu Fuad al Ameriki grew up in Saudi Arabia and was studying to be a doctor when he joined ISIS. Like the other foreign fighters quoted above, Abu Fuad sought excitement and adventure: “During my internship I focused on going to trauma centers, the kind of cases we were receiving, 90 percent were road traffic accidents, they were awful, but they were not like war injuries. War injuries are more awful; I wanted the experience, challenge, I want to see the cases in a hostile environment.” Although he did not state it explicitly, it is clear that Abu Fuad left for Syria not only looking for a challenge, but to be a hero, bringing his Saudi education and medical skills to the poor, desperate, and beleaguered Syrian victims of Assad.

Belgian Laura Passoni perhaps best describes the romance and feminine identity she hoped to develop in ISIS. Heartbroken at the end of a relationship in which the Muslim father of her young child was adulterous, Laura was searching for a partner who would keep his vows and be true to Islam and to their marriage. She met an ISIS recruiter online who seduced her with promises of an idealistic life in the Caliphate: “He said that women could be nurses and help the orphans. He said women had status there and were precious. We women could go to ISIS to enjoy Paradise there. He said I would have a villa, that I would have horses […] He said I would be rich, even with diamonds.” When she arrived in Syria, however, Laura learned the truth: “We women are just there to procreate […] We have nothing. We have no rights. We were prisoners there.”

Kenyan Aisha, a domestic worker in the United Emirates at the time of her online recruitment, was stopped on her way to join ISIS. The feminine identity she hoped to establish was one of heroic dominance rather than meek subservience. She remembers looking online and seeing “pictures of Islamic women, dressed all in black stockings and gloves and niqab and she was holding an AK-47 […] She was independent.” Aisha also was seduced by a man online with whom she fell in love: “He said he wanted to get married. We would go to Iraq and marry and fight together and go to Jannah together.” When Aisha decided to carry out a suicide mission, she was exhilarated by what she believed was her chance to act in a heroic role on behalf of Islam.

Beyond these more overtly gender-based motivations, men and women also differed significantly in their reports of other types of motivations for joining ISIS. Nevertheless, these motivations still reflect a gendered desire among the men to feel powerful and heroic, and a desire among the women to feel like valued members of a family. Across locals and foreigners, men were more likely to be motivated by employment (χ2 = 7.41, p<0.01) and a desire to fight for Sunni rights (χ2 = 5.22, p<0.05). Among the local interviewees, women were more likely than men to join ISIS in order to provide safety for their families (χ2 = 15.19, p<0.01). This was particularly true in areas that ISIS had overtaken. Among the foreigners, women were more likely to be motivated by romance (χ2 = 26.68, p<0.001), as mentioned above, and men were more likely to be motivated by a desire to help the Syrian people (χ2 = 13.50, p<0.001). Even when disaggregated, both local and foreign women were more likely than local and foreign men to be motivated by a desire to keep their families together (aggregated: χ2 = 55.22, p<0.001). For foreign women especially, this motivation was demonstrated when the women brought their children to join their husbands in Syria after their husbands threatened to divorce them or take a second wife in Syria. Said 23-year-old Belgian Cassandra of her husband, 26years her senior, “He started warning me that if I don’t come, he’s going to divorce me, take a second wife. That I cannot accept […] He came before me, and I was so touched, that he was here alone, then I follow.”

Experiences in ISIS

The interviewees’ roles in ISIS are consistent with other studies of men and women’s roles in the terrorist group. Whereas men held a variety of roles, from ribat (border patrol), to fighting, to being engineers, housing administrators, and members of the shurta (military police), women held fewer professional roles. All of the women in this sample acted as wives and mothers. Indeed, foreign women were not allowed to live on their own without marrying, and if arriving single or widowed, they were forced into ISIS guesthouses, madhafas, until a suitable marriage was arranged. Among roles other than wife and mother, one woman, who was apprehended before arriving in Syria, desired to become a suicide bomber. Two women, both locals, were members of the hisbah. One local woman also acted as an in-person recruiter for other women to join ISIS, and one foreign woman worked as a nurse in a hospital.

Umm Rashid, a 21-year-old Syrian woman, describes how her membership in ISIS’s hisbah, the morality police, allowed her to take back a power she felt she had lost when she was forced to drop out of school because of the war and a series of traumas occurred in which her first husband who joined al Nusra was killed and then her parents were killed by bombardments and her sister lost her arm. She recounts what she and her comrades would do if they caught a woman dressed in colors, which was forbidden in ISIS: “We would take off the clothes of the woman until she is in her underwear then we would beat her with a lash and then there are special women in the hisbah for biting and they would bite that woman, so we would torture that woman so badly that […] she wouldn’t be able to walk.” If the woman repeated her offense, Umm Rashid explains, “We would take the husband and put him in a football field where the coalition forces used to bomb a lot. We had a prison, and we would put him in that prison. Most of the time he would die of fear because of the explosions in that field.” When asked if she found it hard to “bite” other women, Umm Rashid said that to the contrary, acting aggressively toward others and forcing them to comply with ISIS rules made her feel powerful and safe and helped her face down her fears from all the traumas she had endured. Asked if she has any regrets, Umm Rashid replies, “I would do the same thing again if given the opportunity. I escaped because I have a small child; I want to go back after the baby is grown. They are seducing young men with those colorful abayas” (Speckhard & Yayla, 2017a, 2017b).

Gender-Based Violence in ISIS

The interviewees spoke about their experiences in ISIS, as victims, witnesses, and perpetrators of traumatic events. While their specific experiences differed, both men and women experienced extreme violence during their time in ISIS. Both foreign and local women were significantly more likely than males to have been raped (aggregated: χ2 = 12.55, p<0.01), to have been forced into marriage while under ISIS (aggregated: χ2 = 40.42, p<0.001), and to have been widowed while in ISIS (aggregated: χ2 = 77.93, p<0.001). Four women reported surviving rapes while in ISIS. Nine women reported being forced into marriage. One of these women also stated that she had been raped by her ISIS husband. Given that many women did not define marital sex with husbands they were forced to marry as rape, it is possible that eight additional women had also been raped, albeit by their husbands (Martin et al., 2007). Five men reported witnessing rapes. Three of the men were acting guards at the prisons where ISIS held sex slaves—mostly captive Yazidi women, but also Shia, Christian, and Sunni women whose husbands had been captured and killed by ISIS. Another man witnessed his emir rape a young boy and was also raped by the same emir. One man discussed raping 50 different captured women individually, over a long period of time, who were held in an ISIS guest house for that purpose. An ISIS emir also referred to raping captured women as well but stated that he did not himself own sabaya (captured women forced into sexual slavery). Instead, he claimed that captured women were the property of the Islamic State. As he explains, “It becomes a right, if I dominate everything in my room, it becomes mine; I do as I want.” Another man admitted owning Christian and Yazidi sabaya, while others spoke about being encouraged to take a captured woman as their sex slave.

Canadian Kimberly Pullman already had a history of sexual abuse when she joined her online husband in Syria. She hoped that joining ISIS would give her an opportunity to restore her honor, but she was instead subjected to the same sexual violence that she had experienced at home with ISIS men she encountered in Syria. She recounts, “They threw me in prison for inquiring about how to leave. [I was] raped again in prison […] The first night they pulled me out and you could hear the screams down the hallway […] I could see men in all different stress positions […] I came out with a massive concussion.”

Ibn Ahmed, a Syrian defector who was 19 at the time of his interview, told of the incidents that led him to decide to leave ISIS. After seeing a woman taken away from her nursing baby to be raped, he witnessed a Sudanese foreign fighter commit an unthinkable act:

That [foreign fighter] was very tall, a big [guy], had taken a girl who was fifteen. He raped this girl. I swear to God she was hemorrhaging so he brought her back to the prison. They got an ambulance and took her out. They told the guys [that] these are captives, and you can do whatever you want with them. So, after this girl had a hemorrhage, she died of internal bleeding. Our commander forbade us to talk to anyone about it […] After this one died, the shariah court sent for the [foreign fighter] and put him in jail. I wanted to see how they were going to punish him. So, I continued to work for a week. But they pardoned him after seven days and he was back to his post.

A majority (58.3 percent) of the women lived, at least once, in the filthy, overcrowded guest houses, madhafas, that ISIS arranged for unaccompanied women, with nine of the women living in one for two different periods of time and four women living in one for three different periods of time. All of the women who lived in a madhafa were foreigners. Six women reported that they lived in madhafas as widows, leading them to quickly remarry in order to escape the horrid conditions. Irish Lisa Smith describes her months long experience in a madhafa, run by another woman, demonstrating the desire to subjugate their sisters in faith that some ISIS women demonstrated, perhaps due to their sudden found power and choice within the ISIS society. Lisa Smith recalls of the woman, “She’s a psychopath, she turned this madhafa into a prison […] You had to stamp with your finger and sign it for every single thing you ate, even a tomato, you could not get out of the madhafa ever […] you had to pee and eat in that room, she’d beat them.”

Beyond the sexual violence, local women were also significantly more likely than local men to report experiencing bombardments (χ2 = 8.51, p<0.01). Local women were also more likely than local men to report having a family member die in an ISIS-related incident such as violence, bombings, or starvation (χ2 = 21.92, p<0.001). Across locals and foreigners, men were more likely than women to have witnessed an execution (χ2 = 5.98, p<0.05), but this difference was not seen in the sample when disaggregated between foreigners and locals.

Sources of Disillusionment

Finally, the interviewees’ sources of disillusionment differed by gender and between locals and foreigners. In fact, the only source of disillusionment that affected both local women and foreign women significantly more than local and foreign men was ISIS’s mistreatment of women (aggregated: χ2 = 48.53, p<0.001). Among the foreigners, men were more likely than women to say they were disillusioned by ISIS’s mistreatment of foreign fighters (χ2 = 12.59, p<0.001), corruption and theft (χ2 = 8.96, p<0.01), and bad governance (χ2 = 10.40, p<0.01). Local women were more likely than local men to report being disillusioned by lack of food (χ2 = 19.69, p<0.001).

There was no significant gender difference regarding disillusionment with ISIS’s attacks outside of its territory. Rather, these attacks served as a source of disillusionment for men and women alike, particularly those from Europe, where ISIS committed a number of high-profile attacks. Five European women (20.0 percent) and 17 European men (23.0 percent) were disillusioned by ISIS’s attacks on their home countries and killing innocent civilians back home in these attacks. Salma, a 22-year-old Belgian woman was one who was extremely disillusioned by ISIS after following her Tunisian Belgian father there in the hopes of living a pure Islamic life. Of ISIS attacking outside of their territory, specifically the 2016 bombings at the Zaventem airport in Brussels, she says, “Killing people on the battlefield, they have guns shooting at you. If you kill him, ok, you’re defending yourself. But killing people who are innocent, they don’t have anything. They’re just going there. It could have been me there.” She continues, “What did I do? Did I send the alliance [to Syria]? Did I say to Belgium, ‘go bomb people’? No. Most people in Belgium don’t even know. They don’t really follow [the news] that Belgium allied to kill ISIS.”

DISCUSSION

This article addresses the dearth of primary data in the study of gender and ISIS by providing extensive qualitative accounts of men and women’s trajectories into and out of ISIS. The information presented in this article provides clear future directions for preventing radicalization to violent extremism among men and women, particularly in Western countries. If and when ISIS FTFs are repatriated, these gendered aspects of their experiences must be addressed in efforts to rehabilitate them and reintegrate them into society. Both women and men were enticed by ISIS’s promise of traditional gender roles. Some women in Western societies who joined ISIS felt restrained and discriminated against at home for their choice to adhere to strict gender roles and conservative Islamic dress. Under the Caliphate, they believed they would be celebrated and honored as wives and mothers, under no pressure to work outside the home, interact with strange men, or dress in a way that made them uncomfortable. Some ISIS men also commented on these issues, particularly their wives being spat at or cursed when wearing niqab (the full Islamic face covering). Similarly, ISIS was able to recruit thousands of disaffected, alienated, and marginalized young men to their ranks, many of them from Western Europe, by portraying ISIS men as warriors and heroes, leaders of their families. Many of the men who joined ISIS from Western countries were first- and second-generation Muslim immigrants who had grown up with strict gender roles and traditional families or who had embraced a more conservative practice of Islam as a means of seeking their identity after growing up in more permissive circumstances. Both groups found observing conservative practices of Islam in Europe challenging. Some may have also felt emasculated by the Western notion of shared responsibility in the home as well as their perceived humiliation if they were not able to be the primary breadwinner for their families, making the ISIS Caliphate’s claim of idealized traditional gender roles and values alluring (Necef, 2016). Many of these immigrant descent Muslim men in Europe were also finding their paths to the more traditional masculine role of being the breadwinner stymied by discrimination and marginalization and were struggling with the humiliation of being unemployed or underemployed (Hansen, 2012). Similarly, in other parts of the world, economic tumult and corruption played a role for men (Sika, 2021). For instance, Tunisian men struggling with unemployment and the resultant inability to marry found the ISIS promises of paid jobs, provided housing, and marriage similarly attractive alongside the honors of knowing they could play the “man of the house” role in ISIS.

It should also be noted that ISIS played out to the strict conservative Islamic values about sexuality and honor that are pervasive in the region, expanding upon the honor-based society present in many Middle Eastern and North African cultures. In honor-based societies, family and tribal honor is considered to be upheld by the virtue of the females, and males are called upon to guard the virginity and honor of their females and to strongly punish those who do not comply. In such societies, gender separation is often practiced, modest dress and covering is required, and women are protected in the home as well as carefully chaperoned when outside the home (Cihangir, 2013). While these are the norms for some throughout the region, ISIS amplified these practices to the extreme and used brutal violence to enforce them.

As is clear from scores of reports on ISIS, hyper-masculinity and misogyny were on full display in the Caliphate, not only in their portrayal of men heroically fighting to free the beleaguered victims of Assad while building up the ISIS Caliphate as hyper-masculine acts, but also in their blatant promotion of sexual violence. Sexual violence against and the enslavement of Yazidi, Shia, and other women, including Sunni wives of Syrian regime soldiers, reinforced ISIS’s superiority and domination of other groups in the area through dominating their women (Ahram, 2015). Like gangs and other criminal organizations, ISIS also viewed captured women as commodities, gleaning a significant source of their revenue through human trafficking (Levitt, 2014).

ISIS’s propensity toward sexual and gender-based violence is demonstrated quantitatively and qualitatively in this study, wherein both ISIS women and men describe rapes, forced marriages, and domestic violence. One man also reported being raped, and another to knowing about a male youth being raped, a practice that, although highly underreported, is not uncommon in hyper-masculine conflict settings. According to Ahram (2015), “this type of violence is, in some respects, the ultimate act of humiliating de-masculinization.” The same is true for male and female victims of rape: Sexual attraction is not part of the equation. Thus, ISIS’s brutal treatment and sexual violence toward male and female rape victims was first and foremost to exert power and control and to take what were claimed as the rewards of the hypermasculine warrior, hence reinforcing this stereotype as the ideal. ISIS’s brutal treatment of homosexual men and stoning of women who they claimed to be adulterous also is not incongruent with their practice of sexual violence, as these practices also reinforced rigid rules regarding gender roles, gender separation and sexuality (Ahram, 2015).

This study provides significant insight into the psychological and physical experiences of foreign and local members of ISIS through the lens of gender. As gender roles and the very definition of gender expand and develop in liberal democracies, ISIS presented itself not only as a true Islamic Caliphate but as a bastion of traditional and strict masculine and feminine identities and as a utopic place to live out these values. It is evident that seeking to take on these masculine and feminine identities, such as warrior, hero, and protector for men and protected wife and mother ensconced in the home for women, and their associated characteristics, such as hypermasculinity and dominance for men and traditionalism and modesty for women were a driving force for many of the interviewees to join the Caliphate.

Limitations

As previously mentioned, the lack of a random, representative sample is a limitation of this study, albeit an unavoidable one. Other limitations include the chance that participants did not answer completely honestly, either due to a desirability bias or to the presence of prison guards or minders in the interview rooms, and the variation in interview length, or discomfort in the prison setting. The dearth in primary data in terrorism research can be linked to the difficult nature and impediments in the interview process with incarcerated people, thus, these limitations may be considered the cost of obtaining the data. Additionally, the uneven numbers of men and women present a limitation for the chi square tests, despite the proportion of women in the sample being reflective of the proportion of women who joined ISIS as compared with men. Including more women in the sample would make the results more accurate and valid.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Paradoxically, ISIS’s brutality in enforcing these traditional gender identities and their failure to deliver on their promises of creating an Islamic utopia where they could be lived out caused many of these same individuals to become deeply disillusioned with the group. Many of the interviewees have become disillusioned and have begun the process of “spontaneous deradicalization,” which is the subject of a related report on the same data set (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020a). Nevertheless, the vulnerabilities, needs, and desires that drove them to ISIS often still exist. There are still many places in the world where men struggle to self-actualize to what they view as positive masculine identities due to discrimination, marginalization, and un- and underemployment. Similarly, many Muslims living in the West, particularly women who prefer to dress conservatively, some donning black burkas and niqab, face serious Islamophobic discrimination and harassment for doing so (Zempi, 2014). Likewise, for conservative Muslims, the many choices of liberal society, the advertising, television, movies, public behavior, and attire are an assault to their values and can cause anxiety and a desire to seek out more rigid, gender-conforming societies where life is more clearly defined in binary terms.

ISIS men and women incarcerated either in prisons or camps run by the SDF may also have developed new vulnerabilities that need to be addressed if and when they are repatriated by their home countries. For instance, ISIS foreign male and female prisoners often complain that they know their home countries do not want them back, and even if they are repatriated, prosecuted, and serve time in prison, they fear that they will never get jobs and will always be labeled as terrorists, no matter how repentant and rehabilitated they may become. For men, unemployment was a major source of vulnerability to joining ISIS, which can be subsequently tied to a desire to feel purposeful, significant, and important. If and when these men are repatriated, many of them will receive limited prison sentences in their home countries which may mean they will carry a criminal record, making it hard to later find employment. Rehabilitation and reintegration programs will therefore need to address providing these men with prosocial mechanisms for coping with stress as well as the skills to gain employment and to build fruitful lives. ISIS wives who want to work outside their homes will face similar challenges if they are ever able to return to their home countries. For both, the social stigma and long-term labeling will need to be addressed, as both can make it hard to ever find employment and rebuild their lives.

Furthermore, foreign men in the prisons and women held in the SDF camps have experienced extreme trauma and are also at risk of being separated from their children if their countries refuse to repatriate the adults or take only the women and children. ISIS women in the camps face brutal and violent ISIS enforcers, difficulties obtaining nutritious food for themselves and their children and threats of disease on a daily basis. Prior trauma was also a significant vulnerability for local women as opposed to local men, and familial safety was a significant motivation for local women to join ISIS, as well as forced marriages to ISIS men. Local women and foreign women alike were also highly motivated by a desire to keep their families together, making them vulnerable to recruitment by new groups who promise to help them keep their families together when they are in danger of being torn apart. Already, there is evidence of many women getting smuggled with their children out of Camp al Hol in Northeast Syria, some to rejoin ISIS or other militant jihadists in Idlib. Women in particular, but ISIS men as well, will likely need serious and effective posttraumatic stress counseling to deal with all that they witnessed and experienced inside ISIS, and also what many endured while detained without charges (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020b).

As the global community considers future directions for dealing with the thousands of men, women, and children waiting in legal limbo in SDF territory, policymakers and practitioners must consider the gender perspective when addressing potential returnees. Doing so will require not only considering sexual and gender-based violence and the experiences of women, but rather considering the ways in which gender can inform men and women’s journeys into and back out of ISIS and other similar-minded groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to the Syrian Democratic Forces, Abu Ali and the Iraqi Falcons Intelligence Cell, Iraqi Counter Terrorism Services, the Aarhaus Police, the Kurdish Asayish, the Kosovo Prison Services, the Albanian Justice and Prison Ministries, Kenyan National Counter Terrorism Centre, Ahmet Yayla, Ardian Shajkovci, Haris Fazilu, Vera Kilmani, Skender Perteshi, Rudy Vranx, Hogir Hemo, Osama, Mohamed, and many others not mentioned here who helped facilitate, arrange, translate and film these interviews.

Additional information

Funding

The present research was financially supported by European Commission; Embassy of Qatar in Washington, DC.

Reference for this article: Speckhard, Anne, and Ellenberg, Molly (2021). ISIS and the Allure of Traditional Gender Roles. Women & Criminal Justice. https://doi.org/10.1080/08974454.2021.1962478

About the Authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D., is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 700 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past five years years, she has in-depth psychologically interviewed over 250 ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners as well as 16 al Shabaab cadres (and also interviewed their family members as well as ideologues) studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS (and al Shabaab), as well as developing the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project materials from these interviews which includes over 250 short counter narrative videos of terrorists denouncing their groups as un-Islamic, corrupt and brutal which have been used in over 150 Facebook and Instagram campaigns globally. Since 2020 she has also launched the ICSVE Escape Hate Counter Narrative Project interviewing 25 white supremacists and members of hate groups developing counternarratives from their interviews as well. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals, both locally and internationally, on the psychology of terrorism, the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS. Dr. Speckhard has given consultations and police trainings to U.S., German, UK, Dutch, Austrian, Swiss, Belgian, Danish, Iraqi, Jordanian and Thai national police and security officials, among others, as well as trainings to elite hostage negotiation teams. She also consults to foreign governments on issues of terrorist prevention and interventions and repatriation and rehabilitation of ISIS foreign fighters, wives and children. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, the EU Commission and EU Parliament, European and other foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA, and FBI and appeared on CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, CBC and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly writes a column for Homeland Security Today and speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her research has also been published in Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Journal of African Security, Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, Bidhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, Journal for Deradicalization, Perspectives on Terrorism and the International Studies Journal to name a few. Her academic publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhardWebsite: and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Molly Ellenberg is a research fellow at the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE]. Molly is a doctoral student in social psychology at the University of Maryland. She holds an M.A. in Forensic Psychology from The George Washington University and a B.S. in Psychology with a Specialization in Clinical Psychology from UC San Diego. At ICSVE, she is working on coding and analyzing the data from ICSVE’s qualitative research interviews of ISIS and al Shabaab terrorists, as well as white supremacists, members of hate groups and conspiracy theorists; running Facebook campaigns to disrupt ISIS’s and al Shabaab’s online and face-to-face recruitment; and developing and giving trainings for use with the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos. Molly has presented original research at the International Summit on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma, the GCTC International Counter Terrorism Conference, UC San Diego Research Conferences, and for security professionals in the European Union. She is also an inaugural member of the UNAOC’s first youth consultation for preventing violent extremism through sport. Her research has also been published in Psychological Inquiry, Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, AJOB Neuroscience, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, the Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, Bidhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, and the International Studies Journal. Her previous research experiences include positions at Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.

REFERENCES

- Ahram, A. I. (2015). Sexual violence and the making of ISIS. Survival, 57(3), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2015.1047251 [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. (2015). ISIS and propaganda: How ISIS exploits women. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/research/files/Isis%2520and%2520Propaganda-%2520How%2520Isis%2520Exploits%2520Women.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Almohammad, A. H., & Speckhard, A. (2017). The operational ranks and roles of female ISIS operatives: From assassins and morality police to spies and suicide bombers. ICSVE Research Reports. https://www.icsve.org/the-operational-ranks-and-roles-of-female-isis-operatives-from-assassins-and-morality-police-to-spies-and-suicide-bombers/ [Google Scholar]

- Amar, P. (2011). Middle East masculinity studies: Discourses of “men in crisis,” industries of gender in revolution. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 7(3), 36–70. https://doi.org/10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.7.3.36 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Artazcoz, L., Benach, J., Borrell, C., & Cortes, I. (2004). Unemployment and mental health: Understanding the interactions among gender, family roles, and social class. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.1.82 [Crossref], [PubMed], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Asal, V., Legault, R., Szekely, O., & Wilkenfeld, J. (2013). Gender ideologies and forms of contentious mobilization in the Middle East. Journal of Peace Research, 50(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313476528 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, M. (2012). Gender-based explosions: The nexus between Muslim masculinities, jihadist Islamism and terrorism. UNU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, M., Sutcliffe, J., & Lee, M. (2019). Framing the ‘White Widow’: Using intersectionality to uncover complex representations of female terrorism in news media. Media, War & Conflict, 12(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635218769931 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, M. (2011). Bombshells: Women and terror. Gender Issues, 28(1–2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-011-9098-z [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, D. (2016). Gendering ISIS and mapping the role of women. Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 3(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347798916638214 [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Cihangir, S. (2013). Gender specific honor codes and cultural change. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212463453 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J., & Vale, G. A. (2018). From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’: Tracing the women and minors of Islamic State. International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. [Google Scholar]