Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Militant groups such as the Islamic State (IS) and its…

Spontaneous Deradicalization and the Path to Repatriate Some ISIS Members

Anne Speckhard and Molly Ellenberg

As published in Homeland Security Today:

“Coming to ISIS was the best deradicalization I could have.”

- Bouchra Abouallal, age 26, Belgian ISIS wife

The ISIS “Caliphate” at its apex managed to attract approximately 40,000 foreign terrorist ISIS fighters and their family members (FTFs) from over 110 countries to travel to Syria. At present, tens of thousands are still alive, thousands of them imprisoned in northeast Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) territory, held by a nonstate actor, with considerable debate among their home countries about what to do with them. Turkish-backed forces and Turkish airstrikes have repeatedly incurred into and threatened SDF authority in northeast Syria and Bashar al-Assad shows little sign of negotiating a favorable agreement with the SDF. With the COVID-19 pandemic threatening everyone in the region, and increasing cases occurring in northeast Syria of late, the political and security situation for these ISIS prisoners and their children takes on even greater urgency.

Many nations from which these ISIS men and women originated fear repatriating them, seeing their return home as highly problematic given the difficulties of procuring evidence from a conflict zone with which to prosecute them, coupled with the lack of strong counter terrorism laws in some countries. Among politicians, fears abound that their judicial systems may fail to imprison the returnees for any substantial length of time. Politicians and country authorities fear that those ISIS prisoners who may be repatriated will act as potential vectors of violence and ideological indoctrination for others, whether they are imprisoned or allowed to live freely in their communities. There are concerns that they will seed the terrorist ideology in prisons and outside of them, recruit for the group, spread their knowledge of armed conflict, and potentially also reengage in terrorist violence themselves. Indeed, some ISIS returnees have already proven that returning to, or continuing to support, the terrorist group is a real possibility.[1] In Belgium and France, ISIS returnees who were not successfully detected by law enforcement mounted horrific attacks killing hundreds.[2] For politicians, the risks of having other returnees attack on home soil are calculated as too high for their own political survival and thus impossible to take. Indeed, a Norwegian political coalition recently fell apart over the return of an ISIS woman and child[3] and there was a similar political threat in Finland.[4]

So, the question remains: What to do with these foreign ISIS prisoners and more notably their family members, particularly their young children. Is there any possibility that they can be repatriated, rehabilitated and reintegrated successfully into society, and if so how?

To answer this question, it is necessary to know the facts about ISIS returnees. More than 7,000 FTFs who traveled to Syria are believed to have returned home, many before joining or taking serious actions within the ISIS Caliphate.[5] Some of these are imprisoned, others have not been prosecuted. Many countries who have imprisoned returnees have good rehabilitation programs in place, although most are voluntary in nature. With time following return from ISIS still not long enough to have a good view on this issue, the jury is still out about returnees and prisoners released after serving under terrorism charges, with Belgium[6] reporting a low recidivism rate and France showing more concern with a 60 percent recidivism rate for French jihadists in general.

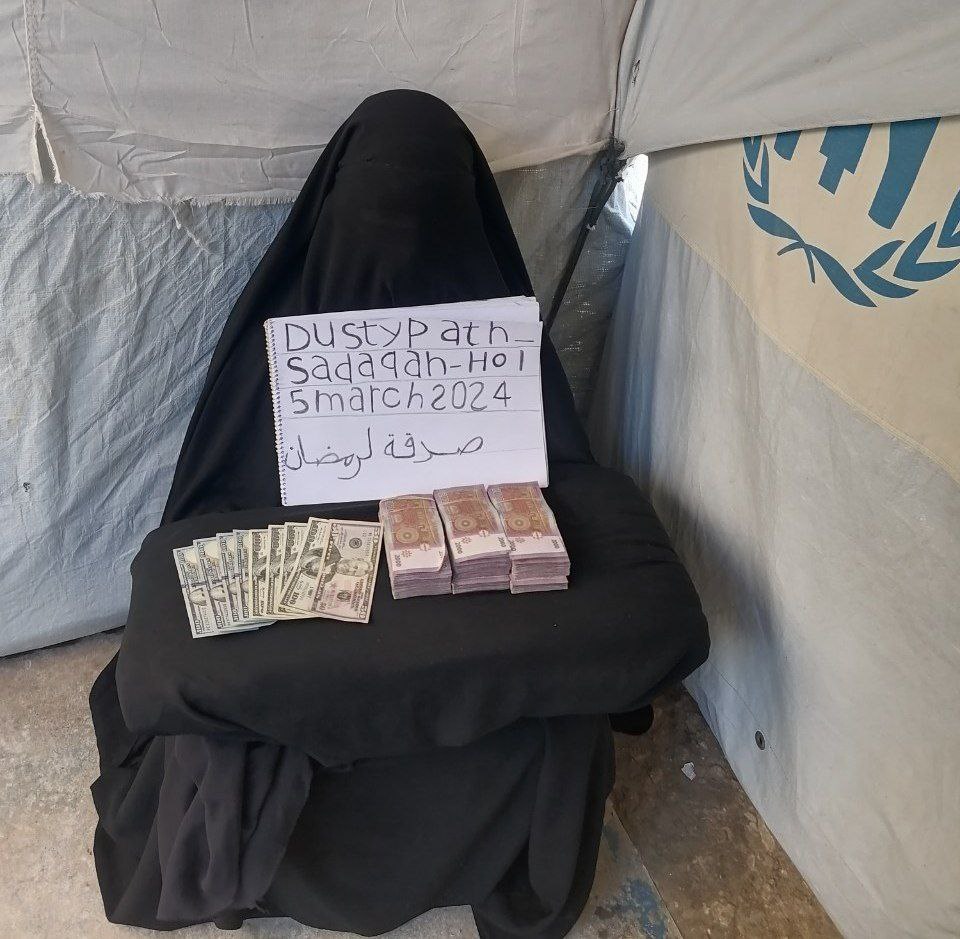

Adding to this issue is the question of how ISIS detainees held in SDF territory are currently oriented to ISIS. There is clear evidence in the women’s camps, particularly Camp al Hol, but also in Camp Ein Issa when it was operating, and less so in Camp Roj, that there are some still highly committed ISIS enforcers among the female detainees who require others to tow the ISIS line and continue to dress conservatively and who severely punish those who refuse to comply.[7] They also encourage fence-sitters to stay with the group and they try to recruit among the children. Women of this ilk also fundraise among ISIS supporters over the Internet using Instagram, Telegram and PayPal to amass funds and sometimes even arranging marriages with ISIS supporters in Europe, in order to arrange what amounts to weekly escapes of ISIS women from Camp al Hol.[8] While some escapees appear at their consulates in Turkey and request to be repatriated, others simply disappear. Men still devoted to ISIS are also active in the prisons, some highly charismatic and ideologically knowledgeable, who try to encourage the other imprisoned ISIS cadres to keep the faith or who threaten those who now denounce the group.[9]

Our research, however, has documented that there is also a considerable group among SDF-held male detainees and ISIS wives held in the camps who were immediately disillusioned of ISIS upon entering the group or who grew so over time.[10] This article examines our sample of in-depth interviewed ISIS men and women to get at the question of terrorist deradicalization and to examine an important phenomenon to which the first author refers as spontaneous deradicalization – that is, the process of denouncing the group and its ideology that takes place without any formal prison or out-of-prison program in place. It appears that the spontaneous deradicalization process occurs most frequently after disengagement with the group in returnees and imprisoned ISIS cadres, especially during long periods of time to reflect in prison, as a result of discussions with other inmates, as well as in response to negative experiences in the group before being imprisoned, including witnessing ISIS’s un-Islamic and corrupt practices, extreme brutality, hypocrisy in many situations and its territorial defeat. These all appear to contribute to a natural process of spontaneously deradicalizing, a process about which it is very important to learn and understand, particularly when evaluating the potential risks of repatriating former ISIS members from SDF territory.

This same phenomenon of becoming disillusioned by the group has also been noticed by others studying ISIS defectors and returnees who began to deradicalize outside of prison settings.[11] While most who argue that deradicalization is possible assume that a prison-based or other sort of formal rehabilitation program is necessary to accomplish it, we argue that such stringent programming may not be necessary for some, particularly those who were never strongly ideologically committed – despite ISIS’s insistence on ideological indoctrination in the form of mandatory shariah training for all ISIS men – and it may also not be necessary for those who joined ISIS to meet emotional, psycho-social and material needs that the group was incapable of meeting over any significant length of time. That is not to say that rehabilitation and reintegration should not be a goal with every ISIS returnee, or that these individuals would not benefit from various types of counseling or treatment, but that the process of spontaneously deradicalizing may already be well underway in many ISIS prisoners before they are even accepted to return home or put in any formal program. This is the issue that this article seeks to address and upon which we seek to shed further understanding.

Disengagement or Deradicalization

Over the last decade, there has been considerable discussion and debate over the dual topics of disengagement and deradicalization of terrorist cadres, with some arguing that the best hope for terrorists is to disengage them from their violent behavioral pursuits, most often achieved through removing them from the terrorist group through arrest, prosecution and imprisonment.[12] This argument falls flat, however, when one considers that there are many prisons where ISIS members are still strongly devoted to the group and where prisoners are further indoctrinated even after having returned home from ISIS.

For example, the first author interviewed Abu Albani, a 25-year-old Kosovar, both while he was imprisoned in Kosovo and two years later, after being released. Having grown disillusioned with ISIS’s treatment of women and arguing with its leaders, Abu Albani returned to Kosovo to face arrest, conviction and imprisonment. In prison, he initially feared retribution from other ISIS inmates but later joined an informal prisoner-run study group in which he and others had access to the teaching of al-Qaeda ideologue Abu Muhammad al Maqdisi. This exposure in prison realigned Abu Albani with ISIS and their militant jihadi ideals so much so that when re-interviewed by the first author after release he said he wanted nothing more than for every Muslim to rise up and follow the advice of ISIS’s then slain spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adani, who urged Muslims to kill nonbelievers, even if it meant using a rock to smash in their skulls. Abu Albani is thus a perfect example of why ideology is important to address in many prisoners and that the failure to do so may result in releasing dangerous ISIS or other militant jihadi adherents back into society.[13]

Given examples such as that of Abu Albani, it is unsurprising that many scholars and practitioners argue that disengagement from a terrorist group and behaviorally renouncing violence is not enough: that the underpinning ideological beliefs, values and narratives must also be challenged and addressed to achieve an enduring and trustworthy renunciation of violence.[14] While expunging terrorist beliefs is a much harder task than simply removing an individual from the environment and membership in the group with which they committed violence, some believe it’s achievable and more likely to reduce terrorist recidivism. Nevertheless, others argue that the fusion that occurs when an individual bonds his or her identity to a terrorist group is very hard, if not impossible, to break.[15]

Certainly, any good cognitive behavioral therapist would point out that if it is possible for a recruiter to talk a person into an ideological commitment to terrorism, it is also possible to talk him back out of it, particularly if that group is not meeting the needs he hoped they would when he joined. In that vein, it should be pointed out that individuals join terrorism for many reasons, the least of which may be ideological indoctrination. From the authors’ analysis of the ICSVE sample of in-depth interviews of 239 ISIS prisoners, defectors and returnees who were queried about their recruitment histories and experiences in ISIS, as well as many other topics, we found that often the strongest reasons among FTFs for joining ISIS was that it met their needs for belonging, significance, purpose, dignity and desires for adventure, romance and sex, and beliefs about the afterlife, as well as a deep desire to live according to Islamic ideals.[16]

Many were also ideologically driven, having adopted the concepts pushed by al-Qaeda and ISIS and believing fighting jihad and taking hijrah, that is, moving to lands ruled under shariah law, and building an Islamic Caliphate were obligations incumbent upon all Muslims. Others were less ideologically indoctrinated during the recruitment and joining phase, but ISIS nonetheless believed that ideological indoctrination was so crucial to successful operation of the group that they required all men and some women to take a shariah training course upon joining them. As a result, many became much more radicalized and ideologically committed once inside ISIS.[17] Indeed, many interviewees reference their shariah training as the peak point of their ideological commitment to ISIS, a group that teaches they are the only true believers and that all others – even Muslims – can and should be killed for refusing to join, and that also glorifies militant jihad and suicide terrorism as a type of Islamic “martyrdom.”

For these reasons, we argue that both disengagement and deradicalization are important components of terrorist rehabilitation. However, arguments also remain in regard to deradicalization in terms of questions of freedom of religion, policing thoughts and the right to privacy. While many scholars of rehabilitation argue for prioritizing disengagement for the group, our view is that given how important ISIS felt ideological indoctrination was, requiring it for all male members, deradicalization should also be a goal of good treatment for those ideologically aligned to ISIS. While addressing virulent ideological beliefs in a prison, or other type of rehabilitation program, for ISIS returnees could be construed as violating freedom of religion, it should be noted that cognitive behavioral psychologists frequently address patterns of thought and ideological commitments that are maladaptive for the individual or society and that propel an individual to commit crimes of violence toward himself and others. That is simply good therapy. Thus, helping a prisoner to think through whether or not ISIS’s ideology is supported by Islamic scriptures and serves the person adhering to them should also be considered good cognitive behavioral treatment that does not necessarily have to violate religious beliefs nor punish a person for his or her thoughts. It simply begins a process of questioning and coming to a healthy adjustment to the society in which one lives.

In this article, however, we examine the instances wherein this process begins on its own – without a formal process in place.

Research Method

All of the participants in this study were interviewed by the first author, a research psychologist. Following an informed consent procedure, the research interviews began with a brief history of the individual’s early childhood and life before ISIS, then moving toward how the individual learned about the conflicts in Syria, and about ISIS, and became interested in travelling and/or join. Questions explored the various motivations and vulnerabilities for joining and obtained a detailed recruitment history: How the individual interacted with ISIS prior to traveling and joining, whether recruitment took place in person or over the Internet, or both, and how travel was arranged and occurred and what happened subsequently in Syria and Iraq. It is the recruitment section of the interviews on which this latter half of this article will focus. Additional interview questions covered the individuals’ roles and experiences in ISIS, sources of disillusionment, and changes over time in orientation to the group and its ideology, often from highly endorsing it to wanting to leave. A full report on the research, as well as the ethical considerations of human subjects research with vulnerable populations such as prisoners, can be assessed in an article by Speckhard and Ellenberg (2020).[18]

Results

It should be noted that all of the interviewees’ statements were taken at face value, which could mean that prisoners, in particular, lied about their current levels of radicalization. However, given the in-depth nature of the interviews and the fact that the interviewer warned the subject not to admit to or discuss crimes they hadn’t already admitted to, it appeared possible to gauge a level of honesty as the detainees had nothing to gain from lying to the interviewer. Most spoke for over an hour about their experiences, many noting things they liked about ISIS and some openly admitting they were still aligned with ISIS. The experiences of those who had begun spontaneously deradicalizing were usually so brutal and traumatic that it was not hard to believe that they had really gotten angry, hurt and remorseful about ever having trusted and joined the group and were presently as a result very disillusioned with it.

For instance, Abu Isaac, a 28-year-old Kosovar, was frustrated by a difficult work and family situation at home in Kosovo, when he got recruited into traveling to ISIS by Macedonians who told him that he could be hired by ISIS to work in Syria with other Albanians. Abu Isaac was at first enamored of the ISIS ideology, yet upon his entry into Syria events began to chip away at his faith in ISIS. “I started getting doubts,” he recalls. “They put this 50-year-old Albanian man in prison. What they preach is different than how they act.” Abu Isaac recalls also being upset seeing Russian bombs killing children and feeling disturbed by ISIS’s brutal punishments and executions. “Then, I saw killings and stonings, horrible things that were very horrible to watch.” Seeing an ISIS execution in Manbij, Abu Isaac recalls, “I saw 10 people lined up. They killed them in the center of the city. This was the most terrifying thing I saw. I asked my friend who was with me, ‘What is Islamic about this? I don’t understand.’ It was four [ISIS guys.] They used a machete, a few knives cutting their heads and a gun on the remaining. Honestly, for two, three days I just couldn’t sleep. Another example, this woman was buried to her throat. She was circled around by 20 guys. They had stones in their hands, and they started stoning her. There was no day passing by that you wouldn’t hear these things happening in the center. It was happening on a daily basis.”

Abu Isaac was later imprisoned by ISIS when overheard complaining to his father while communicating via an ISIS Internet café. He recalls his punishments, “I was tortured so badly. Nothing even in Guantanamo would not be that bad.” Abu Isaac describes, “They hooked me up in an electric bed, tie you down and high voltage power… You get the idea. They put me in a tiny 2×2 room and filled it up with water up to your throat and you watch a tiny opening above and they put me there for eight days. Another torture, [they put a] towel in my mouth and run water heavily every 15 seconds. When I came out of prison, when my wife saw my body, she said, ‘Where have you been?’ I had bruises all over my body. How can this happen in the Islamic State?”

In the end, Abu Isaac was captured by the SDF, in whose custody he was interviewed by the first author. While he admitted to having doubts all along during his time in Syria, his feelings eventually grew to a full hatred of ISIS. Whatever first acceptance he felt for their promises to deliver an Islamic Caliphate have now been completely shattered. He has deradicalized himself in that, if he is telling the truth, he now hates ISIS and appears unlikely to ever return to them. He also sees the effects of ISIS behaviors not only as they relate to himself, but upon their victims, as he advises those who might still think of joining, “For people who think about doing things like that, take into account that the people they are going to harm have families. You are going to hurt them.” Speaking of ISIS’s penchant to attack the West, he also asks. “How do you fight against the land you have to return to, attack your own country?” While Abu Isaac still has the last piece of work to do of taking responsibility for his actions in the group, that is coming to terms with that he was an active cog in the machinery of an evil group that hurt many, and that his actions in part made that possible, he is already at the point of seeing that many suffered needlessly. Looking back, he states that he was naïve in believing the ISIS’s claims of building an Islamic utopia. “A lot of people who came had no idea about religion. They were manipulated into coming and when they came here it became so difficult to come out of this shithole.” Looking back at his own desire to be employed and other vulnerabilities he states, “They took advantage of my weakness. I had psychological depression. They took advantage of it.”

Belgian Salma, aged 22, also deradicalized even before being arrested by the SDF on her third attempted escape from the group. Tired of the ISIS fascist governance and violence toward their members and those they governed, Salma and her father and husband decided to try to smuggle out of the ISIS territory. They were all arrested by ISIS on their first attempted escape, with the men being imprisoned and tortured by ISIS. Their second attempt ended worse: “They started shooting on us. They killed all the men. [My father] died in front of me. I got a bullet in my back and a bullet [in] other places.” All of this occurred while Salma held her newborn baby in her arms. Salma is highly unlikely to ever rejoin ISIS given that they executed her own father in front of her.

In analyzing the quantitative data on these interviews it’s apparent that aggregated, the spontaneously deradicalized interviewees were more likely than their not spontaneously deradicalized counterparts to report emotional abuse, sexual abuse, parental separation or divorce, unmarried parents, family conflict, leaving home early, and personal divorce as vulnerabilities to radicalization and recruitment into ISIS. In contrast, those who had not spontaneously radicalized were more likely to report a criminal history and a father with multiple wives as vulnerabilities. When disaggregated by gender, spontaneously deradicalized men were more likely than their non-spontaneously deradicalized counterparts to report unemployment or underemployment as a vulnerability. There were no significant differences in vulnerabilities reported by spontaneously deradicalized and non-spontaneously deradicalized women, likely due to the smaller sample size.

The motivations for travel to Syria and joining ISIS of the interviewees in the two groups also differed greatly. Those who had spontaneously deradicalized were more likely to report more existential and self-actualizing motivations, namely emotional escape, romance, desire to consolidate a traditional feminine identity, and a sense of belonging. Disaggregated by gender, spontaneously deradicalized men were more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized men to have been motivated to travel and join ISIS by basic needs, employment, emotional escape, and a sense of belonging. The basic needs and employment motivations illustrate that these individuals were more likely to have joined the group out of desperation, rather than ideological alignment. There were no significant differences in motivation between spontaneously deradicalized and non-spontaneously deradicalized women, likely due to the small sample size.

In contrast, those who had not spontaneously deradicalized reported motivations for joining that adhered to ISIS’s ideology and reality, namely an anger-based purpose, jihad ideology, hijrah ideology, anti-Western ideology, and a desire to fight for Sunni rights. In this regard they can be said to have had more ideological reasons for joining than those who spontaneously deradicalized. Likewise, those who had not spontaneously deradicalized were more likely than those who had to report having previously been arrested for ideological offenses as a motivation for joining, again underlining that they appear to have been more ideologically indoctrinated into militant jihadist thinking even before joining ISIS and were thus less likely to spontaneously walk away from it.

Indonesian Abu Miriam was one who was motivated to join ISIS by promises of employment and acceptance. The 29-year-old, who was interviewed in SDF territory, was recruited into ISIS through a friend who had joined and told him he should come to learn his religion, get work and escape his family problems. Abu Miriam recalls, “He promised me a lot of things. We will have a good life here, good job here, and the people here will treat you in a good way. But it was all lies. After I came, I never even met him.” While Abu Miriam had moved his family to Syria hopeful, as a result of believing ISIS’s recruitment lies, he and his wife were quickly disillusioned. Abu Miriam’s wife was angry about being left in the dirty ISIS guest house while he was taken to shariah and military training and she complained that she had been mocked for not knowing about Islam, despite their coming to join the Islamic State to deepen their knowledge. Abu Miriam tried to find a way out but was thwarted by terror over his realization that ISIS killed those they caught trying to escape. “I realize they are like a mafia,” he said. “They are forcing people to do what they want, to believe what they want. It’s not like what my friend said, that you can live freely here. If someone wants to leave their job, they put him in prison. Baghdadi is a big liar. He lied to everyone. He provoked people to come to this area and treated us like we are prisoner[s] of them.”

Abu Miriam recalls being in denial at first about the ISIS executions he was hearing about until he saw their corpses hanging in Raqqa’s central square. “I never believed this. A lot of people told me ISIS was doing this, but I didn’t believe it.” Referring to how the executed had signs accusing them of being unbelievers, he states, “They are using these religious things to make people think what they are doing is right to cover their crime. It was like the worst dictator in history and the worst thing [is that] they use religion to cover it. It was not an Islamic State, [as they were] claiming to be. They were killing Muslims and saying he was a disbeliever, accusing them. I met people who said here was a good guy and they killed him. They were using fatwas, to cover their crimes. It’s not real Islam.”

Abu Mansour, a 34-year-old Saudi Arabian also interviewed in SDF territory, was motivated in part by ideology, but also by a desire to escape from a negative emotional situation at home. He states that he joined ISIS because, “I felt it was duty to support people after the Caliphate established. I wanted to support the good community.” He also admits that by joining and traveling to Syria he was evading a painful situation: “At that time I lost my fiancé. I had problems in my life. I wanted to support Dawlah [the Islamic State], this religious thing [and] the people of Syria, but I think I [also] wanted to start a new life. I wanted to revenge for myself. Escape, yes, I think it’s the reason.”

Abu Mansour recalls that even early on, in shariah training, when they taught him to takfir entire nations, that is, reject them as un-Islamic because their leaders were not following the correct Islam according to ISIS, he disagreed. Abu Mansour recalls, “I thought about escaping a lot. They took our passports when we came.” He brings up an issue many FTFs address, the reluctance to risk going to ISIS prison or being arrested if they managed to escape to their home country where they also feared being imprisoned. It was a calculus that did not seem worth the risk. “I was afraid to go out. I will go to prison for minimum of 10 years. I was waiting for something to happen, in 2014-2015. If you get caught [trying to escape], Dawlah will put you in jail. [You will be] tortured and killed.”

While initially wanting to support the Islamic State enough to travel there to join, Abu Mansour now says, “Dawlah was wrong. It’s all wrong. They took a part of Islam, the rest no.” Tired of their hypocrisy, he points out, “In the beginning they said Jaysh al Hur (the Free Syrian Army) was kuffar [unbelievers] because they sold oil to Assad but when we [captured them, we said,] ‘Give us your gun, you are safe,’ and after two days we took them and killed them. No one does that. Islam says if you give your word, you have to follow it. Anything they didn’t want they made haram [forbidden]. Sabayah, it was bad. They didn’t treat them humanely, selling a lot of young girls and young boys. It was sad.”

Abu Mansour warns others, “Don’t follow religious men in general. Most of them are liars. The Dawlah guys are liars.”

In making their decision to join ISIS, the spontaneously deradicalized participants were also more likely than the non-spontaneously deradicalized group to report being influenced by a parent, face-to-face recruiter, passive consumption of content on YouTube, Twitter, and WhatsApp. These interviewees were also more likely to have been actively recruited online. Unsurprisingly, therefore, they were also more likely to have had any sort of online recruitment or travel facilitation but they were not more likely to report that their recruitment occurred solely online. The non-spontaneously deradicalized participants, however, were more likely to report influence by siblings and extended family members perhaps underlining that when terrorism is a family affair, the ties to the group are strong and it’s more difficult to leave the group as doing so means cutting ties with one’s family members as well. Disaggregated by gender, spontaneously deradicalized men compared to their non-spontaneously deradicalized counter parts were more likely to be influenced by their parents and less likely to be influenced by their siblings. There were no significant differences between spontaneously deradicalized and non-spontaneously deradicalized women, likely due to the small sample size.

Abu Musrata, a 23-year-old Libyan interviewed in SDF territory, recalls joining ISIS at age 17 after watching “videos of women under Bashar. When I came here with a group; we didn’t know about Nusrah, Dawlah any of them. We watched the videos in high school on the Internet, Facebook. They were screaming, ‘Where are you Arabs?’” Abu Musrata states that he came to fight Assad, “I didn’t used to think about Khalifa. My thought was to come to get rid of the regime of Assad to get rid of him like we did Qaddafi.” However, Abu Musrata eventually joined ISIS and recalls, “At the beginning it was so good, but later it was a question of Iraq, Sunni against Shia, and they used us.” He attributes falling into their ideology as, “Brainwashing, they turn around it, little by little.” Over time, he realized he was being deceived, “We discovered all that.” When it came to ISIS’s teaching about suicide terrorism, Abu Musrata also did not accept it. “For me it’s haram [forbidden in Islam]. It’s a sin. The words of Allah are much more important than Baghdadi. When he says go and kill yourself, I saw the words are not the same.” Now he admits, “I was stupid. Baghdadi cheated me.” He advises others, “Don’t be excited. Don’t be emotional. Those [ISIS recruitment] videos were lies.” He also counsels youth not to be advised about one’s religion from extremists, “[When it comes to] Baghdadi and Zarqawi, don’t take it from them. Take it directly from the Quran and sunnah.”

Abu Tahir, a 25-year-old Tunisian, joined ISIS after chatting over the Internet with a “a Tunisian friend who was here in Syria … He told me about Islamic State and good things.” While corresponding, Abu Tahir began to watch ISIS videos which influenced him. “I am a believer, praying. The most important was the videos that affected me. I was seeing that there is Dawlah. There is justice. Everyone equal.” This was happening while Abu Tahir was being pressured and feeling persecuted by the Tunisian police for having become religious. “If you go often to the mosque, they look at you in a different way. This affected me.” While Abu Tahir arrived at ISIS territory enthusiastic, he was put off in their shariah training by the ISIS practice of takfiring those not adhering to ISIS’s ideology. Speaking of the Jordanian sheik who taught them he recalls, “He was so tough by definition of kufr [unbelievers]. All people outside of them are kufr.” When Abu Tahir argued back, “They accused me of mushrik, [being] the kind of Muslim who refuses the real decision of Islam. He wanted to stab me too.”

Abu Tahir was disappointed by the infighting and wanted to leave ISIS. However, he was warned by the ISIS emni, their internal security apparatus, that he could not. He recalls, “[There were] so many opinions on takfir about it in the guesthouse. I thought it, [ISIS], was one hand, unified. All of them tried to quit ISIS early on.” He also began to compare the cruelty of the ISIS emni to what was going on Tunisia. Abu Tair dropped his positive affinity to ISIS within the first month of joining them in part because of their un-Islamic teachings and also because they forced him into military training despite his asthma and inability to breathe in dusty conditions. “I wanted to go out. When you come you discover some liars, first reaction is to go out.” He continues, “I say they cheat on us. They are cheaters, liars. We discover what is Dawlah.”

Abu Tahir also condemns ISIS’s practice of suicide bombing and terrorism in the members’ home countries as un-Islamic: “According to Islam, it’s forbidden. Mohammed said you cannot kill innocent women and children, even the men, if they are not against you. What is the result of stabbing, or blowing up a car?”

Abu Tahir wishes to be repatriated to Tunisia, especially to beg his parents’ forgiveness, particularly his mother, who fell very ill in response to his leaving. He totally rejects ISIS at this point, realizing the corrupt, brutal and unIslamic nature of the organization. He clearly explains, “So I came to this Dawlah [Islamic State] and I know it’s cheating, and I discover all that. The whole thing is that you are contributing to the interests of one man who wants to sit in one chair and lead, like all the Arab regimes. It’s all Baathist. I could see their Baathist thinking.”

Once in ISIS, those who had joined hoping for an idealistic, fulfilling, meaningful life under the Caliphate were most often quickly disappointed. Thus, the spontaneously deradicalized interviewees were more likely than their non-spontaneously deradicalized counterparts to report ISIS’s behaviors of civilian mistreatment, attacking outside of ISIS territory, mistreatment of ISIS members, mistreatment of women, and the practice of takfir as sources of disillusionment. This group was also more likely to be disillusioned by lack of pay, likely reported by those who joined in order to have their basic needs met.

Those who did not spontaneously deradicalize also reported sources of disillusionment, albeit their sources of disillusionment were with ISIS’s management and structure versus its brutality and ideological inclinations. This group was more likely to report disillusionment over ISIS’s cooperation with Assad’s regime and favoritism toward local Iraqi and Syrian ISIS members. Unsurprisingly, the spontaneously deradicalized participants were more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized participants to report no longer supporting ISIS and no longer supporting militant jihad. Perhaps because they were seeking far more from ISIS than their non-spontaneously deradicalized counterparts, the spontaneously deradicalized interviewees were also more likely to complain that ISIS had cheated, lied, or otherwise manipulated them into joining.

Disaggregated by gender, spontaneously deradicalized men were also significantly more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized men to be disillusioned by lack of pay and mistreatment of ISIS members. Spontaneously deradicalized women were more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized women to be disillusioned by ISIS’s attacks outside of their territory, particularly in their home countries. Spontaneously deradicalized women were also more likely than their non-spontaneously deradicalized counterparts to state that ISIS had cheated or lied to them. Without the inclusion of women in the sample, spontaneously deradicalized men were not significantly more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized men to state that ISIS had cheated or lied to them.

Kimberly Pullman, a 46-year-old Canadian, was, like many of the female interviewees, disillusioned by ISIS’s especially brutal treatment of women. Kimberly had suffered a history of sexual abuse before joining ISIS and she had joined the group in the hopes of restoring her honor, helping children, and finding love in a group that claimed to view women as precious. After she arrived in Syria and began to question things, her ISIS husband, whom she met online, labeled her an infidel and forced her to live in a madafa, the squalid ISIS guesthouses where unmarried women were held captive until they married ISIS members.

Kimberly recalls the trauma she experienced when she tried to escape: “The first time I tried [to escape] was about six months after I was in the madafa. The second time that I would try [to escape] was when I remarried. Then, they threw me in prison [for] about a month. They accused me of being a spy. You could hear the screams down the hallway. I would see different men all in different stress positions and they were all blindfolded. There was blood all over the floor, so I was trying not to step in it. They made me watch and they told me that if I didn’t start giving information that this was going to happen to me, too. There were nine women in there. Three of them were marked for death. One had been tortured pretty badly. I asked them, ‘How on earth is this anything Islamic? I have a husband somewhere down the road and there’s eight men alone with me in a room and this is supposed to be the best of the Muslims in the world? You must be joking, right?’ They didn’t like that very much. That was the same night that they slammed my head into the door. I remembered thinking that, ‘If I actually live through this, this is going to be a bit of a miracle.’”

Abu Fatima, a 30-year-old German, converted to Islam before joining ISIS. He later learned that ISIS was not practicing the “true Islam,” as he was told. While Abu Fatima initially enjoyed living under ISIS, he says they later became un-Islamic: “They did very bad deeds, they killed people without any evidence, to steal houses and use their stuff is not Islamic, to torture people is not Islamic, to leave your people without money and salaries is not Islamic. If all of us didn’t have anything to eat, it’s OK, but when you see emirs have everything, money and food, and we have nothing, it’s not Islam. It’s not fairness.”

Abdel Ahmed, a 19-year-old from Pakistan, started out his jihadist life as a youth at a training camp in Pakistan to support an independent Kashmir and to also prepare to defend Pakistan from Indian military incursions if need be. Abdel was only 14 when he started following Syrian events “on social media, Facebook and Twitter, searching, and making contacts.” Abdel met an online recruiter and came to Syria.

Inside ISIS, Abdel became disillusioned. He recalls the case of a Kurdish American, whose name he does not recall: “[The American] came from Turkey to see what’s happening. He wanted to teach the people English and they sent him to Iraq and to Mosul. [After,] he was totally silent [traumatized]. Many bad things happened to him. He refused to fight. They put him in prison. Cut his salary. This poor guy he had to sell his laptop to survive. They put him in prison six times in Syria. He became a beggar. He was selling cookies in the mosque in Raqqa. He tried many times to get out, but he couldn’t. He’d end in prison over and over again. You might cry to see this guy.”

Abdel recalls his distress about ISIS forcing people to be fighters for them, “The people who didn’t want to go to fight, they put in prison. These things were happening in front of my eyes.”

Based on witnessing things like this Abdel became deeply disillusioned with ISIS. Now he says, “I would advise these people who are still believing in Islamic State, it was a fake state. They pretend that there was Islam here, but it was just drama performed by Iraqi people. It was for them, nothing for the Muslims. There was nothing beneficial for the Muslims and for those of us, like me, who came out, they will say the same story. ‘Don’t join any group. Don’t do this. This stupid thing, it’s not a solution.’ I wanted myself to help someone. They didn’t help anyone. They didn’t help the people. Who more can deserve than injured people and who fought with you and you just throw it away like a piece of paper? They imprisoned and killed their own people. They were oppressors. It was a very twisted view of Islam. I didn’t hear about this when I was in Pakistan, I didn’t hear about all the killing people and if you can suicide. Can you kill people who want to leave? What I saw! What it was! Anybody can say it was not an Islamic thing that happened to give a gun to a 3-year-old kid to kill someone, killing and imprisoning those who want to leave. Anyone can say this is not Islamic!”

In addition to ISIS’s brutality, many of the spontaneously deradicalized interviewees were disillusioned by ISIS’s practices that were contrary to the values of the utopic Islamic Caliphate they hoped to have joined. For instance, 24-year-old American-born Hoda Muthana expected to find a group in which every Muslim was treated equally. Rather, she says, “Their way of ruling is not Islamic at all; for example, they would treat weak people with aggression and give wealthy people a pass. That was not Islamic at all.”

Interestingly, examining the participants’ lived experiences in ISIS reveals that it is indeed shattered expectations and disappointment that precipitate spontaneous deradicalization; it is not necessarily physical events such as being traumatized by bombs or battle, but rather the individuals’ reactions to and perceptions of those events. Indeed, the spontaneously deradicalized group was not more likely than the non-spontaneously deradicalized group to report experiencing any traumatic events, including being tortured or imprisoned by ISIS, being raped, being forced to marry or fight, witnessing executions, and participating in atrocities as a member of ISIS, among others. The only significant difference in traumatic experiences was that the non-spontaneously deradicalized group was more likely to report experiencing the death in Syria or Iraq of a family member during their time in ISIS, as a result of direct ISIS violence, bombings, or starvation.

Spontaneously deradicalized participants were more likely to feel that ISIS had cheated or lied to them. This may suggest a denial of personal responsibility or perhaps a dual reality that they were both lied to and also bear responsibility as well, for having taken part in the group. This issue was rarely addressed in their remarks about having been lied to, remarks in which they saw themselves as victims rather than grappled with their own actions that had harmed others or their support to the group that had deeply victimized others. In that vein, spontaneously deradicalized men were more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized men to say that they should be prosecuted, to express remorse for the familial consequences of their joining ISIS, and to express remorse for the crimes they committed as an ISIS member. Spontaneously deradicalized women were also more likely than non-spontaneously deradicalized women to express remorse for the consequences their joining ISIS had on their families, but there were no significant differences in the women’s likelihood to say they should be prosecuted or to express remorse for crimes committed in ISIS. This may reflect that women in ISIS often functioned as wives and mothers and as a result don’t necessarily feel guilty over familial roles and participation in the group nor believe they should be prosecuted.

Abu Asma, a 21-year-old Saudi Arabian who was interviewed in SDF territory, recalls being ideologically indoctrinated during high school in Saudi Arabia about the Islamic obligation to fight jihad, particularly as events turned bad in Syria under the Assad regime. He recalls watching videos where the Syrian regime was claiming there is “no God, only Allah and Bashar” and feeling hurt and touched by these videos. He recalls that he wasn’t committed to ISIS or al Nusrah, saying, “I was coming for jihad. I saw the people [asking], ‘Where are you Muslims? Where are you Arabs?’” Abu Asma recalls expecting to be “martyred,” saying, “I was thinking I will not last long in Syria.” Serving in al Shishani’s brigade, he recalls, “I wore a suicide vest as did Shishani.” Abu Asma gradually became disillusioned with ISIS, saying, “In 2016 I discovered I was wrong in Daesh.” He was particularly disillusioned that ISIS were not only fighting the Syrian regime, but al Nusra and the Kurds as well. He recalls, “I was refusing to fight against Nusra.”

Abu Asma also felt sickened by the enslavement of Yazidi women and girls: “When they took the sabaya [female slaves] from Iraq and Homs villages it was so sad for me, what I saw from those women. When they came to Raqqa, the women were saying, ‘We are Muslims. We pray like you.’ We [foreign fighters] came for the Muslims and this is a bad image of Islam. It’s sad in 2016.”

Abu Asma is also angered that ISIS killed Saudis and Tunisians who tried to leave the group and that Baghdadi urged terror attacks at home as well. He asks, “What the hell are you going to win? This is not Islam!” While Abu Asma was originally indoctrinated to believe in the jihadist concept of militant jihad, he does not agree with ISIS’s belief in attacking Shia or in creating a worldwide jihad. “[Back home,] my cousin blew himself up against a Shia mosque. This is a house of God. He killed himself for nothing.”

Abu Asma recalls how he came into ISIS expecting Islamic ideals: “When we came here, we came to read Islam, help Islam [but] we find a big trap and we enter it. We were under two fires: the one who leaves Daesh he will be killed. We were in a comfort situation in our countries and now we wish [to return home]. If we go to Saudi, it’s another prison, 15-20 years. We didn’t know where to go.”

Abu Asma managed to contact Saudi intelligence, but in exchange for helping to extract him, the Saudi security officials asked him to help bring back some orphaned boys whose father had killed himself for ISIS in a suicide mission. Abu Asma was arrested by the SDF before he could accomplish it.

Abu Asma now says he knows he was one of many “stupid kids that dreamed stupid dreams.” He clearly states remorse: “I express my feeling to my country to Saudi and I recognize my mistake and I want to come back to my country.”

Now looking back at the criminal nature of ISIS as opposed to his own country’s willingness to rehabilitate those who joined, Abu Asma says, “We feel so bad. We were not at the level with our countries. We did all that and they are welcoming us. [When] they said, ‘Your kids are Saudi and we are obliged to help you,’ I was ashamed.” He compares his treatment in ISIS to how Saudi Arabia would treat him: “Even if I sit in prison in Saudi, how they treat people, visiting the wives and the parents and communicating, the services. You can study. You can get a diploma. They can give you a job, money go and restart your life. They have a program. They rehabilitate you to bring you back to your society. They call you a guest and not a prisoner.”

All of these revised thoughts about his own country have filled Abu Asma’s thoughts as he waits to learn his fate as an SDF prisoner. “I discover it here. I was thinking in another manner, that they are an enemy of Islam. I was naïve. I was an idiot.” He also shows true remorse, “I know, and I regret it,” even thinking of how he could make reparations. This thought about how to make amends to victims is not always a common trait in those who are deradicalizing. “I want to do anything to correct or recover my mistakes.” However, he does point out that the Coalition also killed civilians. Unlike many others, however, Abu Asma admits his guilt. “I feel those who died by my hand, to tell them how wrong I was. I hope they will forgive me one day. I am so sorry.”

He also advises others not to repeat his mistake in joining ISIS. “I tell all the others don’t do what I did. Don’t join people in a trap, in a hole. Your victim will be kids, elders and women, poor people.”

The process of deradicalization is multilayered and is not always the reverse of the radicalization process. In the case of ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners, the process, just like radicalization, is a highly individualistic one and can occur suddenly at any moment in time, or more often, occurs over a considerable length of time such as when events contradicted the ISIS ideology and underlined the brutality, corrupt and unIslamic nature of the group. In most cases, ISIS members reached their peak of radicalization during their shariah training, a time during which they were sheltered from the realities of ISIS rule and were being heavily indoctrinated by learned Islamic scholars. For some, spontaneous deradicalization began immediately after shariah training when they learned they couldn’t dodge fighting duties, had little say in their futures, when they witnessed ISIS’s criminality, or other surprises that contradicted what they had been told about ISIS and the Caliphate. Others took a longer time to deradicalize, but once their doubts grew strong, many found it nearly impossible to escape the group and had to stay silent and endure. In some cases, it was not until ISIS began to falter, losing ground as its enemies heavily bombarded their territory or the individuals themselves, or family members and close friends, were imprisoned, tortured, punished, or executed by ISIS that they began to seriously question their involvement and commitment to the group. Still others did not begin to deradicalize until they were in ISIS’s last stronghold and seeing Iraqi ISIS leaders with food while many starved. Others didn’t begin to deradicalize until they had surrendered or were captured and put in prison, or in the case of female ISIS members, detention camps. Prison affords long periods with one’s thoughts, not to mention other disgruntled prisoners, who can begin to disassemble the ISIS indoctrination, provide extra examples of ISIS’s brutality and un-Islamic nature, and the fact that joining ISIS did not work out well for the individual in question, as well as all the others imprisoned with him or her. Likewise, for those facing death sentences, as was often the case with Iraqi imprisoned interviewees, contemplating one’s death makes the individual acutely aware of the possibility of eternal judgement and punishment for having been involved with ISIS.

Abu Hashim, a 28-year-old Iraqi, was not deeply radicalized but agreed to support ISIS in Iraq. He claims he joined ISIS for the money and became a driver delivering explosives from Usifiya to Baghdad. Once in, he was coerced to continue by threats from ISIS to turn him into the Iraqi forces if he refused. He used the money to buy clothes, eat and pay for a phone card to keep in touch with a girl he hoped to marry. Abu Hashim recalls his horror and fear when he heard about the car bombs he had helped equip exploding in Baghdad. He recalls having post-traumatic nightmares, shock and flashbacks about those who were killed. Now after spending time in prison, Abu Hashim regrets that he served ISIS and is anxious about eternal judgment for having done so, stating, “I’m scared about what I will tell Allah. He won’t forgive me.” He also states that ISIS are not good Muslims: “They are killers. They like to spread blood everywhere.”

Kenyan Aisha, aged 27, was stopped in India on her way to join ISIS and become a suicide bomber with a man she met online. Now, having spent time in prison to reflect, she has come to the conclusion that she would not have gone to Paradise had she gone through with her ‘martyrdom mission.’ She advises other young women to go to Jannah in a different way: “To respect your parents […] show them you love them.” She warns them sternly against joining ISIS and fighting for them, saying, “If you do these things, you’ll go to hell.”

Locals who deradicalized often did so during their time inside of ISIS and defected from the group as a result. These defectors were ideologically aligned in the beginning, often hoping ISIS would win them political rights as Sunnis and became even more so after taking ISIS’s shariah training, which they believed at face value to represent Islam, but became disillusioned when they saw ISIS’s true nature. These cases are a sampling of local Iraqis and Syrians who fall into this category. In the case of the Syrians, they defected and escaped into Turkey and were not arrested. In the case of Iraqis, the Iraqi security forces later caught up to them and they were prosecuted and imprisoned even though they had defected from ISIS.

Syrian Abu Musab recalls joining ISIS with his friends in Deir ez-Zor after listening to the ISIS preacher give lessons each night in his local mosque. “He taught us about everything – prayer and about how the Islamic State is good, about doctrine, Islamic belief, and the unity of God. He taught us everything about religion. He was the person who knew about shariah in the area of Deir ez-Zor. We young people liked him. We went to the mosque daily to attend his lectures. Then he asked us about declaring our loyalty to the state – giving our ‘bayat’ [pledge of loyalty].” This ISIS preacher talked Abu Musab and his friends into coming to the Cubs of the Caliphate training camp. “The shariah teachers [extolling martyrdom] tried to convince us that when you die you won’t feel it.”

Later, Abu Musab was sent to slaughter their neighboring Sunni members of the al-Sheitaat tribe and paid well for his work. “At first, they gave us $100 U.S., but now I got $1,000. It’s really a lot of money. They were really giving us a lot of things every time we stormed somewhere.” But he learned that the slaughter occurred under false pretenses. “We thought they had Free Syrian Army cadres among them, but later we learned that they were just natives from the area trying to defend themselves. But there were oil fields…” Abu Musab’s mother and uncle told him to quit over this issue but Abu Musab feared ISIS would kill him if he defected. “People hated us because we had killed the entire al-Sheitaat tribe. We had become pariahs. … My mother was sick because of me. My uncle kicked me out of his home.” Abu Musab recalls his friend who had also joined the Cubs of the Caliphate encouraging them to defect: “‘Look what they did to the al-Sheitaat and to the Kurds, the blood!’ I started fearing blood. They brought a murtad [renegade] and they slaughtered him. I had to go back. I couldn’t see it. A Chechen started yelling at us, ‘You have disappointed me! You people of Islamic State, you have to learn to slaughter and behead!’ But it made me sick how they would yell ‘Allah Akbar!’ [God is Greatest!], and I thought about what my colleague said, that we should probably leave. It was a seed in our minds. We wanted to defect.”

Abu Musab continued to be sickened by how ISIS would kill his fellow Syrians: tribal members, Kurds and members of the Free Syrian Army [FSA]. According to Abu Musab, ISIS fighters would “slaughter without even investigating, [saying], ‘We took this guy straight to punishment.’ They didn’t even take them to the shariah court. Most would scream, ‘I am innocent! The Free Army is on the right path. Allah Akbar!’ Then they would kill them.” Abu Musab finally got in contact with a Kurd who pointed out to him that ISIS was not even fighting the regime but was at that time mainly fighting the FSA. Abu Musab also became disgusted with the foreign fighters who preyed upon Syrian women and encouraged their countrymen to join them in Syria, saying, “There are beautiful women here and there is a lot of money and cowardly men.” When he found a way out to Turkey, Abu Musab defected from ISIS.

Abu Munthir, an 18-year-old Iraqi, was recruited as a teenager in his mosque by ISIS with the offer of a paying job. Abu Munthir defected from ISIS but was later arrested and was interviewed by the first author in an Iraqi prison. He reflects, “In the beginning I thought they were good Muslims. That’s why I joined them, then I understood, no.” Once inside ISIS, Abu Munthir began to see disturbing practices. He recalls, “They used to sell these Yazidi girls. We used to feel bad for these girls. They had nothing to do with anything, but they are put in a pickup truck and they spin them around, for nothing. I felt bad.” He states, “Once I saw them smoking and they prohibit others. [Then,] I saw them as hypocrites. How can they do it themselves? Of course, I saw them stealing from everyone. If you have a market, they take some of the money from your shop. They steal from everyone. They would eat the best food ever while others were very poor. They were fake.”

He also reflected, as did many locals in areas overtaken by ISIS, that they were good in the beginning but became brutal over time: “At the beginning they were really good with us, didn’t do anything against us. But then they started treating us badly, especially the [Iraqi] military and police. The families of the military and police who left Mosul, they kicked their families out and took their houses away from them … and those inside the services, they killed.”

Abu Usama, a 17-year-old Iraqi interviewed in Iraqi prison, recalls his older brother taking him to Mosul where he was working as an ISIS fighter and guard. While Abu Usama was willing to trust his brother enough to join ISIS, he had his doubts about ISIS’s Islamic nature as soon as he began to observe their behaviors. “I wasn’t convinced. I would say the Quran did not say like that, to punish when you don’t follow the rules. I argued with my brother. From the beginning I was not convinced. [What ISIS practices,] it’s a different religion than we learned. It’s completely different, toughness in all aspects of life.”

Abu Usama and his brother were Shia, but he and his brother hid that from ISIS, as the group made clear that they intended to kill all Shia: “When we arrived and I heard them say, ‘We will kill you all. We will destroy you,’ I felt angry. I didn’t sit with them. My brother was convinced. He even changed the way he prayed. In front of them I said, ‘Yes, I already prayed.’ When I returned home, I prayed at home in the Shia way.” Abu Usama eventually fled the group.

Abu Yousef is an I8-year-old uneducated Syrian, an ISIS defector interviewed in Turkey. He recalls being recruited into ISIS from the Free Syrian Army and at first being enthusiastic about ISIS. However, he recalls how he became upset when ISIS trainers in his camp brought prisoners to be killed: “They were from Syria. They gave us knives to kill those slaves. They brought us 25 prisoners, and it was part of the training. First, I wanted to kill one of them. Then when I was about to do it, I realized I was killing someone, so I throw away the knife and ran away. They came after me, caught me, took my weapons and took me to the police station. And there were some like me that hesitated to kill the slaves. They shot at our legs with Kalashnikovs. They sent me to shariah camp again.”

During his re-indoctrination, Abu Yousef did not become convinced of ISIS’s righteousness. Moreover, ISIS did not give him a weapon again, as he was no longer trusted – something that led him to fear for his life. Likewise, he became even more disillusioned with ISIS’s cover-ups of their brutality on the local population: “That Tunisian fighter raped this 15-year-old kid inside the bath, when he went to wudu [Islamic cleansing before prayer].” Abu Yousef was shocked when the ISIS leaders realized there were witnesses and announced, “‘We are going to punish them,’ [but] they just covered it up and never punished them. The Tunisian was sent to Raqqa.” He continues, “But many others were doing this with women. I was hearing that they were raping women and then forcing them to marry them.” Abu Yousef became terrified he would be framed for an ISIS fighter’s crime since he was already marginalized and distrusted. “I felt very insecure. I was scared someone was going to blame me for something I didn’t do.” Abu Yousef defected from ISIS and fled to Turkey where he maintained his anti-ISIS views, despite others in the refugee camps trying to draw him back into rejoining the group.

Ibn Mesud, an I8-year-old Syrian interviewed in Turkey,[19] also recalls the ISIS leaders positively at first: “When they first came and talked about Islam, they were pretending that they were good. They took the young men to the camps. They told us that these people had robbed the country and don’t apply Allah’s laws. [They told us,] ‘We want you to join us to establish Allah’s laws, that the Islamic State is following the true Islam and when you go to join us in battle, if you die, you will go to Paradise.’ They talked about jihad, honor, what the Prophet said, may peace be upon him, that it is an obligation of Muslims to join jihad and things like that.”

His ISIS trainers tried to persuade the youth to take suicide missions, saying, “This will make you closer to paradise. This is a real opportunity.” Ibn Mesud had another view, however. “I thought that those who were immigrants, those who came from Egypt, for instance, should be the ‘martyrs,’ not us, the natives.” He remembers telling the ISIS leaders he had to care for his handicapped father, but they argued back, “‘We will take care of your family if you go [as a suicide bomber]. You won’t feel anything.’ He showed me an envelope and said, ‘You drink this stuff and then you won’t feel anything.’” Ibn Mesud noticed that when he showed doubts and the possibility of defecting from ISIS that they became negative toward him. “After I told them that I didn’t want to go on a ‘martyrdom’ mission, I felt that things really changed, that they were not treating me the same as when I first arrived.” Taking leave at home, he discussed ISIS’s pushing him toward suicide terrorism with his father and together they decided he should defect from ISIS and escape into Turkey.

Discussion

That ISIS prisoners, defectors and returnees may be undergoing a process of spontaneous deradicalization by virtue of experiencing disillusionment with the group and having time to reflect and deconstruct ISIS’s ideological claims is positive news and in our judgment it appears genuine, given the details provided by these men and women that support their reasons for deradicalizing. It also suggests that prisoners can do part of the rehabilitative work on their own and in some cases, contrary to the very real possibility of in-prison recruitment, radicalization and re-radicalization, prisoners may even support each other in deconstructing ISIS’s virulent ideology and unmasking their lies. While few prisoners in this sample moved all the way to a point of accepting full responsibility for their own actions and understanding that their actions made ISIS’s evil possible, many began to understand that they had been lied to, victimized and used by the group for purposes that did not align with their own needs or desires. Many became ashamed of their actions in the group and the fact that they had believed lies, but few moved all the way to remorse for their victims and a desire to make amends where possible. This latter lack of growth may be because the prisoners are still in dire straits themselves, in overcrowded and disease-ridden conditions where their focus is still more on themselves than their victims.

This article provides support for the theory of spontaneous deradicalization, that a significant portion of the deradicalization process can occur without a structured program in certain cases. Specifically, men and women who are less deeply entrenched in the terrorist ideology when they join and are motivated more so by higher-order personal needs than a desire to achieve the terrorist group’s purported goals are more likely to be disappointed and disillusioned by the group’s inability to fulfill their needs for belonging, significance, and meaning and then on their own begin to deradicalize.

Because ISIS recruiters are so skilled at promising potential recruits whatever they most deeply desire, those who were blinded by the idea of an Islamic utopia and who desired self-actualization, escape from problems or material gains rather than jihad are more likely to feel that ISIS misled them on purpose rather than feeling that ISIS as a group was mismanaged but that their cause remains noble. Ergo, as countries consider repatriating foreign fighters and their families from SDF territory, those individuals who have spontaneously deradicalized are very likely to be less dangerous and at a lower risk of attacking on native soil. However, these countries must nevertheless be prepared to provide adequate support for these returnees, whether or not they are prosecuted for their membership in or involvement with ISIS. As can be seen from the data presented in this article, spontaneously deradicalized men and women largely joined ISIS in the hopes of filling a void in their personal lives. They began to deradicalize on their own because ISIS failed to fill that void. Thus, they remain vulnerable to other antisocial groups and individuals who offer them the belonging and purpose they have yet to find. A comprehensive rehabilitation program for these individuals will require providing them with positive support and prosocial means for finding meaning in their lives and meeting the needs that have existed since before they joined ISIS.

ICSVE wants to give special thanks to the European Commission’s Civil Society Empowerment Programme’s Internal Security Fund and the Embassy of Qatar in the United States for supporting this project in part and for the Syrian Democratic Forces, Iraqi Falcons, Iraqi Counter Terrorism Services, Kenyan National Centre for Counter Terrorism, Albanian and Kosovar Justice Ministries and other American and European authorities and private citizens who helped the first researcher gain access to ISIS prisoners and returnees. All the Syrians interviewed in Turkey were interviewed with Dr. Ahmet Yayla.

Reference for this article: Speckhard, Anne and Ellenberg, Molly (August 3, 2020). Spontaneous Deradicalization and the Path to Repatriate Some ISIS Members. Homeland Security Today

About the authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D., is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 700 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past three years, she has interviewed 240 ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners as well as 16 al Shabaab cadres and their family members (n=25) as well as ideologues (n=2), studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS (and al Shabaab), as well as developing the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project materials from these interviews which includes over 175 short counter narrative videos of terrorists denouncing their groups as un-Islamic, corrupt and brutal which have been used in over 125 Facebook campaigns globally. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals on the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE both locally and internationally as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS and consulting foreign governments on issues of repatriation and rehabilitation of ISIS foreign fighters, wives and children. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, the EU Commission and EU Parliament, European and other foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA, and FBI and appeared on CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly writes a column for Homeland Security Today and speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhardWebsite: and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org

Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Molly Ellenberg, M.A. is a research fellow at ICSVE. Molly Ellenberg holds an M.A. in Forensic Psychology from The George Washington University and a B.S. in Psychology with a Specialization in Clinical Psychology from UC San Diego. At ICSVE, she is working on coding and analyzing the data from ICSVE’s qualitative research interviews of ISIS and al Shabaab terrorists, running Facebook campaigns to disrupt ISIS’s and al Shabaab’s online and face-to-face recruitment, and developing and giving trainings for use with the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos. Molly has presented original research at the International Summit on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma and UC San Diego Research Conferences. Her research has also been published in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, the Journal of Strategic Security, and the International Studies Journal. Her previous research experiences include positions at Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.