Islamist Extremism in the U.S. Getting a Closer Look

Voice of America article quoting ICSVE Director Anne Speckhard, Ph.D.

By Jeff Swicord

June 13, 2016

WASHINGTON —

This is the first article in a three-part series on Islamist Extremism in America.

One day after the worst mass-shooting in U.S. history, this was known about the killer: he supported Islamic State but had no known direct ties; he expressed hatred of gays; his ex-wife accused him of being abusive; and he earlier claimed ties to al-Qaida, prompting the FBI to question him at least twice.

Omar Marteen was also a Muslim, a father, a son of middle-class Afghan immigrants, a security guard for nearly a decade and the owner of a state-issued firearms license.

The question some are asking is which of the above factors provides a key to why Marteen walked alone into a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, early Sunday and killed 49 people.

Flood of information after attacks

In a non-descript office in a shopping mall on the edge of the campus of George Washington University in Washington, D.C., researchers log the tweets of English-speaking Islamic State (IS) supporters worldwide. The Center for Cyber and Homeland Security is one of many centers for the study of extremism cropping up across the U.S.

“There is a really big swell of information that comes right after attacks,” says research fellow Audrey Alexander, who, along with her colleagues, follow more than 1700 English speaking accounts – 300 of them in the U.S.

“[Social media] gives tremendous legitimacy to the (IS) movement,” she said. “So, the fact that there is such an outgrowth within the United States shows that this a powerful narrative and it is a salient message.”

The “message” has resonated with a small but active group of IS social media supporters across the U.S. According to a report released by the Center last year called “ISIS In America” — a title that uses a different acronym to identify IS, which is also known as ISIL and Daesh — more than 56 people took things a step farther and were arrested for actively assisting the terror organization in some way.

Why this small cadre of Americans is attracted to IS is far from clear. All of the experts VOA spoke with agreed there is no common profile. Of the 56 arrests last year, 86 percent of them were male; the overwhelming majority were U.S. citizens or permanent residents who ranged in age from 15 to 47.

“Statistically, the vast majority are homegrown,” Said Lorenzo Vidino, who co- authored the report. “All kinds of backgrounds, maybe second generation immigrants.”

Failing at life

If there is no common profile, there are some common traits, analysts say.

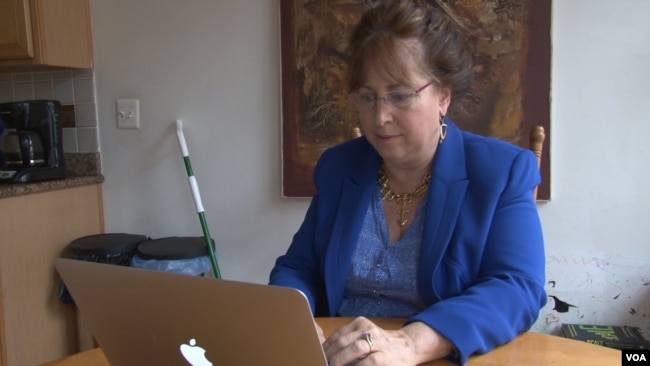

“The person that is vulnerable is the person that is off their track — that is failing in their life somehow,” says Anne Speckhard, a research psychologist and Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism in Washington, who has interviewed hundreds of IS recruits worldwide.

“It is not just their own vulnerabilities; it is that they are exposed to a terrorist network and to its ideology.”

At this early stage of the investigation, authorities are still trying to gauge the extent of Marten’s exposure to IS’s network and ideology. However, there is ample evidence that he was a person “off his track.”

In interviews, his first wife said she left him because he became violent, describing him as possibly suffering from bipolar disorder. A co-worker said he often made disparaging remarks towards women and other groups. The shooter’s father said his son was deeply angered after seeing two men kissing in front of his child — suggesting a motive for the Orlando attack.

Religion, not the primary factor

Speckhard says while there often is a religious component to extremism, it is rarely the dominant factor. She says joining an Islamist extremist group or even participating in social media banter often bring meaning and purpose to a person’s life.

Supporters of IS don’t always begin as Muslims. Of the current 3.3 million Muslims in America, about 24 percent are converts, who — over-represented among those arrested for links to IS — comprise about 40 percent of the total population.

“They stumble across Islamic extremism and then they convert,” Speckhard said. “They do it because it is meeting a need. Not because they are necessarily looking for a religion.”

Speckhard tells the story of a young Christian Sunday school teacher living an isolated life in the northwestern U.S. After IS murdered American reporter James Foley, she tweeted, “why would a terrorist behead a journalist?”

IS answered: “Because this is a revolution. Blood is shed in a revolution and we are changing the world.”

The IS recruiter then posed the question, “Did you know Islam is the completion of Christianity?” The Sunday school teacher’s conversation and radicalization began.

“She was lonely,” says Speckhard. “So all these people are swarming in on her, paying attention to her, sending her tweets, sending her messages, offering to Skype with her. And eventually she converted because she wanted to belong to something. She wanted something in her life.”

At last, after the recruiter suggested she and her younger brother come join IS in Syria, her grandmother, with whom she was living, intervened.

Family dysfunction

While that woman had a relative who ultimately proved helpful, another common trait of people who succumb to radicalization is a dysfunctional family.

Mohamed Khweis, the U.S.-born son of Palestinian immigrants was captured by Kurdish forces in Iraq after allegedly joining IS.

Khweis told his parents he was leaving their northern Virginia home to go on vacation in Europe. In an interview on Kurdish television, he said he flew to London, then Amsterdam, and on to Istanbul where he randomly met a girl whose brother was an IS fighter. She offered to take him to visit the militants.

Last week, Khweis was extradited to the U.S. to stand trial. He is charged with material support for IS, which could put him behind bars for 20 years. According to an FBI affidavit unsealed at a hearing, he admitted his intention all along was to join IS.

Speckhard says his flight itinerary was one typically used by recruits to avoid detection — a young Arabic male flying from the U.S. direct to Istanbul would probably raise red flags. She suspects he was trying to escape family troubles; IS offered a way out, and the young woman was sent to meet and possibly marry him. It all fits the pattern of what she says is a vulnerable person in need.

“I have some information that his dad was quite a drinker. So imagine being a Muslim raised with a dad that doesn’t … drink at all — and then drinks too much. That’s upsetting. So he announced to his parents ‘I’m leaving. I’m going on a vacation,’ ” said Speckhard, explaining that alcohol-abusing father figures are a factor in numerous cases of radicalization.

These cases, and the data researchers are collecting, paint a portrait of Islamist extremism in America that challenges one of the dominant talking points about terror today: that Islam is at the heart of the problem. And it begs the question, by defining violent Islamism solely in religious terms: Is the U.S. deploying resources to counter that assumption in the most efficient and effective way?

In the second part of this series, VOA explores the effect of anti-Muslim rhetoric on the Islamic community in the United States and efforts to counter terrorism.