Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Militant groups such as the Islamic State (IS) and its…

The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers

by Asaad H. Almohammad, Ph.D. & Anne Speckhard, Ph.D.

Before deploying sources to collect information on the roles and functions of women in ISIS-held territories, a number of Syrian women rights activists were contacted. Approaching any topic that relates to violent jihadists and radicalization in Raqqa is often explained by the locals in terms of before and after ISIS takeover of the city. One of the activists, who worked in an organization that focused on women’s health, reported:

“Things were never great before the radicals’ takeover of the city, before the days of darkness. As a woman working on the prevention of domestic abuse and raising right-based awareness among women in rural areas, I was troubled by the culture of silence and unquestioned obedience created by shaming women at many fronts. Things weren’t always bad, we had our wins. We made some progress; like girls’ education in rural areas, weakening a culture of servitude, the use of contraceptives… Daesh did to men what many men did to women before. You would expect that from radicals. But to see women oppressing, abusing, and belittling other women at this scale, it feels like betrayal. It is so repulsive that I feel nauseous. You know they have an office for Daesh women? If somehow you forget yourself and speak loudly or take off your gloves, you should pray that if Daesh catches you that it is the Daesh men. You can beg the men, you can apologize, there is a chance that they would limit their abuse to verbal. Daesh women have no hearts.”

Indeed, in ICSVE interviews of Syrian ISIS defectors, including two women who served in the ISIS hisbah (Islamic police) we learned that women are the most brutal enforcers and take women who infringe on the dress and moral codes of ISIS to prison to flog and bite them. Women have actually bled to death after being bitten on their breasts and other fleshy parts with a metal “biting” device used for punishment.[1]

Women were among the earliest targets of ISIS. From slavery and sex trafficking to imposing strict Islamist rules and punishments preventing personal freedom and education, ISIS misogyny has been evident. While women to the largest extent are victims of ISIS atrocities, they also play significant roles in the terrorist organisation.[2] Without any reported combat presence, women’s role in online recruitment and the enforcement of ISIS Islamist rules and codes have been documented.[3] It is noteworthy that previous research argued that Islamist jihadi groups from conservative societies in which women do not play equal roles to men in working outside their homes often do not use women as suicide bombers or allow them to take combat roles until they get desperate.[4] Unlike Chechens groups who used women as bombers from the beginning, Palestinians and Iraqis jihadi groups abstained from using female bombers until it presented a clear advantage.[5] For example, when terrorist organizations’ leaders realized that male operatives became unsuccessful in passing through checkpoints while women could still hide bombs while breaching, they started using female bombers. To that effect, uncovered marriage certificate of ISIS’ brides[6] shows that both the husband and wife declare, ‘under conditions of wife,’ that:

If the Prince of believers [Baghdadi] consents to her carrying out a suicide mission, then her husband should not prohibit her.

It is safely argued that ISIS might be looking to use more female suicide bombers in the future. Eighteen year old, Diana Ramazova, the Russian national who carried out a suicide attack outside a police station in Istanbul’s historic Sultan Ahmet quarter in Istanbul after her husband was killed (while serving ISIS) is an instance of an ISIS female suicide bomber acting outside ISIS-held territories. Ramazova, converted after meeting Abu Aluevitsj Edelbijev, a Norwegian citizen of Chechen origin, in an online forum and later married and honeymooned with him for three months in Istanbul. The two then traveled in Turkey and entered Syria in July of 2014. Edelbijev is believed to have been killed fighting for ISIS in December of 2014. At that point two-months pregnant and a widow, Ramazova—illegally crossed back into Turkey—possibly sent by, or fleeing ISIS. Once inside Turkey, she made her way north to Istanbul by taxi where she stayed in a hotel until January 6, 2015, when she used two hand grenades to attack the Istanbul tourism police station.[7] Whether or not ISIS deployed her has still not been established and ISIS has never publically claimed the attack. However, she had enough money to take a taxi all the way from the Syrian border to Istanbul and to stay in a hotel once there. It’s possible that in her grief over her husband’s death, she volunteered for such a mission rather than marry another fighter. If she was operating under ISIS, she would have been one of the first ISIS-related female suicide bombers sent to attack outside of ISIS held territory.[8]

A limited number of research papers focused on ISIS’ success in attracting women to join its ranks[9] provided some insight into the role, albeit non-militant functions, the daily life of Western women, what ISIS promises them, and how it views women recruits. It is noteworthy that the cited research relied largely on social media and defector’s accounts in deducing its findings. To that end, the understanding of operations, functions, rank, directorate-based affiliation, and population of women in ISIS’ ranks is yet to be fully crystalized.

A previous report as well as defector interviews commented on the potential activation of an all-female death squad by ISIS.[10] That report relied on information obtained from former ISIS members and suggested that the group limited its recruitment of suicide bombers to local women. In the absence of intelligence information and due to the limited number of women who have successfully escaped ISIS strongholds, the role of women, including Western migrants, might have been misrepresented. As such, this endeavour attempts to clarify a number of different roles and functions of ISIS’ female members (both local and foreign).

To that end information obtained from trusted sources in ISIS strongholds was used to portray the entities that oversee female-based activities. The following figure demonstrates the divisions and subdivisions that run the women-based Kataib (battalions). It also details the types of operational duties for each battalion. That includes the enforcement of sharia laws, surveillance, combat, intelligence, assassination, and infiltration. Moreover, the geographical reach of each battalion is outlined. Additionally, details about multiple leading women in ISIS’ ranks are presented along with the type of training provided to their respective battalions. Last but not the least, the figure displays the origin of registered and trained female recruits and size of the battalions.

Figure One: The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives

Indoctrination, Recruitment and Registration

In June of 2013 ISIS declared Raqqa as its headquarters. At the same time ISIS was reported to engage in a wide campaign to appeal to the vulnerable populations in Raqqa taking charge of complaints filed by the public. It is noteworthy that at that time the city of Raqqa hosted a large number of internally displaced persons from other governorates[11]. At that time, Raqqa was one of the safest and most accommodating cities to people fleeing violence elsewhere in Syria. Syrians even referred to Raqqa as Hotel Revolution as it served a humanitarian function in hosting families affected by and escaping al-Assad’s regime atrocities. Some, both displaced and local civilians escaped the city before ISIS made it its capital; others didn’t have the means to flee to other Syrian cities or neighbouring Turkey, nor understood the importance of doing so. Arguably Raqqa was left with a large number of vulnerable people like orphans, widows, and the poor.

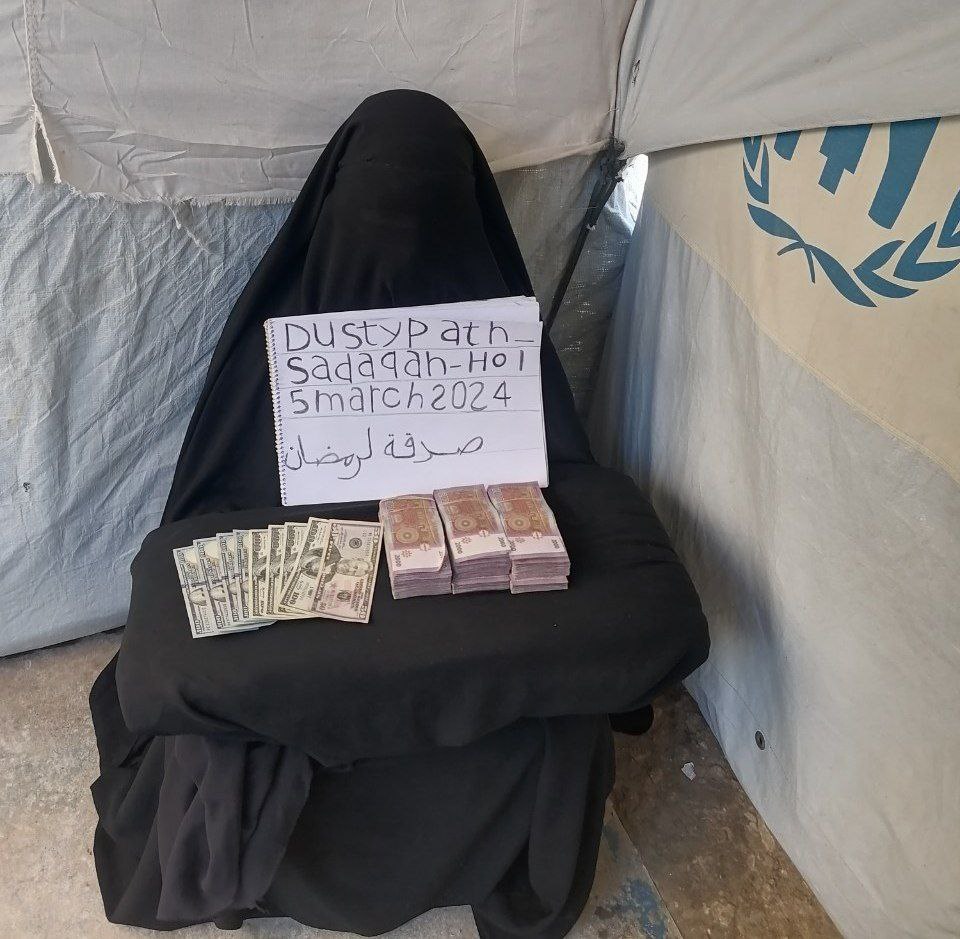

ISIS members, mostly males at the time, paid a significant effort to attract vulnerable populations to embrace its message and join its ranks offering them pay, food, propane allowances, stipends if their sons or husband’s were killed in battle, etc.. In early 2014, ISIS women also started to take part in that campaign. Along with their male companions, early female ISIS operatives made door-to-door visits to hand out food and money to poor residents and displaced persons and offering marriage to ISIS cadres to unmarried young women. These women also engaged in spreading ISIS’ ideology and raising awareness about the group’s Islamist rules and codes. In addition, they invited women to take sharia courses in the local mosques. A number of mosques were assigned the task of indoctrinating women and young girls. These mosques are namely, Al-Nūr, Imam Nawawi, and Umar Bin al-Khatab. The courses are now provided by ISIS women.

Another tactic ISIS used to get women to their indoctrination centers was via a policing force called the hisbah that used the carrot and stick approach with women who they deemed to have committed minor offences, such as wearing a face veil deemed too transparent, against their Islamist codes. The hisbah is group of male and female ISIS operatives, acting as the ISIS morality police, who intervene to coercively enforce the group’s doctrine through arresting, fining, detaining, and punishing individuals who are seen to stray from ISIS’ extreme Islamist rules. Women who get detained by the hisbah and are deemed to have committed minor offenses are fined 3,500 SYP on average. To ‘cleanse’ themselves from these sins they are forced to take a sharia course in one of the aforementioned indoctrination centees. According to interviews with defectors, including one woman who was herself a member of the hisbah, women who don’t get off so easily are taken to ISIS prisons where they are disrobed and flogged by hisbah women mercilessly on their bare skin. And if they are really unlucky, bitten with metal teeth on their fleshy parts so badly that some defectors have reported women bleeding to death as a result.[12]

The softer approach is often taken with young girls and women who are poor, single, divorced, or widowed who ISIS wishes to seduce into their ranks. They are not only exempted from paying the fine, but also get paid to participate in the course. It is documented that ISIS recruiters have a higher level of success recruiting women through the softer approach.

A Chechen woman by the alias Aum Imarah, who worked as a physician before immigrating to Raqqa, is reported to be a key recruiter. She is also the leader of a female-only battalion. Her rank and battalion will be discussed in a later section. Aum Imarah works with the women of the hisbah in overseeing recruitment programmes that target local Syrian women. She is reported to have recruited over 130 women to ISIS’ ranks. Given her nation of origin and heavy Arabic accent, that number is high.

Information obtained from trusted sources shows that ISIS has an office that handles the registration of women who wish to join its ranks. The office is located in an old Baathist youth centre in Raqqa, known as Hamida al-Tahir centre. The registration office encourages men coming from outside Raqqa governorate (foreigners and nationals) to register and recruit their wives and daughters into ISIS’s ranks as well. Females who are interested in security, intelligence, Internet recruiting or combat roles provide their details to the registration office. Each registered woman is given a recruitment number.

A woman known as Aum Kahtan is in charge of the female registration office. Aum Kahtan handles archiving all the information on female recruits. She in turn reports to six key female ISIS players. Sources have reported some details on the aliases of Aum Kahtan’s superiors:

- Aum Mariam: Reportedly, a French national. She is reported to be the leader of al-Khansa battalion.

- Aum Hiba: Reportedly, a French national believed to be Hayat Boumeddiene, France’s most wanted woman. She fled France after her husband killed a trainee police officer. Now she handles the training of new recruits. She is reported to have participated in training female Emni (ISIS security forces) [13] operatives and Western ISIS women who are affiliated with battalions that function under other divisions (not the Emni). Her trainees are reported to wear a uniform that resembles the one she wore in the following picture.

- Aum Muhammad: Reportedly a Tunisian national who was born with the name Subhiah.

- Aum Fatima: Reportedly a Swedish national who was born with the name Lisan.

- Aum Ibrahim: Reportedly a Tunisian national.

- Aum Abdullah: Reportedly a Tunisian national.

As of mid-April 2017 ICSVE obtained data shows the registration office listed at least 800 trained females who are affiliated with three women-only battalions, namely, Khadija Bintu Kwaild, Aumahat al-Moaminin, and al-Khansa. These battalions, as demonstrated in the infographic, are affiliated with different ISIS entities. Moreover, al-Muhajirin Directorate was reported to oversee an elite women-only battalion known as al-Zarqawi Battalion. The obtained data indicates that battalion has no less than 480 trained recruits. That said, our investigation also uncovered a relatively new battalion known as Bintu al-Azwar Battalion. To that end, the appropriate point of departure is made through presenting the first all-female entity within ISIS; that entity is al-Dawa battalion. Its significance lies in having established two prominent all-female entities and setting the ground work for women’s indoctrination, recruitment and training in ISIS as morality police, operatives, spies, infiltrators, assassins and in combat roles.

Al-Dawa Battalion

As mentioned earlier this battalion is the first all-female entity within ISIS. Members of this battalion took some basic sharia courses but were not trained to use weapons. In the early months of ISIS’ takeover of Raqqa, sometime after June 2013, this all-female group was formed. At the time, Aum Luay, a Syrian national from Raqqa, emerged as its first commander. The group, now disbanded, had a wide range of activities, especially before the closure of public schools in Raqqa. They helped to spread ISIS’ message through a campaign of door-to-door and schools visits. Members of al-Dawa handed out food, clothes, and money to those in need.

During that time, al-Dawa was not viewed so negatively by the locals, as the calculated moves of ISIS leadership to care for families affected by the conflict, particularly, orphans, widows, and the poor their desired effects among the local population. Al-Dawa operated under the protection of a Tunisian man known as Abu Mujahid. The group enjoyed the support of ISIS’ leadership and cultivated support among the female local population in Raqqa (both residents and displaced persons).

It was later that al-Dawa started to promote female training for policing under the hisbah, security, and combat roles. It is noteworthy that members of al-Dawa lacked know-how regarding the use of arms. Abu Mujahid was tasked with the arrangements required for the training of al-Dawa members and new recruits. The battalion, however started to lose its popularity among local women when it began taking the lead in the enforcement of ISIS’ dress code. That shift was largely noticed when the battalion led a campaign against women wearing high heels. During that time women who were seen wearing that style shoe were physically and verbally abused by members of al-Dawa. On one occasion they arrested a woman for not abiding by ISIS’ dress code and flogged her 23 times. Henceforth al-Dawa became a feared entity in Raqqa.

The majority of al-Dawa’s operatives were Syrians. That group was originally made up of 39 women. The group’s base was one of the earliest targets of the American-led campaign; it was attacked on the 29th of October 2014, killing 32 members of al-Dawa. Before the attack the battalion helped to establish two other battalions, al-Khansa and Aumahat al-Moaminin. These two groups are still operational, but the remaining al-Dawa members disbanded after the attack. Despite its demise, al –Dawa Battalion set the ground work for future all-female entities serving ISIS. With the knowledge that ISIS gained from forming and running its first all-female battalion, its leadership managed to cultivate more support and recruitment among young girls and women in its declared capital of Raqqa. The next generation of female ISIS members have been better trained in a much wider variety of roles, better organized, and move involved in the broader organization.

Al-Khansa Battalion

Al-Khansa is one of the two battalions that emerged from and succeeded al-Dawa. The current commander of the all-female group is known as Aum Mariam al-Faransi. She is a French national of Tunisian descent. She was brought from Mosul, Iraq and entrusted by ISIS’ directorate of fighters to lead the battalion. She is the wife of a key figure in that directorate and reports to him. The first leader of the group was born as Rahaf al-Madhun, a Syrian woman from al-Sukhnah, Homs. She was succeeded by a woman known as Aum Ahmad, who was born as Ibtisam al-Fahal. According to our sources, as well as defector interviews, Aum Ahmad used to own and run a brothel in the city of Raqqa before she “rehabilitated” herself under ISIS rule.[14] Before 2011, she had connections in the Syrian intelligence and army. She also worked as a fixer. Locals would pay her to bribe Syrian officials to resolve issues related to businesses or detained individuals. Sources reported that Aum Ahmad became very conservative before ISIS’ takeover of Raqqa. Moreover, she was killed, though it is unclear how, when, and by whom exactly. Aum Mariam al-Faransi is the third and current commander of al-Khansa.

The majority of al-Khansa battalion are foreign women from Europe. Among the European women, the majority speak French. The group also has members from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Of the members from MENA, Tunisians are the largest portion. A small number of Syrian and Iraqi women are also reported to be affiliated with al-Khansa.

Members of al-Khansa battalion are given military and intelligence training. They are armed with Kalashnikov rifles and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). They are also trained to assemble and make gun noise suppressors from basic materials. Recruits of this battalion are taught surveillance methods and how to carry out assassinations. This battalion’s main training camp is in a local institute in Raqqa, just opposite al-Fardus Bakery. The institute is called al-Khansa school. A woman who matches the description of Hayat Boumeddiene has been seen going in and out of that institute. Sources’ reports seem to confirm obtained data that indicates Boumeddiene’s trainees wear a brown uniform.

Al-Khansa battalion has been documented to conduct surveillance operations within ISIS’ strongholds. As the commander of the battalion, Aum Mariam oversees the operation of al-Kansa under the direction of ISIS’ directorate of fighters. She receives orders and reports to that directorate through her husband. The surveillance targets of this all-female group are those ISIS’ directorate of fighters deemed suspicious, be it women, men, journalists, rival fighters, or other ISIS members.

Recently members of al Khansa battalion have been seen armed in the city of Raqqa. This might be an indication of an increasing threat or that they might have been activated to carry out combat missions. European members of al-Khansa who have been weapons trained and ideologically indoctrinated pose a significant threat if they manage to return to their countries of origin, particularly as many Western countries give light sentences or no sentence at all to women returning from ISIS, assuming they were coerced or naively followed their husbands into the terrorist organization. This has indeed created a conundrum in some Western countries where women plead ignorance and innocence upon their return and there is little evidence with which to convict them[15] other than travel to Syria, or their fighter husband’s get convicted and they are allowed to live freely.[16] Some of al-Khansa’s recruits have received years of intense training on the use of arms and assassinations and are highly ideologically indoctrinated. Their potential involvement in violent activities in Europe could be devastating. To that end it is important to mention that, based on information obtained from trusted sources, al-Khansa’s surveillance operations in Syria have resulted in the killing of a number journalists and activists.

Aumahat al-Moaminin Battalion

Aumahat al-Moaminin Battalion is the other battalion, besides al-Khansa, that emerged from and succeeded al-Dawa. The battalion’s office is located in Zahrat al-Furat Hotel in Raqqa, located above 23 Shibat Bakery. That office is within a center of the hisbah. An Iraqi woman was reported to be the commander of this group. She is known as Aum Jafar. Her second in command is another Iraqi woman who goes by the alias Aum Zaid.

This battalion is trained in the use of arms namely, rifles and handguns. Its members are also trained to carry out defensive combat roles. However, this battalion has not yet been activated to participate in combat. Instead, it operates under the leadership of the hisbah’s committee and functions as its all-female arm. Its members are deployed to the streets to enforce, arrest, and inform on local civilians who are not abiding by ISIS’ moral codes. While the entity’s operations largely target and enforce penalties and punishments upon female populations in ISIS-held territories, they have also been reported to inform on male civilians.

Members of this battalion are heavily engaged in the indoctrination and recruitment activities of both female and male individuals living in ISIS’ strongholds. They are generally accompanied on their patrols by male members of the hisbah. The male operatives provide this all-female group with protection and carry out arrests of male civilians under the request of members of this battalion. A large number of Syrian women report to the leadership of the battalion. The second largest portion of this entity is Iraqi women. Defectors, particularly Syrians who sometimes do not distinguish clearly between these two groups (al-Khansa and Aumahat al-Moaminin) report that all European women are invited to join the ISIS hisbah (what they generally call these two groups) and are given a Kalishnikov and answer to almost no one.[17] This group’s key potential threat rests in its surveillance expertise. Their combat training could raise another threat if ISIS chooses to activate them as a defensive force.

Amaliat Khasa (Special Operations)/Khadija Bintu Kwaild Battalion

This all-female battalion is by far the most active and lethal. Its members are highly trained, especially in carrying out assassinations outside ISIS-held territories. They wear explosive vests and are skilled in assembling sticky bombs, the use of handguns, Kalashnikov rifles, and RPGs. The sharia courses this battalion receive are the most intense, compared to other female-based entities. The training of this battalion is provided by the Emni. Moreover, a woman who matches the description of Hayat Boumeddiene is reported to be on the trainers’ team. Under certain circumstances, operatives of this battalion are exempted from abiding by ISIS’ dress code.

Moreover, members of this all-female battalion receive infiltration tactics training. Operatives of this entity are sometimes referred to as Anghmasiat (women who infiltrate enemy lines). To that end, it is noteworthy that the ISIS’ Emni has since its inception used infiltration units to weaken or defeat rival forces.[18] Operatives on infiltration missions might advance undetected or remain behind to inflect maximum damage, as major forces retreat. Other tactics that ISIS’ Emni uses are the activation of sleeper cells and the use of spies to carry out attacks within rival territories. Along with assassinations, this all-female battalion is reported to be skilled in assembling explosive belts and devices.

After receiving training and taking ISIS’s sharia courses, members of this battalion are deployed to the city of Raqqa. It is reported that every three newly deployed members are paired with one to two senior operatives. Teams of four or five patrol the city for a few weeks before they receive local missions. Missions can include luring wanted males to particular places before arresting or executing them. For ensnaring males from big local tribes, the aforementioned teams were reported to instigate incidents to justify apprehending such targets. On one reported occasion, one of the teams failed in luring a male target. An operative of the team screamed, claiming that the male target assaulted her. Male members of the hisbah rushed to apprehend the man. The all-female teams often partner with male teams from the hisbah.

After finishing the patrolling phase, recruits get promoted to permanent positions within the battalion. The battalion functions under the leadership of the Special Operations office. That office is an executive branch of the Emni.[19]. It is reported that the Special Operations office managed to send some members from this battalion to a number of hot zones in Syria. Female operatives are reported to have been sent to Lebanon, Turkey, and Western Europe.

Under the Emni’s leadership, this battalion handles interrogating female detainees in Emni prisons. That includes western and local detainees. Members of this battalion are reported to be trained to use torture and their use of this interrogation method on detainees is documented. The population of female detainees includes kidnapped western and local women. The detainees could be accused of conspiring against ISIS, hostages who are detained for ransom, and spouses, daughters, mothers, and sisters of men wanted by the Emni.

The Khadija Bintu Kwaild battalion is notably active and present across Raqqa, Mayadin, Tabqa, Bu Kmal, and Mosul. The entity is reportedly led by a Syrian woman from the city of Aleppo who is known as Aum Ali. She was born as Swad al-Ahmad. The battalion has been active in carrying out special operations. Along with spying and assassinations, the battalion hunts ISIS’ enemies across ISIS’ strongholds and abroad. They are also entrusted with interrogating male targets outside ISIS’ strongholds. It is reported that they have led a number of successful operations against affiliates of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in Aleppo and in Qamishli, against Kurdish and Arab targets.

Furthermore, they are also tasked with spying on suspected ISIS members. This entity is heavily involved in gathering intelligence outside ISIS held territories in Syria, Iraq, and neighbouring countries. They are trained to assassinate ISIS’ enemies within the group’s stronghold and abroad. A number of trusted sources confirmed that this all-female battalion reports intelligence and carries out operations under the direction of the ISIS Emni. Moreover, this entity was reported to take part in operations abroad.

As of early October 2015, sources reported that a female member of this battalion and a male Emni operative travelled to Sanliurfa, Turkey on a mission to assassinate Ibrahim Abd al-Qader a member of the grassroots anti-ISIS monitoring organization known as Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently and his friend, Fares Hammadi.[20] . The male Emni operative was reported to be Tilas Sruur (see the photo below), a Syrian national from Raqqa. The identity of the female operative is unknown.

Tilas Sruur

After arriving to Turkey, the male Emni operative befriended and earned the trust of the activists. Then, he introduced them to his female co-operative who sources reported added sedatives to the their drinks while visiting them at their home. The male operative joined his female partner after the two men lost consciousness. Sources added that each of the operatives assassinated one of the activists by slitting their throats and nearly beheading them. In the months following the assassination social media accounts accused the male Emni operative of the assassination of Abd al-Qader. As of early December 2015, a picture of the male Emni member was posted online by one of the victims brothers, accusing Sruur of killing al-Qader (see the picture of the post below). Sruur was also reported to be proud for his role in the mission. He has informed a number of individuals that he was one of the assassins. It is believed that the near beheading of Fares Hammadi was handled by the female operative. Sources added that the two operatives reported to an Emni cell in Turkey.

Circled: Ahmad al-Qader accusing Sruur of the killing of his brother.

On another key operation, a member of this all-female battalion was reported to have carried out an effective mission. A former member of ISIS, with knowledge of key ISIS operations and figures, escaped to Damascus. The Emni’s special operations office assigned a female member of the battalion with the task of apprehending the deserter, and either bringing him back to the city of Raqqa or assassinating him. The operative managed to apprehend the target and bring him back to Raqqa. The journey from Damascus to Raqqa is long, with many areas controlled by the Syrian regime, FSA affiliates, and other Islamists groups undoubtedly crossed. The man was reported to have many bruises on his face by the time the female operative delivered him to the Wali’s (governor’s) office. He also was reported to be disoriented, which suggests that he might have been drugged. The man was dragged and humiliated in public before being taken to a detention centre in Tabqa. He was then interrogated by male operatives of the Emni and executed.

While the majority of Khadija Bintu Kwaild battalion are Syrian and Iraqis, Western European women make up a significant minority within the ranks of this all-female entity. It is reported that Syrian and Iraqi women take the lead on operations that are carried out in Syria and Iraq. The ranks and operations of Western European operatives in this brigade are still unclear. It is suspected that they would be more effective in carrying missions on behalf of ISIS outside MENA as they may pass security more easily as appearing less of a threat than their male or even middle eastern female counterparts. Whether Western European operatives are active in Europe or elsewhere is unknown.

Al-Zarqawi Battalions

This entity includes female and minors (males only). While the majority of the female members of units affiliated with al-Zarqawi Battalions are Europeans (Central Asian, Balkans, and Western), local Syrian and Iraqi women are also reported as affiliated with the battalions. Some of the local women are married to European members of ISIS. The female al-Zarqawi Battalion is led by a Chechen woman who is a trained physician. She is known by the alias Aum Imarah. Female members of the battalion are recruited and operate under the leadership of the Directorate of the Muhajirin (immigrants/foreign fighters). It is noteworthy that their training is handled by the Special Operations office of the Emni.

The directorate of the Muhajirin (immigrants/foreign fighters) is led by a Chechen man who is known as Abu Omar al-Shishani. The directorate oversees social, economic, and legal affairs that relate to foreign members of ISIS. That said, Aum Imarah, the commander of the all-female arm of al-Zarqawi Battalions, reports to al-Shishani, who in turns report to the Emni director in Syria regarding the operations of the all-female entity.

The all-female al-Zarqawi group is reported to be made of at least 480 female members. Members of this entity receive training similar to that of Khadija Bintu Kwaild battalion. The lion’s share of the training is in the assembly and use of noise suppressors and explosive devices (particularly sticky bombs). Female recruits of al-Zarqawi battalions are often seen in public carrying handguns and rifles. As of mid-April 2017, they started wearing explosive vests. They are also reported to approach local women and their male companions to persuade them to join ISIS.

Moreover, obtained information indicates that female members of al-Zarqawi battalions receive frequent training from Bintu Kwaild battalion. That training includes methods and tactics of infiltration. Members of this entity are expected to participate in joint operations in the future, under the leadership of the Emni’s Special Operations office and the directorate of the Muhajirin. Details on the planned operations were not obtained. Given the national make up (mostly European) of female operatives, European cities might be the target of such operations. While there is no documented field experience among members of this entity, their intensive training might pose a threat and as noted earlier, European and Balkan countries often do not imprison wives of ISIS foreign fighters who manage to return home not expecting them to be much a security threat.[21]

Bintu al-Azwar Battalion

This all-female group is relatively new. A number of sources reported that they first became aware of the battalion’s name during November 2016. This entity is reported to be led by a Palestinian woman who is known as Aum Mwath al-Makdisi. The group recruits both offline and online. Their online recruitment targets are young Sunni Muslim women, widows and divorcees from Turkey, Tunisia, France, Belgium, and the UK. Offline, the battalion promotes itself as a sharia course that is devoted to the teachings of Islam. Additionally, meals and financial assistance are promised to those who participate in the promoted sharia course. The offline recruitment activities were documented in Raqqa, Syria and its outskirts.

Initially, the courses are given in houses of the women who sign up for it. Slowly, the course begins to delve into extreme narratives and justification, similar to those preached by ISIS’ religious figures and spokesmen. Throughout the course, some women get excluded. Only those susceptible to ISIS’ message are retained. After finalizing the sharia course, the remaining women are offered military training. It is noteworthy that foreign women were reported to have taken the course on one occasion.

After taking the sharia course, interested and selected women start their training. The mission behind the training is to equip the women with the skills required to carry out infiltration operations, assassinations, and suicide attacks. Moreover, the recruits are trained how to use handguns, rifles, RPGs, knives, and explosive vests, to hide in civilian populations, and to install and remove explosive devices (especially sticky bombs). A large part of the training is devoted to the installation of explosive devices on targets’ vehicles and how and when to remove them if the target doesn’t show up or in the case of malfunction.

While the recruitment activities of this battalion are notably active, the division that oversees its operations is still unknown. This all-female entity might pose a threat to the American forces and their Syrian allies if its’ operatives are activated. Their training could allow them to cause serious damages on the forces attempting to liberate Raqqa and beyond.

Conclusion

Previous reports and research on females in ISIS have documented their role in recruiting both men and women online. Two offline functions, namely, their role within the hisbah and in carrying suicidal terrorist attacks were observed and reported by commentators. Using information obtained from trusted sources in ISIS held territories and neighbouring countries; this report endeavoured to determine and disambiguate the offline roles of women affiliated with the terrorist organisation.

To that effect, this report uncovered a number of aspects related to the organizational role of women within ISIS. Throughout this research, the evolution of such roles was observed. Early women recruits were found instrumental in spreading ISIS’ message and increasing local recruitment from vulnerable populations with the city of Raqqa. Women within the organization were associated with caring for the most vulnerable. ISIS might have intended to capitalize on the positive attitude towards women who pioneered the enhancement of their brand image by creating the first all-female entity (i.e., al-Dawa battalion). As members of the first all-female group started to operate as the female-based arm of the hisbah to enforce ISIS’ strict Islamist rules, the popularity of female operatives began to decline. At that time ISIS recognized the additional offline function of women in increasing local recruitment. They also saw an opportunity in training women to occupy other functions including spying, infiltration, carrying out assassinations and covert attacks.

The establishment of al-Khansa and Aumhat al-Moaminin battalions marked an advancement in ISIS’ learning curve. As discussed earlier, the later all-female entities were more professional and task specific. Through Aumhat al-Moaminin, the group empowered their female members to engage in surveillance operations and to enforce its strict Islamist codes among the local population. Giving its theological role, the entity capitalized on spreading the ISIS brand of Islamic teachings in increasing female recruitment. ISIS arguably realised the vital functions and operations (i.e., enforcement, surveillance, assassination and infiltration) women could play in the organization, particularly if it loses its territory and is driven into underground guerrilla and terrorist operations. ISIS’ Emni allocated resources to get women to occupy such roles through al-Khansa battalion.

ISIS seems to use the experience gained from running al-Khansa battalion to train and prepare female European operatives and recruits from MENA. Women in al-Zarqawi battalion, mostly European, are given notably intense training that resembles the one of al-Khansa. It is hard to imagine that ISIS would activate European operatives within the MENA giving their often reported poor Arabic linguistic skills. It is plausible that the ISIS’s Emni might intend to use them to target European targets in the future—particularly given that women returning to the West from ISIS often receive light or no sentences. It is also documented that since late months of 2016, ISIS has been heavily involved in recruiting local women.

Moreover, this report detailed the ranks and departmental affiliation of women within ISIS. Obtained information indicates that four divisions oversee the operation of all-female entities. These divisions are, Emni, the hisbah committee, fighters’ directorate, and al-Muhajirin’s Directorate. Notably, the most active all-female group is the one operating under the leadership of the Emni’s special operation office. The Emni is also one of the most active divisions in ISIS.

The training, geographical deployment, and armament of the discussed all-female groups are demonstrated. Having that knowledge helps to paint a clearer picture of women’s organizational capabilities within ISIS. ISIS does not seem desperate to activate all of its female operatives. Moreover, as they are hemmed in by opposing forces, the group might begin to feel the need to use its female recruits in combat roles, something it has up to now shied away from. Historical accounts on terrorist organisations suggest that groups like ISIS often, when desperate enough, activate female operatives to take on combat roles and suicide missions [[22]]. It should also be mentioned that the demonstrated capabilities of female recruits should not be underestimated. This report uncovered that females in the ranks of ISIS are capable of handling extreme missions and are able to inflict substantial damage.

Reference for this Article: Almohammad, Assad & Speckhard, Anne (April 22, 2017) The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers. ICSVE Research Reports.

About the Authors:

Asaad H. Almohammad, Ph.D. is a Syrian research fellow and novelist. He completed his Doctorate in Political Psychology and Marketing. His academic work addressed how psychopolitical factors alter implicit and explicit emotional responses and to what levels these responses are predictive of political behavior. He has also spent several years coordinating and working on projects across ISIS-held territories. To date making use of a network of on the ground contacts, he has addressed a number of financial, operational, and militant activities of the terrorist organization. He is also interested in political branding, campaigns and propaganda, post-conflict reconciliation, and deradicalization. In his spare time Asaad closely follows political affairs, especially humanitarian crises and electoral campaigns. He is especially interested in immigration issues.

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D. is Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University in the School of Medicine and Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) where she heads the Breaking the ISIS Brand—ISIS Defectors Interviews Project. She is the author of: Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS and coauthor of ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate; Undercover Jihadi; and Warrior Princess. Dr. Speckhard has interviewed nearly 500 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including Gaza, West Bank, Chechnya, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey and many countries in Europe. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism experts and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA and FBI and CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhardWebsite: https://www.icsve.org

[1] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. And Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118.

[2] Speckhard, A. ( Dec/January 2016 ) “Brides of ISIS: The Internet seduction of Western females into ISIS.” Homeland Security Today 13, 38-40. ; Anne Speckhard (March 8, 2017) Women’s Roles in Terrorism and Women Fighting Back, ICSVE Brief Reports.

[3] Speckhard, A. ( Dec/January 2016 ) “Brides of ISIS: The Internet seduction of Western females into ISIS.” Homeland Security Today 13, 38-40. Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. andSpeckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118.

[4] Anne Speckhard (2008) The Emergence of Female Suicide Terrorists, , Conflict and Terrorism , Volume 31:1-29. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/8620947/The_Emergence_of_Female_Suicide_Terrorists

[5] Speckhard, A. (2008). “The Emergence of Female Suicide Terrorists.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 31: 1-29. Anne Speckhard (2009). Female suicide bombers in Iraq. Democracy and Security, 5(1), 19-50. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/10301179/Female_Suicide_Bombers_in_Iraq; Speckhard, A. and K. Akhmedova (2006). Black Widows: The Chechen Female Suicide Terrorists. Female Suicide Terrorists. Y. Schweitzer. Tel Aviv, Jaffe Center Publication.; Speckhard, A. and K. Akhmedova (2008). Black Widows and Beyond: Understanding the Motivations and Life Trajectories of Chechen Female Terrorists. Female Terrorism and Militancy: Agency, Utility and Organization: Agency, Utility and Organization C. Ness, Routledge. Speckhard, A. (May 4, 2015) “Female terrorists in ISIS, al Qaeda and 21rst century terrorism.” Trends Research.; Speckhard, A. ( Dec/January 2016 ) “Brides of ISIS: The Internet seduction of Western females into ISIS.” Homeland Security Today 13, 38-40.

[6] Speckhard, A. ( Dec/January 2016 ) “Brides of ISIS: The Internet seduction of Western females into ISIS.” Homeland Security Today 13, 38-40.

[7] Letsch, C. (January 16, 2015). Pregnant Istanbul suicide bomber was Russian citizen. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/ jan/16/pregnant-istanbul-suicide-bomber-russian-citizen Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/16/pregnant-istanbul-suicide-bomber-russian-citizen

[8] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC.

[9] Louisa Tarras-Wahlberg (January 9, 2017) Seven Promises of ISIS to its Female Recruits, ICSVE Research Reports.; Hoyle, C., Bradford, A. & Frenett, R. (2015). Becoming Mulan? Female Western Migrants to ISIS, Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Retrieved from http://www.strategicdialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/ISDJ2969_Becoming_Mulan_01.15_WEB.pdf; Saltman, E. and Smith, M. (2015). ’Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’ Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon, Institute for Strategic Dialogue. Retrieved from http://www.strategicdialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Till_Martyrdom_Do_Us_Part_Gender_and_the_ISIS_Phenomenon.pdf; Rafiq, H. and Malik, N. (2015). Caliphettes: Women and the Appeal of Islamic State, Quilliam Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.quilliamfoundation.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/publications/free/caliphettes-women-and-the-appeal-of-is.pdf; Speckhard, A. ( Dec/January 2016 ) “Brides of ISIS: The Internet seduction of Western females into ISIS.” Homeland Security Today 13, 38-40. Speckhard, A. and Yayla, A. S. (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate.

[10] Speckhard, A. (October 28, 2015). Anne Speckhard (October 28, 2015) ISIS readying to activate an “all female suicide brigade”? . ICSVE Brief Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/brief-reports/isis-readying-to-activate-an-all-female-suicide-brigade/ Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC.

[11] David Remnick (November 22, 2015) Telling the truth about ISIS and Raqqa, The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/telling-the-truth-about-isis-and-raqqa

[12] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. andSpeckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118.

[13] Almohammad, A., & Speckhard, A. A., 2017) (April 12, 2017). Abu Luqman – Father of the ISIS Emni: Its Organizational Structure, Current Leadership and Clues to its Inner Workings in Syria & Iraq. ICSVE Research Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/abu-luqman-father-of-the-isis-emni-its-organizational-structure-current-leadership-and-clues-to-its-inner-workings-in-syria-iraq/

[14] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. andSpeckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118.

[15] ARANEWS (November 2, 2016). Returning Dutch Jihadi bride under investigation for planning attacks in Holland. Retrieved from http://aranews.net/2016/11/returning-dutch-jihadi-bride-investigation-planning-attacks-holland/

[16] Speckhard, A., & Shajkovci, A. (April 14, 2017). Drivers of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo: Women’s Roles in Supporting, Preventing & Fighting Violent Extremism. ICSVE Research Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/drivers-of-radicalization-and-violent-extremism-in-kosovo-womens-roles-in-supporting-preventing-fighting-violent-extremism/

[17] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. andSpeckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118.

[18] Speckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (2016). ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate, Advances Press, LLC. andSpeckhard, A. and A. S. Yayla (December 2015) “Eyewitness accounts from recent defectors from Islamic State: Why they joined, what they saw, why they quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, 95-118. Almohammad, A., & Speckhard, A. A., 2017) (April 12, 2017).; Abu Luqman – Father of the ISIS Emni: Its Organizational Structure, Current Leadership and Clues to its Inner Workings in Syria & Iraq. ICSVE Research Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/abu-luqman-father-of-the-isis-emni-its-organizational-structure-current-leadership-and-clues-to-its-inner-workings-in-syria-iraq/

[19] Abu Luqman – Father of the ISIS Emni: Its Organizational Structure, Current Leadership and Clues to its Inner Workings in Syria & Iraq. ICSVE Research Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/abu-luqman-father-of-the-isis-emni-its-organizational-structure-current-leadership-and-clues-to-its-inner-workings-in-syria-iraq/

[20] Speckhard, A., & Yayla, A. (October 30, 2015). The Long Arm of ISIS. ICSVE Brief Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/brief-reports/the-long-arm-of-isis-two-activist-journalists-beheaded-inside-turkey/

[21] Speckhard, A., & Shajkovci, A. (April 14, 2017). Drivers of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo: Women’s Roles in Supporting, Preventing & Fighting Violent Extremism. ICSVE Research Reports. Retrieved from https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/drivers-of-radicalization-and-violent-extremism-in-kosovo-womens-roles-in-supporting-preventing-fighting-violent-extremism/

[22] Anne Speckhard (2015). Female Terrorists in ISIS, al Qaeda and 21rst Century Terrorism. Trends Research & Advisory Blog.[Elektronisk] http://trendsinstitution. org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/05/Female-Terrorists-in-ISIS-al-Qaeda-and-21rst-Century-Terrorism-Dr.-Anne-Speckhard11. pdf Hämtdatum:[2015-12-22].